Match Made: After a Long Engagement, Japan and India Tie the Knot

CONTENTS

- India-Japan Relationship

- Tokyo’s 10-year Courtship of Delhi Rewarded

- ODA at Heart of Japan’s India Strategy

- Japan FDI inflows modest, but picking up

- Potholes, Power Cuts and Paperwork

- Boom Times Set to Continue

- Panasonic: Doing Business in India “Not a Piece of Cake”

- Investment Areas Diversifying

- Ranbaxy Sees Potential in Rural Market

- Doing Business in India Challenging for SMEs

- India Has Long To-Do List

- Prospects Bright for Future Cooperation

India-Japan Relationship

BANGALORE—It’s a marriage made in heaven: The bride brings to the altar the world’s fastest-growing middle class—young, well educated and with money to spend—and the groom the world’s most advanced manufacturing technology and billions of dollars worth of soft loans to fund badly needed infrastructure projects.

India and Japan need each other. Their trade and investment relationship, cemented recently with the conclusion of the landmark Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), has the potential to be an extremely fruitful one if the two sides can work at their marriage and overcome sources of friction.

For Japan, whose workforce is shrinking rapidly due to its having one of the fastest-aging populations in the world and a chronically low birthrate—factors that have helped depress domestic demand—it has long been a matter of urgency to find new markets and manufacturing bases abroad. India, with its technological expertise, enormous population, whose average age is 25, against Japan’s 45, and low labor costs, makes an attractive partner.

The CEPA is the latest in a string of political initiatives undertaken in the past decade aimed at strengthening economic ties between India, the world’s biggest democracy, and Japan, Asia’s oldest democracy. So can Japanese firms in India expect to live happily ever after?

Tokyo’s 10-year Courtship of Delhi Rewarded

In a visit to India’s information technology hub, Bangalore, on Aug. 23, 2000, former Japanese Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori proposed the Japan-India IT Promotion and Cooperation Initiative, a plan that was quickly implemented. The following day in New Delhi, Mori and then Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee endorsed another Japanese plan, the Global Partnership between Japan and India in the 21st Century, which called for cooperation in the areas of security, disarmament and proliferation as well as strengthened cooperation in economic fields.

Following Mori’s visit—the first by a Japanese premier in 10 years—reciprocal visits of the countries’ top leaders took place annually. Bilateral relations were elevated to a new level in December 2006 with the signing in Tokyo of the India-Japan Strategic and Global Partnership accord by visiting Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh and then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. That agreement, which the joint statement announcing it said was designed “to impart stronger political, economic and strategic dimensions to bilateral relations,” served as the framework for the four-year negotiations toward the CEPA, under which tariffs will be removed on almost 90 percent of Japan’s exports to India and 97 percent of India’s exports to Japan.

During his visit to India in December, 2009, then Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama set a goal for lifting the value of bilateral trade to $20 billion within a year from the $13 billion logged in 2008-09 and offered Japanese nuclear technology to India. Japan and India began negotiations on civil nuclear energy cooperation in June, and the discussions are at an advanced stage.

ODA at Heart of Japan’s India Strategy

Japanese official development assistance to India, meanwhile, has been a pillar of the bilateral economic relationship for half a century. Since 1958, Japan has extended ODA totaling ¥3.4 trillion to India, which has been Japan’s biggest ODA recipient for seven consecutive years since fiscal 2003. In fiscal 2009, Japan’s ODA loans to India were worth ¥218 billion ($2.58 billion).

According to a Japanese Foreign Ministry outline of Japan’s ODA to India, the purpose of such assistance is to foster sustainable growth in the country, which it believes will underpin such growth in Asia as a whole, and to help create a favorable investment climate. Targets of ODA are infrastructure projects in fields including transportation, energy, water supply and sewage and irrigation systems.

Recent flagship projects include the Delhi Metro rapid transit system and metro projects in Kolkata, Bangalore and Chennai, and the Dedicated Freight Corridor project between Delhi and Mumbai, which is designed to transform India’s freight logistics. In the pipeline is a plan for Japan to assist in the construction of 24 green cities in the envisaged Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC). Spanning six states, the DMIC is the most ambitious infrastructure project India has launched with Japan, a world leader in eco-friendly technologies, and is expected to cost up to $90 billion.

Japan FDI inflows modest, but picking up

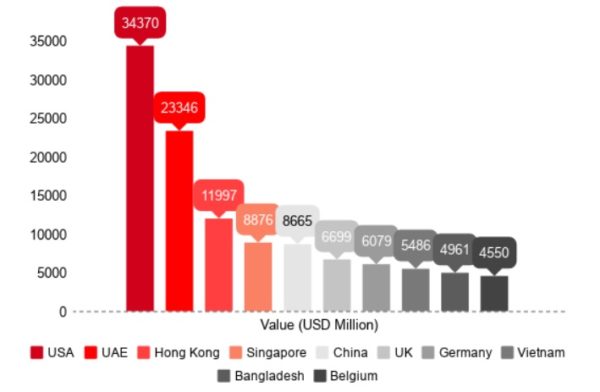

Foreign direct investment by Japan in India has been extremely modest in comparison with Japanese investment elsewhere in Asia, notably China, but has shown signs of picking up steam recently, though moving in fits and starts—India FDI inflows from Japan were worth $400 million in 2002-03, but hovered between a quarter and half that level over the next four years before spiking to $800 million in 2007-08 then plunging to $200 million in 2008-09. Foreign technology transfer approvals are perhaps a more stable indicator of the upward trend in Japanese businesses’ interest in India—permission had been granted for 878 such technology collaborations through May 2009, placing Japan third in the list behind Germany and the United States.

Car manufacturer Maruti Suzuki is the best-known success story among Japanese firms tying up with Indian partners. Now in its 29th year in India, the company makes one in every two cars sold in India. Other big hitters among the approximately 700 Japanese firms with operations in India are Asahi Glass, Honda, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Panasonic, pharmaceutical maker Ranbaxy (bought for $5 billion by Daiichi Sankyo in 2008), Sony and Toyota. Among Japanese small and medium-sized enterprises with a presence in India, rice-milling machine manufacturer Satake is prominent.

Potholes, Power Cuts and Paperwork

The long-standing hesitancy of Japanese firms to invest in India can be put down to four main problems: bureaucratic red tape, in the shape of complicated taxation, customs clearance and land acquisition and utilization systems; backward infrastructure, including unreliable power supply, poor roads and port facilities; pro-labor policies resulting in numerous labor disputes; and chronic security risks from ultra-left-wing and Pakistan-linked terrorist groups.

The Indian government has moved in the past decade to prune the thicket of red tape that foreign firms targeting India have faced—a hangover from the “License Raj” system that operated in the four decades until 1990, when India ran a Soviet-style command economy—and create a more investment-friendly climate to attract investment from overseas. FDI policy rationalization and liberalization measures adopted by New Delhi have seen steadily increasing inflows of foreign investment. Between April and August 2010, total FDI inflows into India totaled $11 billion, a 28 percent decline on the $15.3 billion posted for the same period the year before, but five times the comparable figure of $2.2 billion five years previously. The cumulative amount of FDI into India from August 1991 to August 2010 stood at $140 billion. Japan’s share of that was a miserly 4 percent. But deregulation clearly has a long, long way to go: The World Bank rates India 134th out of 183 countries for ease of doing business in its 2011 list. In the same list, India stands at 177th in terms of dealing with construction contracts and 182nd for enforcement of contracts (the respective standings for Japan, by comparison, are 18th, 44th and 19th).

Boom Times Set to Continue

For P.N. Karanth, the avuncular secretary of the Indo-Japan Chamber of Commerce & Industry’s Karnataka branch, Japan’s increased interest in India is a no-brainer.

“Coming to India today is inescapable for the Japanese,” said Karanth, who has been doing business with Japan since 1982. “In the next 30 years, India is going to gallop ahead.”

That prediction seems a fair one: In its World Economic Outlook report for October, the International Monetary Fund said the Indian economy will expand 9.7 percent this year, up from the July forecast of 9.4 percent, and the Economist Intelligence Unit sees India’s real gross domestic product growth averaging 6.5 percent annually in 2011-30, which would make the country the fastest-growing large economy in the world during that period.

“Today, if you talk to any senior Japanese executives, they say, ‘I want to be in India,’” said Karanth, who runs well-attended seminars to explain the Japanese way of thinking and doing business to Indian businesspeople, pointing to increased Japanese interest in making India an alternative to China.

“I hear from almost every Japanese business executive that they will have to shift their business interest and focus from China to India in consideration of uncertain business and political relations,” Karanth said. “Japanese don’t make profit on a sustainable basis in China, whereas they make money in their Indian business. Some people say they hardly make a profit in China, and even if they do, they can’t send it back to Japan as there are many restrictions. There are no such issues with India.”

Karanth pronounced the CEPA an “excellent deal” that will help trade between India and Japan “double in the next five years from today’s level.”

Panasonic: Doing Business in India “Not a Piece of Cake”

For Panasonic India, the CEPA will have an immediate concrete benefit, said Manish Sharma, marketing director of the firm, which set up shop in India 17 years ago.

“As of today, Panasonic only manufactures LCD televisions in India—it imports all other product and equipment from its sister companies, including Panasonic China, Panasonic Malaysia, and Panasonic Indonesia,” Sharma said. “The CEPA, once it’s ratified by the Diet, will help Panasonic manufacture a wide range of products in India. It will also help Panasonic contribute to building economic relations between India and Japan and increase investment flows.”

Comparing doing business in India now with 1994, Sharma said: “Till about 2000, we spent time understanding the dynamics of the local market and Indian consumers, but the brand image of quality and durability still had limited penetration. Post-2000, when the Koreans started dominating the market, the entire scenario saw an enormous shift that also diluted the hold of local players in the market.

“From then onwards, the dynamics of business were influenced by various factors, such as changing Indian consumer behaviors, which were heavily impacted by the emergence of a middle class, the young population profile and growing rural markets. Amidst of all this, when Mr. Daizo Ito, president of Panasonic India, came to India in 2008, he understood the dynamics of the industry and identified the potential in the market that was yet untapped and developed a strategy and a philosophy that was essential to keep pace with the growing market size and competitors.

“So you could say that doing business in India isn’t a piece of cake, but a task that can be accomplished only with a clear, focused vision coupled with hard work and sincerity.”

Investment Areas Diversifying

Hiroshi Hirabayashi, who was Japan’s ambassador to India at the time of former Prime Minister Mori’s visit and now serves as president of the Japan-India Association, notes the rapid diversification in areas of investment since his tenure as envoy from 1998 to 2002.

“In addition to the automotive and electrical and electronics industries, shipping and air services, and so on, manufacturing industries such as chemicals, steel products, pharmaceuticals, heavy machinery, generators and turbines, and service sectors like banking, insurance, distribution are also targeted,” Hirabayashi said.

Of the CEPA, which is awaiting ratification by the Diet, Hirabayashi said: “It will surely increase trade and investment and people flows. I’m not sure if it will reduce the commodity trade imbalance. What is more important is to increase economic and human exchanges in all aspects, including services trade, investment and joint ventures, the flow of workers and protection of intellectual properties.”

Dr. Arpita Mathur, research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and an expert in India-Japan economic ties, said the bilateral trade and investment relationship has “remained largely unexploited in its potential” and should get a “much-needed boost” from the CEPA.

“Although Japan’s trade volume with India has increased, it’s still miniscule when you consider that Japan accounts for only 2.5 percent of India’s trade volume,” Mathur said. “The figures pale completely in comparison with the Japan-China quantum of economic connectivity. There’s also a compelling need to diversify the bilateral trade portfolio, which will hopefully come true after the CEPA comes into force, considering that many obstacles and hurdles will have been removed under its provisions.”

Mathur added that Tokyo and Delhi are also considering looking at trade in untapped areas like rare earth minerals—a resource for which Japan has hitherto relied almost exclusively on China.

Ranbaxy Sees Potential in Rural Market

Pharma giant Ranbaxy is counting on the CEPA covering specific pharmaceutical-related items, such as active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), intermediates, fine chemicals and finished products.

“We hope they will be, so Daiichi Sankyo can provide high-quality materials and products to Ranbaxy at an overall lower cost and vice versa,” Ranbaxy Chairman Dr. Tsutomu Une said. “However, we mustn’t expect any advantage from the CEPA in the science-based review and approval process in respect of pharmaceutical products.”

Daiichi Sankyo anticipates growth “across all sectors of our Indian business” in the next decade, Une said. “Innovative pharmaceuticals, generic pharmaceuticals, over-the-counter pharmaceuticals and preventive medications, such as vaccines, will be within our scope as more of the Indian population becomes involved in its economic model and incomes rise accordingly.”

While India’s rapidly expanding middle class is obviously an attractive market for pharmaceutical makers, Ranbaxy also has a strategy for targeting rural villagers.

“In January 2010, Ranbaxy launched its Viraat initiative, expanding its sales team by 50 percent in order to expand and boost sales in rural markets,” Une said. “The company has hired around 1,500 new employees, most of whom will sell over-the-counter and prescription drugs in small towns and villages. Currently, the total number of medical representatives of Ranbaxy exceeds 4,000, but Ranbaxy still can’t cover the population that’s growing rapidly nationwide.”

Doing Business in India Challenging for SMEs

Hiroshima Prefecture-based rice-milling machine maker Satake sees ample demand for its products in India, the second-largest rice producer in the world.

“Our market in India is expanding because consumers are starting to demand high-quality products as a result of economic growth,” spokesman Harry Harada said, though he added that “the difficulty of doing business in India has not really changed” since Satake entered India in 1996.

Satake is a firm in the SME sector, which IJCCI Karnataka chief Karanth said “needs help.”

“SME sector companies are the most difficult to handle,” he said. “How do we get in touch with them, how do we bring their knowledge and know-how here? Indians are very happy to work with Japanese firms because their technology is so great, their efficiency is very high and the people are trustworthy. If they can speak English, they can do wonders here tomorrow.”

Helping Japanese SMEs maximize their global export potential is an important part of the job of the Japan External Trade Organization, a government-related organization that works to promote mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest of the world. JETRO India Director General Shinya Fujii said India has attributes that provide “vast business opportunities” for Japanese firms, including SMEs. These he listed as “strong scientific and technical manpower, a vast domestic market—a 300 million-strong middle-class population with considerable purchasing power and another 700 million-strong population whose purchasing capacity is increasing gradually—a vast network of bank branches, financial institutions and well-organized capital and money markets, and abundant natural resources.”

But there are significant demerits that must be tackled, Fujii admitted.

“Basic infrastructure in India is still lagging far behind the international standard,” he said. “Significant development is required to get facilities like road connectivity, power, ports and railways in place. Acquiring land for industrial development, too, is a critical issue in India and needs much consideration from the policy side. Also, the process of clearance of projects is still very complicated, which increases the approval time. Single-window clearance should be made simpler and more efficient so projects can kick off in a reasonable period of time.”

Ranbaxy’s Une pointed out that China still leads India in creating a favorable climate for FDI, having invested heavily in infrastructure development.

“Based on its decision to partner with Ranbaxy, Daiichi Sankyo naturally sees great potential in both the Indian market and Indian companies, but with regard to the overall investment environment, lack of infrastructure development is a disadvantage that is often brought up,” Une said. “This is in contrast to China, which is currently devoting significant resources to major infrastructure improvement projects.

“In the future, India will need to make similar, coordinated efforts to upgrade its infrastructure if it wants to attract sustained investment from foreign investors, including, of course, Japan. However, we think that it’s just a matter of time, and that the Indian government is very enthusiastic about developing infrastructure as quickly as possible. We hope the Japanese government will help support this movement more significantly than ever before.”

India Has Long To-Do List

Dr. Hussain G. Rammal, lecturer at the University of South Australia’s International Graduate School of Business and an expert in India-Japan ties, said two areas that the Indian government needs to further reform are “the ease of doing business in India and consistency in the application of regulations,” noting India’s dismal standing in the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings.

“Getting approval from local government bodies for office buildings and permits to import materials can be time-consuming. The bureaucratic setup and the procedural delays can frustrate attempts by foreign firms to grow quickly in India,” Rammal said. “India consists of 28 states, and each state has variations in laws and regulations. The Indian government needs to ensure that foreign firms investing in India face consistency in the application of the laws and regulations. Failure to do so will erode the attractiveness of one large Indian market.”

As well as improving infrastructure, India-Japan trade expert Mathur said India must groom a disciplined workforce, damp down labor unrest and tighten governance.

“The sheer presence of a vast labor and human resource is not sufficient—they also need to be infused with a certain sense of discipline, ethics and orderliness,” she said. “Also, steps have to be taken to ensure that an impression of a certain political resistance to privatization as reflected in a number of instances like violence in Nandigram (in West Bengal, scene of a bloody protest in 2007 against the creation of a special economic zone) is not given to investors, which makes them skeptical about investing. And governance issues in general, especially homeland security and widespread corruption, have to be handled with the utmost urgency in order to ensure India becomes an attractive destination for foreign firms.”

IJCCI’s Karanth echoed Mathur’s assessment of the Indian labor force.

“Indians have brains, though they lack discipline,” he said. “But we can be disciplined. The Japanese are very good at making people do the work properly. Look at the Toyota factory—they work like the military there.”

Prospects Bright for Future Cooperation

A sign of the optimism over the potential of closer India-Japan business ties is a plan Karanth outlined to build a 1,000-acre industrial park in Bangalore for firms making electronic, electrical and auto components.

“The Karnataka government is very keen and has sanctioned the project in principle. The Japanese would own the land and build the infrastructure as they’ve done in Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam,” Karanth said of the project, which he has been pushing for the past year, adding that he was waiting for a Japanese company to come forward and buy the land.

“They should move fast on this because Indian government decision-making is flimsy, and the price of land going up,” Karanth said. A high-speed rail link from Chennai to Bangalore that, Karanth said is also on the drawing board, would make the business park an even more attractive proposition.

Japanese heavy industry, meanwhile, is desperate for a slice of India’s $150 billion civil nuclear energy pie. Toshiba, Mitsubishi and Hitachi have been lobbying the Japanese government hard to seal a nuclear deal with India. Hammering out a deal, former envoy Hirabayashi said, will be a delicate matter for Japan, the only country to suffer attacks with atomic bombs.

“The Japanese government wants to find a good formula to reconcile its willingness to cooperate in this sector and Japanese people’s concerns about the need to uphold the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty,” Hirabayashi said. “How to accommodate their concerns and Indian government nuclear policy will not be easy. I hope the two governments will find good formulas to reach an agreement.”

Given the willingness of India and Japan to endeavor to accommodate each other’s concerns in trade and political negotiations conducted over the past decade, this seems more than likely. Both countries can confidently look forward to a rewarding commercial relationship long after the honeymoon is over.