Kojiki: the Oldest History Book in Japan

CONTENTS

- Read Kojiki to Understand Japan and Japanese

- What Is "Kojiki?"

- However Most Japanese Have Never Read It

- Japanese Attitudes toward Cleanliness

- Why Are Japanese Diligent?

- Portraying How Life Should be Led

- The World Largest Tomb of Emperor Nintoku

- Perceiving Nature as a Divine Manifestation

- A Harmonious Approach to Resolving Matters

- Other Interesting Episodes

- Disseminating the Kojiki Education in Japan

Read Kojiki to Understand Japan and Japanese

World's Longest Dynasty: Do you know that Japan is called "the only country in the world with a single dynasty"? This refers to the fact that there have been 126 generations of emperors, up to the present emperor, with one line of succession for 2,700 years. There is no such system in the world, and even the Roman Empire has a history of just over 1,000 years. I think you can see how rare this is. It is unclear if the emperors are actually connected for 126 consecutive generations without fail. At least from Emperor Jinmu, the first emperor, to the 25th emperor, we do not know for sure whether he actually existed or not. It is only from the 26th generation that we know with some degree of accuracy. In the beginning, it was the mythical world of "Kojiki". Even so, the fact that the lineage has continued for about 100 generations is astounding. That "Kojiki" is the oldest history book in Japan. It contains a lot of mythology, but it was very important in spreading the authority of the emperor to the world. By reading the Kojiki, you can understand, albeit dimly, the way Japanese people think and their customs. This book may be said to be the DNA of the Japanese people.

By Ryoji Shimada, staff writer

Tokyo won out as the venue for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic games. Japanese anime, manga and traditional culture continue to allure people outside Japan. On the other hand, the nuclear troubles in Fukushima are still making headlines. For better or worse, Japan continues to capture an increasing share of the world’s attention.

However, many people voice the opinion that Japan somehow seems quite different from other countries, making it more difficult to understand. Why, for example, did disaster sufferers or evacuees from the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami remain calm and generous toward others? Why is “omotenashi” (hospitality) or attentive customer service ubiquitous in Japan? Even a staff member at a convenience store greets customers politely and treats them with deference.

Some foreign visitors are surprised to see a security guard smile while directing traffic and even bow to pedestrians to apologize for keeping them waiting.

People who are interested in these phenomena are advised to read one of the oldest books about Japan. Kojiki, which in English is usually translated as “Record of Ancient Matters,” was completed in 712 C.E. Having reached its 1,300th anniversary last year spurred a revival in interest among Japanese. And even for Japanese themselves, the Kojiki is an eye-opener in that by reading it, one can discover the roots of Japan and the Japanese people.

Tsuneyasu Takeda, a writer and lecturer at Keio University, asserts, “Non-Japanese who read the Kojiki will discover what Japanese are all about. Even Japanese have sometimes become considerably detached from what they used to be, so for them it would be a good cognizance about the basics of being Japanese. For non-Japanese and Japanese alike, the Kojiki is one of the best sources for understanding the Japanese people.”

What Is "Kojiki?"

The Kojiki is the oldest extant chronicle in Japan. Compiled by Oh no Yasumaro at the request of Empress Gemmei, it is a collection of myths concerning the origin of the main islands of Japan, and various kami (deities or gods). Along with Nihon Shoki, another work that was completed in 720, the myths contained in the Kojiki are said to be part of the inspiration behind Shinto religious practices, including the misogi purification ritual.

A few English translations have been made of this chronicle. The first and probably best-known was completed in 1882 by Basil Hall Chamberlain, a professor of Japanese at Tokyo Imperial University (now University of Tokyo) and one of the foremost British Japanologists active in Japan in the late 19th century.

In the introduction to his translation, Chamberlain noted how valuable reading the Kojiki is for understanding the heart of Japan. He wrote:

“Of all the mass of Japanese literature, which lies before us as the result of nearly twelve centuries of book-making, the most important Monument is the work entitled ‘the Kojiki or ‘Records of Ancient Matters,’ which was completed in A.D. 712. It is the most important because it has preserved for us more faithfully than any other book the mythology, the manners, the language, and the traditional history of Ancient Japan.” He goes on to say customs seen now have roots in the Kojiki: “It is to these ‘Records’ and to a very small number of other ancient works, such as the poems of the ‘Collection of a Myriad Leaves’, that the investigator must look, if he would not at every step be misled in attributing originality to modern customs and ideas, which have simply been borrowed wholesale from the neighboring continent.”

In addition to being Japan’s oldest work of history, Kojiki also contains ancient Japanese mythology. As Takeda points out, “The Kojiki contains Japanese mythology as well as ancient history. The Kojiki, as the oldest history, notes how Japan was formed and founded and is also a collection of mythology, conveying the fundamentals of Japanese. It describes how Japanese think toward nature and what a beautiful way of life should be. You can enjoy reading the Kojiki from many different perspectives --- as a history textbook, a study on mythology or as an educational text.”

However Most Japanese Have Never Read It

Surprisingly enough, most Japanese never have a chance to read Kojiki. Norie Yoshiki, student at Keio University, Tokyo comments, “My father is from Shimane Prefecture where many myths originated, so I was familiar with some of the episodes in the Kojiki at an early age. But I didn’t read the Kojiki in its entirety until I was at university.”

Most schools in Japan never teach the story of the Kojiki. At a history class, teachers only mention the year when it was completed and its historical importance.

But Ms. Yoshiki, who was interested in Western culture, traveled to the U.S. to study at a Christian-affiliated high school. That’s when she was shocked at how differently Japanese think from Americans. “At the start of every meal, I would say, ‘Itadakimasu’ just like my American host family would say grace. They asked ‘what does it mean?’ and I replied, ‘we give thank to the foods that we are going to eat because we sacrifice them in order to sustain our lives.’ The family was astonished and told me that they are thankful to the God who gives them food, but never to the food itself.”

Yoshiki was also aware that all the students were knowledgeable about the Bible to some degree, and that many English expressions derived from or were influenced by the Bible. “I then noticed that we as Japanese have never been taught such a thing like the Bible. So I decided to learn the Kojiki after I got back to Japan,” she says.

What was her impression when she read it?

“I was taken aback,” she recalls. “I thought it is only about ancient matters, but it has relevance with the present. I felt so close to it. I supposed that its contents would have nothing to do with me, but things turned out to be completely opposite. In it, I discovered my roots as a Japanese.”

Japanese Attitudes toward Cleanliness

Why is it that Yoshiki thinks the Kojiki embodies the roots of Japanese? She found one reason in the Kojiki about the Japanese penchant for cleanliness.

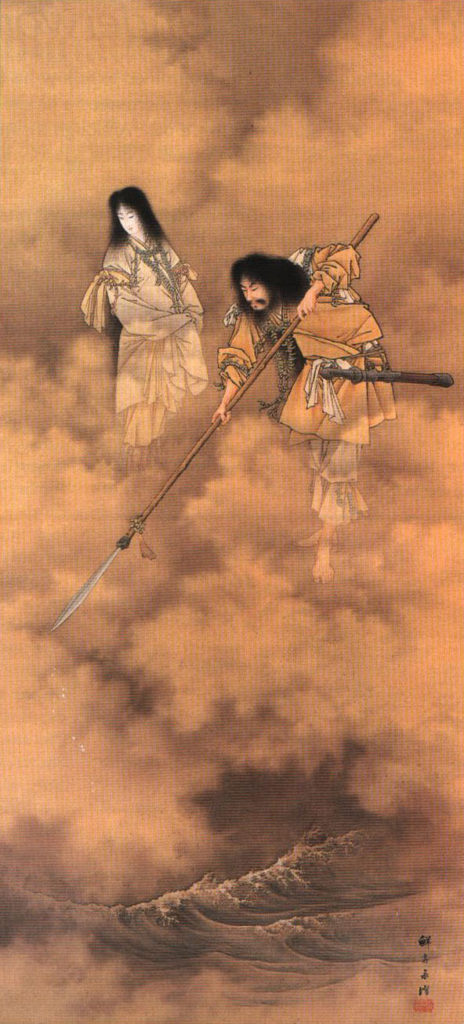

An important episode in the Kojiki tells the story of Izanagi-no-mikoto (Lord Izanagi) and his spouse and younger sister Izanami, who gave birth to the many islands of Japan and begot numerous kami (gods or deities). But Izanami died after giving birth to a god of fire. Afterwards, he paid his wife a visit in Yomi-no-kuni (the hereafter) in the hopes of reviving her, but failed. Upon his return from Yomi-no-kuni, after cleansing his body to remove impurities from the world, he begot various deities both good and evil, leading to the birth of the three most prominent: Amaterasu Omikami (the sun goddess) from his left eye; Tsukuyomi (the moon and night god) from his right eye; and Susanoo (tempest or storm god) from his nose.

This purification ritual, Yoshiki believes, influences the Japanese penchant for cleaning things up and bathing as part of their personal hygiene. When people go to a shrine to pray, they wash their hands and rinse out their mouths beforehand. Takeda points out that these activities represent a shortened form of purification.

The other history book, the Nihon Shoki, contains episodes for emperors to bathe in an onsen (hot bath) for healing. Yoshiki says, “I was aware that Japanese may be among the world’s most meticulous people about cleanliness. That’s why they like to bathe so much.”

Why Are Japanese Diligent?

Japanese are often regarded as hard working and diligent people. Yoshiki thinks the reasons can be also found in the Kojiki. “In the Kojiki, Amaterasu Omikami has a job of weaving silk. Even the most revered deity has an occupation. Even for a god, a job is a part of the daily life. It is common sense to have a job.”

By the same token, the Kojiki notes that various gods are assigned tasks to perform. For example, Hoori, also known as Hikohohodemi no Mikoto, is a hunter in the mountains and his younger brother Hoderi is a fisherman.

Portraying How Life Should be Led

Numerous episodes in the Kojiki beautifully portray the essence of an ideal life or how life should be led. Taken in context of Takeda’s previous comment, it serves, in a sense, as an educational textbook. Take, for example, the famous tale of the Inaba no Shiro Usagi (White Hare of Inaba). In it, Ohkuninushi no Mikoto (a son of Susanoo, one of the three prominent gods, was previously known as just Ohnamuji without the honorific name) and his many brothers were all suitors for the hand in marriage of Princess Yakami of the region known as Inaba (around present-day Tottori Prefecture). They all traveled together from their home in Izumo (around present-day Shimane Prefecture) to neighboring Inaba to court her.

Along the way, the brothers encounter a poor little hare, flayed and raw-skinned, lying in agony upon a sea shore. The group asks what happened, and the white hare explains that a crocodile (wani, interpreted as a mythological creature based on a shark) had torn off its fur.

The gods who listened to the hare were cruel-hearted, and as a prank, instructed the hare to wash himself in salty sea water and blow himself dry in the wind. The salt water of course, put the hare in much more stinging pain than before. Then came along Ohnamuji lagging behind. The gentle-hearted god told the hare to go to the river and wash himself in the fresh water, then gather the flowering spikes of cattail plants growing all around, and scatter the catkins on the ground and roll over them until covered with fleece. The cured hare, in gratitude, divined a prediction that Ohnamuji would be the one to win the hand of Princess Yakami. And sure enough the hare’s prediction came true and he became the ruler of the region.

Thus the life led by Ohnamuji was beautifully depicted. This episode can be used for moral education and it is easy to think that it influences Japanese people’s view toward life.

The World Largest Tomb of Emperor Nintoku

Asked about what episode Takeda would like non-Japanese to know, he names a similar episode about the Emperor Nintoku. The 16th Emperor, Nintoku became the role model for other Emperors because of his intelligence and well-balanced thinking. He was believed to have reigned during the late 4th century to early 5th century.

A famous episode tells that during his reign, Nintoku concluded that since no smoke could be seen rising throughout the land, the country must be poverty-stricken. He then halted all taxes and conscript labor for the next three years. While his great palace became ramshackle and the rain leaked in from holes in the roof, no repairs were made. Even after people became affluent and they were willing to pay taxes, the Emperor refused. After three more years, the palace became so dilapidated the people took the initiative to refurbish the palace. Emperor Nintoku told his empress, “Heaven sent us to the earth as the monarch for its people. As the monarch he exists for his people’s sake. If just one of them is famished, the monarch is to be blamed for it.” Daisen-Kofun in Sakai, Osaka Prefecture is considered to be his final resting place.

From the above episode, Takeda believes the Emperor’s way of thinking describes an obligation to care for others, which is beautiful and ingrained in Japanese people’s mindset.

“After the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami, the evacuees endured patiently and still demonstrated generosity toward others,” he says. “This comportment surprised the world outside.”

He also derives the relationship between the people and the Emperor from this episode. “The Emperors reside for the people. The people revere the Emperor just like their forefathers and support the Emperor’s reign. The Emperor does not govern the country through military force, but through his commitment to the people, which the people reciprocate by supporting the reign. This is what sustains the national polity.”

Perceiving Nature as a Divine Manifestation

The word “yaoyorozu” in Japanese literally means eight million but is used euphemistically to mean “a large number” of something. It is often said that Japan is a country of yaoyorozu no kami (gods). In the Kojiki, a variety of gods are mentioned: gods of fire, mountains, sea, house, kitchen, and many others.

![Izumo Taisha and its gigantic shimenawa[1]](https://manabink.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/image-45-1.jpg)

Takeda says, “We Japanese see the presence of gods in the greatness of nature. We treasure everything around us. We sometimes put the honorific ‘o’ before nouns like ‘o-mizu’ (water) or ‘o-hana’ (flowers) to express our appreciation. No such usage can be found in English or other Western languages.

“The Western ideal is for man to preside over nature on behalf of the God. But Japanese think they are permitted to live through nature’s bounty, and therefore tend to act rather modestly toward all things. The Kojiki contains no accounts of extravagant living.”

A Harmonious Approach to Resolving Matters

Japanese are often said to place importance on “wa” (harmony). They try to avoid conflicts as much as possible. An important episode in the Kojiki demonstrates solving a problem through dialogue.

According to the Kojiki, when Ninigi-no-Mikoto, a grandson of Amaterasu, descended from the heavens, the god Ohkuninushi granted him control of his country through dialogues instead of fighting a major battle. Pleased by this action, Amaterasu agreed to present the Izumo-taisha (the Grand Shrine of Izumo, one of the most ancient and important Shinto shrines in Japan) to Ohkuninushi at his request. Until then, he had devoted himself to building the nation with the help of other gods.

Takeda thinks this salient event is one of the causes why Japanese place a high importance on harmony.

Other Interesting Episodes

For Yoshiki, the Kojiki contains many other episodes that she finds interesting. Her French friend found an interesting episode about the Eastward Progression by the first emperor Jimmu and his elder brother.

An artwork of Emperor Jimmu with his emblematic long bow and an accompanying wild bird by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Yoshiki found the unique viewpoint of the Kojiki and says, “Amaterasu is the goddess of the sun and probably the most revered in Japan. In Greek mythology by contrast, it is Zeus that’s the most important god, rather than Apollo, the god of the sun.”

In the account of the battle during the Eastward Progression, Jimmu’s brother was wounded and said, “It is not right for me, an august child of the Sun-Deity, to fight facing the sun. It is for this reason that I was stricken by the wretched villain’s hurtful hand. I will henceforward turn round, and smite him with my back to the sun.”

Yoshiki also points out the episode of the gods Izanagi and his wife Izanami, who were assigned the task of forming the islands that would become the Japanese archipelago. This is an episode that suggests when dating, a man should always be the one to invite the woman. Since Izanami (Izanagi’s wife) was the first to speak, saying: “Oh, indeed you are a beautiful and kind youth!” to which Izanagi replied: “Oh, what a most beautiful and kind youth!”

Izanagi then rebuked Izanami by saying: “It is wrong for the wife to speak first.” However they mated anyway and later produced two children, neither of whom was considered legitimate. The two deities ascended forthwith to heaven and inquired of the heavenly deities. They were advised “The children were not legitimate because the female spoke first. Descend back to the earth again and amend your words.” They returned and this time with Izanagi the first to speak, and successfully gave birth to many islands.

Disseminating the Kojiki Education in Japan

Yoshiki is intrigued by the Kojiki but all the more so, feels disturbed by the fact that her generation knows so little about it.

“Many members of my generation are adrift and don’t know what to do,” she says. “They seem to be spineless. If they become better aware of their Japanese roots, they could become stronger and brighter.”

She goes on to say, “Arnold Toynbee, the famous British historian, once wrote something to the effect that ‘Unless one learns one’s own mythology before junior high school, the race perishes without exception.’ I feel the young generation of Japan must study our mythology.”

Takeda, in accord with her thinking said, “I was puzzled in my early years why the Old and New Testament of the Bible, or a book of Buddhist sutras, would be placed in hotel rooms in Japan instead of the Kojiki. But why not the Kojiki?”

Last year, Takeda and his group solicited donations and published an easy-to-comprehend version of the Kojiki although in more than 200 pages, which was distributed free of charge to hotels that were willing to place copies in their guest rooms.

“We distributed 14,500 copies last year to commemorate the Kojiki’s 1,300th anniversary,” he says. “The hotels were all happy since they received positive comments from their guests. We even received phone calls from some guests directly, and they raved about it.”

Copies of the Kojiki were also distributed to all the schools in Tokyo, which number several thousands in total. Takeda is now planning a second printing in response to strong demand.

Hayao Kawai, a Japanese Jungian psychologist who has been described as “the founder of Japanese analytical and clinical psychology,” researched and studied the Kojiki and numerous old Japanese stories and legends. He found that most tend to emphasize a beautiful way of life rather than simply rewarding good and punishing evil, a theme commonly found in the West. The Kojiki also contains many beautiful poems by deities or Emperors.

Those who truly want to understand Japan and the Japanese people should read this monumental work. Although written 1,300 years ago, it still resonates in the hearts and minds of Japanese people today.

[1] Shimenawa are sacred cords made of twisted strands of rice straw. They are believed to have the special power to ward off evil spirits or sickness. They are sometimes hung from torii (the entrance gates of shrines) or before the altars of Shinto shrines, and also around trees or rocks considered to be places of the divine. It is also common to find shimenawa over doorways of houses or on the front of cars at New Years.

One thought on “Kojiki: the Oldest History Book in Japan”