Obscure Obsequies: Japan's Changing Funerals

CONTENTS

Japan's Changing Funerals

In 1993 actress Takiko Mizunoe held a “living funeral.” She was 78, the end could come any time. Meanwhile she was healthy, vivacious, fun-loving – so why not? Why be a corpse at your own funeral when you can be its host, saying farewell to your nearest and dearest in your own way, laughing and crying with them, basking in their tributes and eulogies?

“I can’t tell you how marvelous it felt,” she said the next day. “Body and soul, I was washed clean. It was like a rebirth.”

Here was something new in that aspect of life – death – least susceptible to change. Death is sacred, solemn, and awesome – at least it was. Custom, if not religion, rules supreme – until it ceases to, and then suddenly one innovation begets another. From the “living funeral” comes the “happy funeral” – a funeral tailored to individual tastes. By the time Mizunoe died in 2009 at age 94 the funeral revolution she helped launch was in full swing. That year Japan’s most famous international celebrity, the comedian-actor-director-writer Takeshi Kitano, held his own living funeral – on his own TV show. “At my funeral I want people to drink and have a good time,” he said. “Say whatever you like about me – I won’t hear you anyway.”

Happy Funeral or No Funeral

Irreverent individuals are not new. What is that now is they are representative of their time. Go to any Japanese bookstore and you’re likely to find a shelf full of tomes on traditional funeral etiquette. The rules are strict and detailed; it’s easy to go wrong, and until recently few wanted to. A mourner must know what to wear (black suit, white shirt, black tie for men, black dress or black kimono for women), how much condolence money to present (between 3,000 yen ($35) and 30,000 yen ($350), depending on relationship to deceased), what kind of envelope to put it in (a special black and silver one called kodenbukuro (shown below)) and so on.

So much for decorum. Then there are the books, newer for the most part, that poke a finger in the eye of all that pomp and formality. Happi na Ososhiki ga Shitai! (We Want a Happy Funeral!) (2007), is one. Another takes the funeral revolution one step farther – into the beyond, one might say. It’s title is Soshiki wa Iranai (We Don’t Need a Funeral) (2010).

Happy funeral? Think of it this way, suggests Hiroyuki Wakao, producer of “happy ending” who wrote Happi na Ososhiki ga Shitai. A funeral is “a ceremony commemorating your graduation from life.” Think of death, he says, as a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and “make your funeral the greatest event of your life.”

His book is a catalogue of colorful alternatives to the grim, solemn, stolidly formal, outrageously expensive, ritual-infused Buddhist funeral that was all but a matter of course in Japan as little as a generation ago. Would it have amused or horrified people back then to be asked to consider, for example, a wine funeral, a jazz funeral, a rock’n roll funeral, a karaoke funeral, a “natural” funeral, a cyberspace funeral, an outer space funeral? Our entire society is based on multiplying choices for autonomous individuals. Why should funerals alone be set in stone when everything else in life is fluid? Why shouldn’t a funeral be a party if the deceased was a partier, or a film festival if he or she loved movies? What a funeral can be, in Wakao’s view, is limited only by the limited imagination. “A mature society,” he observes, “is one in which there is room for various values and ways of looking at things” – funerals included

Limitless possibilities must include that of jettisoning the rite altogether. That’s the option explored by religious scholar Yuya Shimada in his bestselling Soshiki wa Iranai. “A wedding,” he told the magazine Shukan Economist last September, “leaves you with memories, with photographs. A funeral, after all the money you’ve spent on it, leaves you with nothing. I simply do not see the point.”

Nor do a lot of other people. An Asahi Shimbun newspaper poll last year found no fewer than 36 percent of respondents willing to at least consider the idea of dispensing altogether with ceremonial internment.

Natural Funerals Is In

“Many Japanese,” writes Wakao, “picture their spirits joining those of their ancestors after death and, together with them, watching over and protecting their living descendants.” It’s true, but a diminishing truth. Increasingly, death is seen less as a return to the ancestors than as a return to nature.

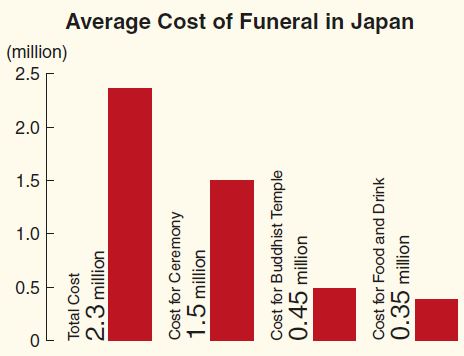

Nature is all-important in this era of heightened environmental awareness, and graveyards, as more and more people are coming to realize, take up more space than this narrow, congested land can spare. No less important, in a lingering recession, is financial prudence. The traditional Japanese funeral is anything but economical. It is probably the most expensive form of burial in the world, costing, on average – when you factor in such more or less obligatory trimmings as a posthumous Buddhist name, offerings to monks, and assorted gifts to mourners – 2.3 million yen ($27,000), five times as much as an average American funeral, 20 times as much as a British one. You can be “buried” in outer space more cheaply than you can in a Japanese graveyard.

“Natural” funerals are simultaneously very old and very new – old in the sense that in early Japan the little-regarded common people customarily scattered the remains of their dead in the sea or in the mountains, burial being the privilege of the more dignified classes; new in that their modern revival as a popular alternative to universal grave burial dates back only to 1991. The spearhead was a non-profit organization called the Grave-Free Promotion Society (GFPS) of Japan.

The first hurdle it faced was a question of law. Was it legal to scatter cremated remains in public natural settings? Elsewhere the practice had a long and illustrious history. Among the notables whose “cremains” have nourished fish or fertilized forests are Friedrich Engels, Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Einstein, opera singer Maria Callas and U.S. ambassador to Japan Edwin Reischauer. But in Japan the vague wording of the relevant laws fed the prevailing assumption that it was illegal. “We argued,” explains GPFS president Mutsuhiko Yasuda on the NPO’s website, “that natural funerals violated neither the criminal law nor the legal code regulating cemeteries and burial.”

A precedent was needed, and GFPS set it with its first natural funeral at Sagami Bay in Kanagawa Prefecture, near Tokyo, in 1991. No one challenged it. Subsequently the Justice and Health ministries gave their qualified okays – provided, they said, the cremains are scattered “in the spirit of moderation.”

Since then the society has conducted more than 2600 natural funerals, at sea or in mountains across the country. Ceremonies are collective or individual, the former costing 48,000 yen ($560) to 110,000 yen ($1,290), the latter 69,000 yen ($810) to 177,000 yen ($2,080).

“We believe,” says Yasuda, “that we opened a new chapter in the history of Japanese death customs.”

It is more a book than a chapter, so rapidly have natural funerals gone from marginal to mainstream. A 2007 poll by the Japan Consumers’ Association found 39 percent of respondents tentatively interested in the concept, and 21 percent more or less committed to it. The range of choices has expanded accordingly. It was only a matter of time before it came to embrace a symbol especially dear to Japanese hearts – the cherry tree.

The “cherry tree funeral” is the special domain of the NPO Ending Center, which has turned a corner of the Izumi Joen Cemetery in Machida City, Tokyo, into a little grove of cremains-fertilized cherry trees. It is Japan’s first “cherry tree funeral ground.” When the trees bloom in spring, friends and loved ones gather for memorial services under the blossoms – reflecting, perhaps, on how much truer to the spirit of life and death are the beautiful, transient blossoms than the imperishable, chilling gravestone. A price comparison might also cross their minds – a cherry-blossom funeral for one costs about 400,000 yen ($4,700).

But why be earthbound? How you feel about this will depend on whether you view death as a return to the soil from which we spring, or as a return to the cosmos from which we spring. If the latter view draws you, Balloon Kobo Inc. of Tochigi Prefecture had you in mind when in the 1990s it developed its own variation of the natural funeral – the balloon space funeral. Balloon Kobo has been in the balloon advertising field for 35 years. Its balloons are made with sap from gum trees. The firm claims they are 100 percent biodegradable, causing no harm to the environment when they break up 30 km above the ground after a roughly 90-minute flight, scattering the finely powdered ashes they have borne aloft in a gentle return to Earth and to nature, to nurture whatever they chance to fall upon. Standard price: 188,000 yen ($2,110).

Society of No Relationships in Japan

A funeral revolution presupposes a social revolution. A stable society doesn’t overturn sacred age-old death rituals. Only a society in flux does. Japan’s social revolution is quiet but dramatic. An observer who has been away for 20 years would scarcely recognize the nation today. Its population is starkly older, poorer, less driven, more urban, more anxious, less optimistic, less male-oriented, more individualistic, more isolated, freer, less committed to either roots or long-term goals, than at any time within memory. Traditional funeral practices reflected traditional values rooted in a traditional society that no longer exists. Conspicuously moribund is the old family system. The traditional Japanese Confucian family, or “house,” is a unit comprising several generations headed by the eldest male whose honors and responsibilities will pass as a matter of course to his eldest son. Symbolic of the house, of continuity, of undying devotion to the ancestors, is the family grave, repository of the ashes of males born into the family and females marrying into it.

Few allowances were made, in this traditional system in which so much of the course of a person’s life is determined at birth, for individual preferences, individual choices, and individual freedom. First symptom of a new order was the break-up, or “nuclearization,” of the extended family. Elders lost their influence on a nuclear family’s life. Now the nuclear family itself is crumbling, as individual fulfillment becomes the sole measure of happiness. Husbands, wives and children live together in deepening mutual estrangement – when they live together at all; the divorce rate is climbing. Wives, more assertive than ever before, refuse in many cases to be buried with their husbands’ families. Twenty-seven percent, according to a 2003 survey cited by Wakao, balk even at being buried with their husbands, preferring burial with a close friend or a treasured pet.

Japanese people are living and dying alone as never before – an inevitable consequence of declining marriage, declining childbirth, and a sharply extended lifespan. The potential horror of it all came to light last summer – the summer of the “missing centenarians.” What had happened to them? Hundreds of people over 100 years old, blithely assumed by local officials to be alive and receiving their pensions, were suddenly discovered to have vanished, in many cases a very long time ago. They symbolize a larger problem. Nationwide some 32,000 elderly people a year die alone, often in wretched circumstances, sometimes months before anyone notices.

A new expression came into vogue last year that sums it all up. Japan had become a muen shakai, a society of no relationships. That’s a very radical departure from the tight web of family and social ties that endured, however frayed, until the economy crashed in the 1990s. Life being no longer the same, death is not either. The funerals of today are, along with much else that might be said of them, those befitting a muen shakai.

A Diversity of Death Styles

The term chokuso – “direct funeral” – was coined 10 years ago by “funeral journalist” and author Hajime Himonya. Chokuso means unceremonious, unceremonial cremation. It’s a euphemism for no funeral.

Himonya was not promoting the direct funeral, merely noting its emergence amid social changes favorable to it. Writing in the September 2010 issue of the monthly magazine Takarajima, he drew a quick sketch of modern funerary history. During and immediately after the war, a dignified funeral was scarcely possible. The return to prosperity invited a backlash. Funerals got grander and grander. By the “bubble” years of the 1980s “mourners” typically numbered in the hundreds, relatively few of whom had more than a passing acquaintance with the deceased.

The bubble burst, and austerity set in. Funeral ceremonies were scaled down, and down again – all the way down, in many cases, to the immediate family. Partly the consideration was economic, partly also philosophical. The two are linked. Financial constraints led people to reflect that after all they were not believing Buddhists, only nominal ones; their ties with their local temple were at best tenuous – and did the deceased loved one really need, for example, a posthumous Buddhist name, the bestowal of which involved an enormous expenditure hitherto unquestioned? Was it really necessary to make the customary exorbitant money offering known as ofuse to the temple priests?

Shimada, the author of Soshiki wa Iranai, adds another point: the expanded life span has imposed such huge end-of-life care costs, burdens and anxieties on families that the funeral becomes a mere afterthought, the survivors too weary and financially drained to give it serious consideration. “For my part,” Shimada tells Shukan Economist, “nothing at all is just fine. You die, you’re cremated – the end. At least that option should exist.”

A diversity of lifestyles will naturally find its reflection in a diversity of death styles. What would Confucius think of happy funerals, space funerals, living funerals, no funerals? Would he, as the saying goes, turn over in his grave?

Perhaps he would, for he said, “Conduct the funeral of your parents with meticulous care.” Or perhaps he would not, for he also said, “Even if I were not given an elaborate funeral, it is not as if I would be dying by the wayside.” As Himonya says, “It’s not just a question of how much money you spend” – or of how meticulously and in accord with precedent you conduct the ceremony. The important thing is “for people to think more deeply about human death.”

That’s the funeral revolution in a nutshell – an entire society thinking afresh about the oldest, most poignant and most insoluble of mysteries: death.