Japan's Sake Market Going International

CONTENTS

Japan’s Sake Fan Surge Abroad

Gekkeikan’s Overseas Sake Business

Japanese sake exports are increasing every year, at such a rate that they have almost doubled over the past 10 years. It’s not just Japanese expatriates and Nikkei (locals of Japanese descent) who are drinking it. Japan is not the only country where it’s produced. Sake exports from one foreign country to another, without going through Japan, are moving briskly. On the other hand, however, there are still many countries and regions where sake is unfamiliar. For each sake producer in Japan, different popularization strategies are called for in different parts of the world. Based on an interview with Gekkeikan’s Director of Trade, Mr. Kenichi Kajihara, formerly the president of the company’s U.S. subsidiary, we present an overview of recent conditions in the sake business overseas.

-1024x748.jpg)

Cocktail-style Sake Popular in Brazil

The cocktail called saquerinha or saquepirinha is popular in Brazil. As indicated by “sake (saque)” being attached to the beginning of the word, it has a sake base. The original Brazilian national cocktail is the caipirinha. This tropical cocktail is made by adding sugar and lime to pinga, a distilled liquor made from sugar cane with a high alcohol content. A saquerinha is a variation made by replacing pinga with sake.

Its popularity spread through Sao Paolo in the mid-2000’s. In addition to the smooth taste, there are indications that a big factor in its popularity is Brazilians’ health-consciousness. Sake’s alcohol content is about half that of pinga. As sake itself has a sweet taste, the amount of sugar can be reduced or, depending on the sake, eliminated completely.

As if to confirm the popularity of the saquerinha, in the brief period from 2006 to 2008 the amount of sake exported to Brazil grew by almost five times. There has been a slight drop since then, but this has been offset by an increase in local production and imports from the U.S.

Speaking of sake cocktails, the big domestic sake producers have started selling them overseas, but we seldom hear of success. This is probably because these producers only think of the cocktails as an extension of sake. Brazilians probably see the saquerinha as one version of their own familiar caipirinha; whether they have a strong awareness of sake is unknown. There are many popular variations on the caipirinha, such as the vodka-based caipiroska.

With many people of Japanese descent in Brazil, there has long been a demand for sake, so there are already local companies producing it. In this age of the modern global economy, however, when talking about the increasing popularity of sake overseas, we should probably say that this development points to growing demand among the non-Japanese majority even more than local Japanese communities (ex-patriates and Nikkei). With this kind of development, ways of drinking sake will appear that are unimaginable to Japanese people.

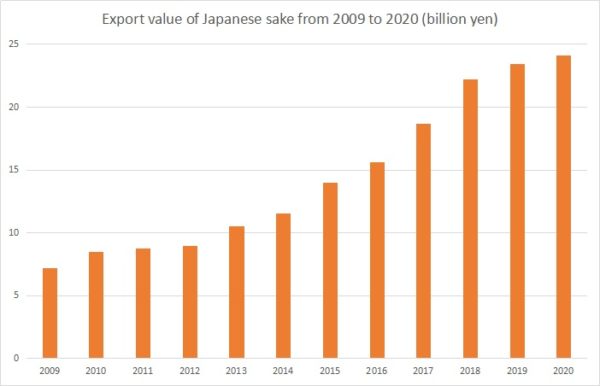

Figure 1 – Changes in the Amount of Sake Exported

Big Producers Expanded into the U.S. in the ‘80s

Apart from a one-time slowdown in 2009, when the worldwide economy stagnated due to the effect of the Lehman Shock, sake exports have been doing very well. (Under the influence of the nuclear accident, however, the prospect for 2011 is for sluggish growth or a decrease from the previous year.) On the basis of volume, in the 10 years from 2001 to 2010, they almost doubled.

Why has overseas demand for sake increased so much? The media says the main cause is that, as exports increase every year, they also increase the “Japanese food boom.” But it is doubtful whether this yearly growth should be called a “boom.”

According to Gekkeikan’s Director of Trade, Mr. Kenichi Kajihara, “The Japanese food boom in the U.S. occurred during the latter half of the 1970s.” Americans were becoming more aware of healthy eating. On the west coast Japanese food, especially the healthy rolled sushi such as “California rolls” made with kanikama (imitation crabmeat sticks) and avocado, became fashionable. In the 1980’s this trend spread throughout the country.

Japanese restaurants increased with the growing popularity of sushi, and naturally the demand for sake also rose. Mr. Kajihara says, “Because Western people place great value on TPO (time – place – opportunity), they drink sake when they go to Japanese restaurants.” As a result, sake exports to the U.S. have increased. However, from the American point of view goods imported from Japan tend to be expensive. Therefore, Ozeki (then called Ozeki Shuzo) and Takara Shuzo started local production in California in the first half of the 1980’s.

In the second half of the 1980’s, the popularity of Japanese food had still not waned, and Gekkeikan also started expanding into the U.S. In addition to the fact that domestic competitors from Japan who were already there, it took about a month for exported goods to be delivered, and this situation was being aggravated by the effect of the continual rise of the yen. At that time, Ajinomoto had know-how about doing business overseas, so Gekkeikan sought the cooperation of Mercian (then called Sanraku), the part of the Ajinomoto group that handles wine. In 1989, the U.S. subsidiary of Gekkeikan was created.

Dealing with Non-Japanese Wholesalers Paid off

The head office of Gekkeikan Sake (U.S.A.) is in Folsom, in the suburbs of Sacramento, California. Mr. Kajihara explained that the water in Folsom is well-suited for sake brewing.

“There is a major rice-growing area in the northern part of California, but rice can be transported. Water, however, cannot be transported. Therefore, when we were looking for a place with good water, it turned out to be Folsom. With a Kikkoman soy sauce factory nearby, it is a suitable location for production using water.”

They initially set up production and sales in the U.S. in the first half of the 1990’s, and in order to differentiate themselves from other companies that had previously launched subsidiaries, they focused on household use – supermarkets and liquor shops – rather than Japanese restaurants. A big reason that they could have the retail market was that, instead of using a Japanese wholesaler like the other companies, they used an American distributor in New York. This would later become an advantage for Gekkeikan U.S.A.

In the early 90’s when the Japanese bubble economy began to collapse, if you were talking about a place to enjoy sushi it would be a Japanese-owned Japanese restaurant. And yet, probably because of the vigorous growth of the U.S. economy through the rest of that decade, ownership of Japanese restaurants gradually shifted, unnoticed, to non-Japanese.

According to Mr. Kajihara, “probably only about 20 percent of the owners are Japanese.” The other 80 percent are of Asian descent, such as Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese and Myanmarese, and Hispanics are also prominent. For example, at a Chinese restaurant the revenue per customer is low, and the owners often switch to a sushi shop, which has a relatively high unit price. Also, there are French and Italian restaurants where a sushi counter has been set up, so the idea that “if you eat sushi, it’s a Japanese restaurant” has crumbled, he said.

In other words, the traditional “sushi = Japanese restaurant = Japanese owner” connection has fallen apart, replaced by a typically American jumble of races and ethnicities.

Gekkeikan U.S.A. had already been dealing with non-Japanese wholesalers, so with these changes their business market has increased. It has been over 20 years since the company was established, and the business market now makes up 60 percent of their sales. However, they are still making efforts in the household market too, so they are balanced in comparison with other companies, whose business markets tend to be around 80 percent of their sales.

Chilled Version Is Increasing

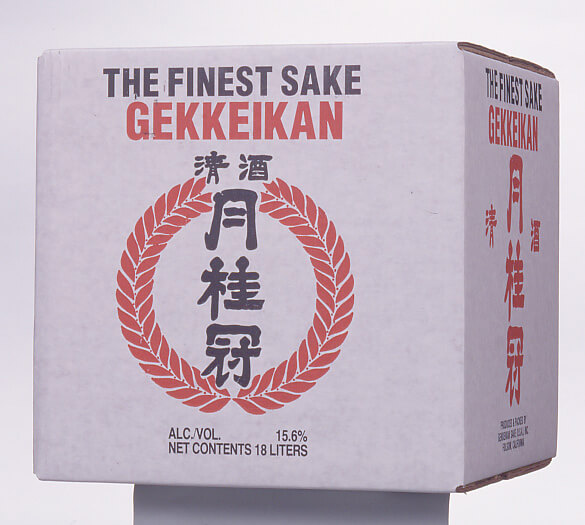

When talking about sake for business use in the U.S., what comes to mind is an 18-liter box (cubic container) of junmaishu (sake made without added alcohol).In America, adding fermented alcohol means it is considered hard liquor. A special permit is needed to sell it, and the tax rate is higher. For sake producers there is not much economic advantage in this, so they make junmaishu, a soft liquor.

Many Americans drink sake as atsukan, meaning heated. To heat the sake, restaurants install a sake-heating machine. Sake flows down through a pipe into the machine from an 18-liter box on top, and heated sake automatically comes out of the tap. It is poured directly into a sake bottle and served to the customer.

To Americans, drinking heated alcoholic drinks is unusual; sake producers used that as a selling point and made atsukan the established serving method. On the other hand, previously, the premium level (and higher) ginjo class of sake, which is drunk chilled, was expensive to import, and the U.S. subsidiary didn’t produce it, so drinking chilled sake did not catch on.

What comes out of the above-mentioned sake-heater’s tap is more correctly called “hot sake” than “warm sake.” According to Mr. Kajihara, “Americans like to drink sake that is steaming hot,” and “they can often be seen asking for it to be reheated if it’s a little lukewarm.” They drink it “extra-hot,” heated to over 55°C. Unless they are a real connoisseur, they are unaware of the concept of “warm sake.” Stuffing sushi rolls into their mouths while drinking piping-hot sake is the typical American style of eating Japanese food.

However, despite the preponderance of hot sake, signs of change began to appear in the late 1990’s. With the long-term economic expansion called the “new economy,” American consumer confidence was strong. In these circumstances, with increasing awareness of local regional sakes imported from Japan, some high-income earners and gourmet-lovers started to ask for chilled sake.

In 2000, Gekkeikan, too, began to produce and sell premium ginjo sakes such as “Haiku” in the U.S. As the price of products made locally was relatively cheap compared to imports from Japan, chilled sake became more affordable for Americans. According to Mr. Kajihara, the locally-made products are dry with somewhat high acidity, similar to white wine.

According to a 2005 JETRO (Japan External Trade Organization) study of 96 Japanese restaurants in four U.S. cities (Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and Chicago), more than half of the restaurants surveyed responded that over half of their clientele orders chilled sake (including normal temperature), and most of the customers who ordered chilled sake were non-Japanese (2005 Fiscal Year International Food Industry Feasibility Study - Export potential and market trends for sake and shochu in the U.S.). JETRO conducted this study between August and October, so we should consider seasonal factors to have boosted the ratio of chilled sake, but this suggests that at least more non-Japanese Americans are aware of chilled sake than before. When viewed at the national level, though, it seems that in the mainstream, atsukan from an 18-liter box is still the norm.

From a Single Phone Call to a Korean Subsidiary

There is a makkori (Korean rice wine) boom in Japan. But did you know that the popularity of Japanese sake is also rising in South Korea? The image of Koreans being strictly shochu (distilled spirit) drinkers is strong, but it is not necessarily true. Suddenly, in the latter half of the 2000’s, sake exports to South Korea rose sharply, and, almost unnoticed, it became a major destination for exports, second only to the U.S.

The first factor in the increased popularity of sake in South Korea is the increase in the number of Japanese-style izakayas. There is the same pattern in these izakayas as in restaurants the U.S., of a growing awareness of Japanese food and sake as a “set.” The popularity of imported wine has risen mainly among health-conscious young women, but as sake also has a relatively low alcohol content compared to shochu, it has a good reputation, which is the second factor. The third factor is the decrease of the liquor tax on sake from 70% to 30% in 2002. The price became cheaper for consumers, and demand rose.

Imports of sake in South Korea did not just start in recent years. Trade was liberalized in 1994, and after that, the first Japanese company to expand the sale of sake there was Gekkeikan. As early as 1995 they set up an import and sales company, Gekkeikan Sake, (Korea) Ltd., as a joint venture with a Korean, Suh Jeong-Hoon.

Mr. Kajihara has a strong memory of Suh Jeong-Hoon. In 1994, when he was a manager, out of the blue he had a phone call from Mr. Suh, a complete stranger. Mr. Suh said, “Since the sake trade has been liberalized, I want to do business with Gekkeikan.” For their part, Gekkeikan was interested in South Korea, so Mr. Kajihara replied, “Let’s get together soon and talk about it face to face”; he was surprised to learn that Mr. Suh was calling from nearby Chushojima station in Kyoto where the Gekkeikan’s headquarters is located.

They decided to have lunch together there. Mr. Kajihara heard that Mr. Suh had approached other major sake brewers, but none of them would partner him. As Gekkeikan was one of Japan’s leading sake companies, he had indeed been hesitant to contact them, but since the other companies had all refused him he had boldly made the phone call.

That single phone call turned out to be the beginning of the establishment of Gekkeikan Korea. After that, until the above-mentioned sake boom, it could be said that the company had a monopoly in the sake-importing business in South Korea. Imports were not necessarily only from Japan – nowadays more is imported from Gekkeikan U.S.A. After World War II, the techniques of Japanese sake producers who had originally expanded into Korea before the war were taken over, and sake had been produced and sold using South Korean capital, so for Koreans it was not essential that sake be made in Japan.

According to Mr. Kajihara, if you calculate the total sales of Gekkeikan U.S.A. and affiliated companies such as the Shanghai sales office, their proportion of Gekkeikan’s overseas sales is about 12%. Currently, the U.S. subsidiary produces 31,000 koku (5,580 kiloliters), which would rank them 15th on the domestic scale. In the near future, he said, that company alone is expected to grow to the point where, if it were in Japan, it would be in the top 10.

On the other hand, the export environment has not been very good lately. Still, in the case of Gekkeikan, since they can export throughout the world from Gekkeikan U.S.A., established the sales office in Shanghai in July 2011, and have arranged for local production to be handled by contract manufacturers, then compared to other sake makers who have been focusing on exports, their business situation is stable and they may be able to expand.

A very popular export of Gekkeikan is the sparkling sake “Zipang.” Unlike carbonated beverages such as the sake highballs that have been much talked-about recently, the bubbles are caused by fermentation so they don’t disappear over time. Because it can be drunk like chilled champagne, it is very accessible to Westerners. Originally it was aimed at the domestic market but is being ordered more in the U.S. than in Japan, and now 80% of it is exported there.

It’s no wonder that, with its distinctive bubbles, “Zipang” is in demand in the U.S., but surprisingly, Gekkeikan’s finest junmai daiginjo “Horin” is also very popular. Almost half of it – 40% - is exported overseas, which tells us that foreigners have become accustomed to drinking premium sake. In the U.S., a 720 ml bottle sells for 50 dollars. While regional jizake brands such as Kubota and Hakkaisan are no longer unusual over there, “Horin” is doing very well as a premium sake from one of the big producers.

On the other hand, even if we combine Gekkeikan’s exports from both Japan and the U.S., there are still many countries and regions where sake has not caught on yet. Russia, for example. When Mr. Kajihara promoted sake as “rice vodka,” the response was a disaster: “The alcohol content is too low for this to be vodka.” Even though in other countries, the low alcohol content is a selling point for health reasons, he learned that that won’t work in Russia.

However, as in the case of Brazil mentioned at the beginning of this article, sometimes sake will become locally popular for reasons that Japanese could not have imagined. There is probably still room for sake to evolve into a “global product.”

-300x200.jpg)