Interview with Makoto Shinkai, Animation Director

Astonish the World with the “Japan’s Landscape”

Perhaps one of the distinctive characteristics of the animated movie director Makoto Shinkai is that for all the movies he has been involved in to date, including his best-known work “5 Centimeters Per Second” (2007), he has doubled up as original creator, script writer, editor, cinematographer, and director to create movies in which personal world views are intimately opened up to the viewer.

Initially, Shinkai employed technologies such as CG that he had honed during his time working at a video game company, such as in his debut work as a bona fide director, “Voices of a Distant Star” (2002). The visuals and artistic elements of “Voices of a Distant Star” were handled entirely by Shinkai himself. Despite being made by the hands of a lone individual, the movie was of such high quality – particularly the unconventional backgrounds – that it turned preconceived notions of animation upside down and showcased Shinkai’s rare talent.

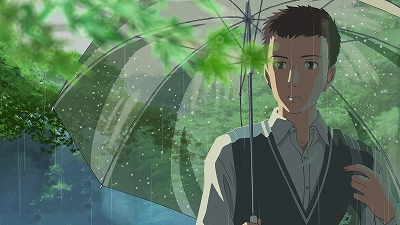

Shinkai’s latest work, “The Garden of Words” (2013), is a movie filled with Shinkai-esque story arcs and landscapes, and is generating a lot of attention. We asked him about the emotional content of his highly distinctive style and the things that fuel his creativity.

The significance of showing real places in animation

– Even among all the movies you’ve made, I think the latest, “The Garden of Words”, is your most wonderful work to date.

Shinkai: Thank you very much. This movie was shown in Hong Kong and Taiwan at the same time it was shown in Japan, and after that we plan to release it overseas as well. This time, I made the movie with the assumption that it would also be seen overseas – although I can’t be sure whether it will be seen in theaters, on Blue Ray DVD, via download services such as the iTunes store, or even by illegal copy!

However, I personally don’t know how to make something that would work as a business overseas as well, so what I kept in mind was that I wanted to make something that would be enjoyed by all the people whose faces I could specifically remember from when I went to London in 2008. Over a year or so in London, I got to know friends from various countries – people such as movie distributors and those in the theater business – and my past movies helped me to form connections with them.

Another thing, albeit unsophisticated, is that the movie also includes my urge to show off my hometown, to say, “Doesn’t Tokyo, where I’m living now, have some beautiful places?”

– Even when viewed from a global perspective, I think your depictions of landscapes such as the Japanese-style garden in Shinjuku and the area around Shinjuku station in the rain in particular show the rich ingenuity and beauty of animation expression. What is the significance of the landscapes in this movie?

Shinkai: I wanted to present the landscapes that we usually look at in a beautiful way. When you use a real place as a setting, you have to show the reason why you are showing that place in animation form. The audience is not just overseas, but also Japanese people who know the actual places.

Not just me, the director, but also the other staff on this movie had to think about what they needed to do to make sure no viewers would think that using live action footage would have been better. The backgrounds are presented in a subjective way; including me, the individual staff members who worked on the background art considered how they personally perceived those landscapes and which ways of looking at them made them beautiful. For all my movies, and not just this one, I’m looking for a theme in the visuals of each and every scene. Although the focus will sometimes be the characters, voices, or music, as the setting is an actual place this time, I focused on themes such as “Shinjuku in the rain” for each scene.

What I ask myself at those times is, for example, “How can I draw the puddles so that viewers will be taken aback by them?” In other words, visuals for each and every scene that will astonish people, but not to the extent that the visuals obstruct the flow of the story. It might be the use of a certain color tone or angle. Drawing the scenes only started once we had decided what it was going to be that would astonish people.

To be specific, we try to present backgrounds with such a level of density that you can’t tell whether it’s a photograph or drawing just at a glance. However, although the volume of information contained in the drawing may be enough to make you think it was a photo, as the background has been drawn by hand, the information it contains has actually been thoroughly sorted and filtered, which makes it look clearer.

In the real world, the surface of a pond would have leaves, twigs and various bits of trash floating on it, and the colors reflected from it would include the gray of the rain-filled sky as well as green. However, we reimagine the water surface as clear and deep green in color, so the drawing becomes abstracted yet still has a relatively high density and amount of information, which makes the viewer think, “I’m sure I know this place, but seeing it like this makes it look like something fresh and new.”

Movie-makers Cannot Detach Themselves from “the Atmosphere of Society”

– I’m sure there have been lots of comparisons with your best-known work “5 Centimeters per Second”, but how do you feel about that?

Shinkai: It perhaps goes without saying, but both animation technology in general as well as our own skills have evolved since “5 Centimeters”, so there’s no doubt the newer work rates higher simply in terms of being a more finished article. However, the underlying message in “The Garden of Words” hasn’t changed. Both movies put out the message “Even if a certain someone doesn’t think of you in the way that you’d like, try to move on without becoming desperate.” In love, for example, if the person you like won’t fall for you, you might feel like the world has ended. What I want to convey is that you yourself haven’t ended.

Another difference between “5 Centimeters” and “The Garden of Words” is that the former is a story about realizing one’s own feelings of helplessness, while the latter is a story about understanding that others are different people to you. The main character of “The Garden of Words” is a high school student who wants to become a shoe maker, and it is set up that way because I wanted to draw someone who grows as a person after learning about others by interacting with their feet. Although it’s also important to grow by learning about your own self, this time, I wanted to try drawing something coming from the opposite direction.

– The Great East Japan Earthquake occurred just before completion of your previous movie “Children Who Chase Lost Voices” (2011). Has the question of what kind of work you should produce troubled you over the two years since?

Shinkai: With the earthquake and tsunami, we truly felt how fragile the ground beneath our feet is, how simple everyday things can crumble away. As “The Garden of Words” was made while experiencing these things, it occurred to me that the landscape of Shinjuku today would definitely not be here in a few decades either. That’s why I strongly wanted to leave my own subjective images of the places I like and live in.

Profile: Makoto Shinkai

Born 1973 in Nagano Prefecture. Majored in Japanese literature at Chuo University. Became a freelance animation director after working for five years at a video game development company. “5 Centimeters per Second” won the best animation award at the 2007 Asia Pacific Film Festival. Other movies he has directed include “The Place Promised in Our Early Days” (2004), “Children Who Chase Lost Voices” (2011), "Your Name" (君の名は。 Kimi no Na wa) (2016), "Weathering with You" (天気の子 Tenki no Ko) (2019).

I also think that movie-makers, as well as being part of society, have to reflect the “social atmosphere” of that society in their movies. This summer, for example, Hayao Miyazaki has released “The Wind Rises”. Given the timing, I think that animating the story of the Zero fighter does have a connection with the atmosphere of Japan today. Although Miyazaki himself denies it, it could send out some sort of message to the countries of East Asia. Even people with such a wealth of talent can end up unwittingly making something that reflects the atmosphere of the times. Subsequently, I have become conscious that I am not completely detached from the times either. The question of how that is reflected in “The Garden of Words” is something that I think I’ll only understand for the first time when I see the movie again from the outside some time later.

Why Japan Makes Works with Such Strong Auteurism possible

– Since you made your debut with “Voices of a Distant Star”, what things have become important to you as you continue to produce works as an animated movie director?

Shinkai: Initially, the impulse of wanting to make movies no matter what was all I had. Back then, though, I was a young man in my 20s and I wanted to make something with my own name on it rather than that of a company. I guess I was a publicity seeker. I quit the game company I was working at pretty much on the spur of the moment and made “Voices of a Distant Star” on my own. Considering what my skills were at that time, animation was my only option. Live-action movies require both cameramen and actors, but with animation, you can create the CG, backgrounds, and characters all by yourself. I can even do the voices for the male characters myself. I couldn’t make the soundtrack, though, so I asked a senior colleague from the company I worked at.

After that, I started making movies with a group of more and more people. Even so, as well as directing, I was also involved in tasks such as the creation of the original story, scriptwriting, storyboard, editing, and cinematography. I have a strong desire to make the stories myself and I’m very particular about the finishing touches for the visuals, so I guess these are parts that I’m not prepared to give way on.

– Do you feel that you would like to leave these tasks to other people in the future?

Shinkai: Of course, if I met someone I could trust with these tasks, I would like to leave them to someone else. For example, I asked Hiroshi Taniguchi to do a large part of the background art on “The Garden of Words”. Although it was my job to instruct on the specific composition of the drawings and, lastly, to give the go-ahead once I’d received them, the person who worked most on the art-related elements was Taniguchi; you could say the backgrounds in the movie are his drawings. He’s an analog kind of guy and loves intricate, picturesque backgrounds. But he’s got digital tools, which is probably why he could produce backgrounds that were all hand-drawn digital backgrounds that leveraged the benefits of analog. For the animation of the characters too, I’ve been leaving the actual work up to other animators ever since “The Place Promised in Our Early Days” (2004).

After that, as the cinematographer, I layer together the backgrounds and characters that others have drawn, add elements such as rain and light, and control the colors to bring everything together. In other words, I control the movie at the point of entrance and the point of exit. If I can be involved at these stages, it guarantees the quality that I’m looking for and allows me to be personally satisfied. I feel that being able to work in this way is something “unique to Japan”.

– Why is that?

Shinkai: Japanese animation offers fertile ground that allows “auteurism” when making a movie. Take Hayao Miyazaki, Mamoru Oshii, or Mamoru Hosoda – their respective auteurism is widely recognized here. Even TV animation is partly like that as well. A market of viewers that will enjoy their work is guaranteed. On the other hand, titles from American companies such as Pixar are completely different. Although each movie has a director, there isn’t as much deviation allowed compared to Japanese animation works. They think of their viewers in global terms that hundreds of millions of people are going to watch the movie. As a result, the stories are structured so that they will definitely be communicated to several hundred million people. However, I think Japanese animated movies only assume viewer numbers of around a hundred million at the very most.

– How many viewers do you personally assume your movies will have?

Shinkai: “Voices of a Distant Star” sold 100,000 DVDs, and although that is physically a large number, I truly experienced a happiness that 100,000 people had watched my movie and I wondered whether what I wanted to say had gotten through to each and every one of them. So, yes; I do kind of wish that number would grow to 1,000,000 or 10,000,000 hereafter. If that many people watched them, my movies would become a general communication tool that people could talk about in place like schools: “Have you seen the new movie?” “Yeah, that character was awesome.”

However, that’s about all I can imagine. I’ve hardly ever thought about being watched by hundreds of millions of people like Pixar movies are. Most Japanese animation works are the same in that respect, and that’s probably why the director is allowed some auteurism.

My strength is also an auteurism that only supposes comparatively few viewers. Although I didn’t receive training at a studio, I was able to become an animation director because I broke through with a movie that I’d made myself, “Voices of a Distant Star”, and socially, I’m given leeway to make adventurous works. My latest, “The Garden of Words”, also has an irregular running time of 46 minutes and some aspects of it were rather challenging experiments for me, such as only using animation to tell a story that lacks any fictional happenings and could be transposed to reality. The fact that I’m able to continue doing things like that I regard as one of my strong points. Continuing to put out things that are different to those from general studios is something I consider to be one of my missions.

Connecting the Length of Self-thinking Time to Movies

– You just mentioned your way of making movies that is unique to you and different to movies made in general studios, but what do you mean by that specifically?

Shinkai: Once a movie is completed, it starts being released in theaters. With that, you start traveling around Japan and beyond to promote it. Once that promotional tour is almost over, from the communication I had with viewers via that movie, I start getting a vague outline of the kind of piece I should draw next. After that, I spend more and more time mulling it over by myself. That, I think, is my way of making movies.

Generally, even while the director is thinking about things by himself, he every day commutes to his workplace in the studio, but I spend over half the year living at home hardly without ever going to the studio. That is where I collect the seeds and spread out the leaves of my next work. While going out for walks and reading various books, I piece together the fragments of the thing I should make next and start forming a conception of it by myself. Once I’ve readied a plan, I present it to the producers at Comics Wave Films, the production company I’ve worked with ever since my debut and we have discussion after discussion. Once they decide that the movie could work, I start writing the script and drawing the storyboard.

This time, for “The Garden of Words”, I made a video storyboard myself that had a running time of precisely 46 minutes. The drawings didn’t move, so the format was like a 46 minute long picture story show. I did the voices myself and polished it to the extent that it could be viewed as a film piece. I spent all of May to September last year revising and touching up the video storyboard. Once the video storyboard is finished, it becomes a rigid blueprint for the work as a whole, so I don’t add any changes.

From October last year, we started working on the movie as a team and completed it in March this year. Although working with the staff is also very important, the time I spend fretting while single-mindedly creating the video storyboard is overwhelmingly long. For the animation industry, where most of the works are not one’s own original creation, my level of auteurism is strong in every respect, in both a good and bad way. That’s maybe the only way I can work.

Works That Do Not Have To Be “Excused”

– As your movies are viewed overseas, from communicating with foreign people, how do you feel they perceive your work and Japanese animation?

Shinkai: Japanese animation is very welcome at festivals and events in the countries I have visited. That’s because such events gather together people who love anime in the first place. Many of them are surprisingly deep fans. Even in a place like the Middle East, where the social system is completely different from Japan, I once heard tunes from Japanese anime blaring out of a car stereo. I visited the driver’s house and there were copies of “Shonen Jump” lying around. Japanese anime looks cool as a form of entertainment, but for people overseas, it’s also a tool for expressing their own individuality. That’s why I do things without excusing or explaining them; I want to make things that are standalone pieces that you can understand by watching them, and yet are interesting.

For example, the “harem” thing in schools – the story about a guy who ends up being popular and for some reason is surrounded by loads of cute girls. Such stories are a given in Japan. Granted, the story may contain plenty of drama, but as a scenario, it’s clearly unnatural isn’t it? Foreign viewers probably don’t understand the actual Japanese school system anyway.

Nevertheless, in one sense, because that oddness sticks out, people love it. Some of them get wildly enthusiastic about it sometimes too. I also want my work to be seen by people with that wildly enthusiastic streak, so I apply creative twists to make movies at a level where they can be enjoyed even if the viewer doesn’t understand the tacit unspoken agreements within Japanese society.

– Lastly, what do you think about the role that animated work can play in society?

Shinkai: I want to make the time spent watching animation something truly enjoyable – stories that keep you in suspense, that you can get emotionally involved in. Of course, I want to make superbly beautiful visuals that move people when they see them, but I’d also be pleased if my work could soothe people, encourage them, or even save them somehow: “I felt energized after watching this movie” or “I hadn’t been going to school or work much, but I felt like giving it another shot” or conversely “I couldn’t go to school or work, but now I’ve decided that it’s fine not to go” would even be okay. For people burdened with emotional scars, I think that animation should fulfill a Band Aid-like role as a sticking plaster for the time until their wounds have healed; a helping hand that lets them move on.

I think people, whoever they are, go about their jobs while wondering about what kind of meaning they have socially. Moreover, the bigger the role they can play – however small that may be – the more their happiness with their work increases. I was born in Japan, so I want to do something that could be some sort of use to the people around me and the land where I grew up. That’s why I’d be pleased if, via my work, I could give the viewer an extra positive effect in addition to simple amusement.