Sense of Privacy of Japanese People

CONTENTS

Japanese people don't want to stand out

There are many myths about Japan and Japanese contemporary culture but one certainty is that “standing out” is still frowned upon. So perhaps it is not surprising that when you ask people about the nature of privacy and their concerns about it given that today’s prevalence of social media it seems inevitable that Japanese people do indeed seem more conservative and more concerned than those in other nations.

There Is No Global Common Sense About Privacy

To understand those differences, we recently undertook a global study across 17 nations looking at the Truth about Privacy. The study involved in-depth discussions with people of all groups from 15 to 60 and in six nations including Japan, a detailed internet survey of 1,000 respondents. The results clearly indicate that privacy is not the same anymore, anywhere. We are living in a world with new privacy norms. Driven by factors like the all pervasive nature of technology, the increased openness of celebrity culture, and the subsequent “end of embarrassment” all revolving around the nature of social networking as a constant in normal life. It is affecting the way we deal with our communities, our friends and our work.

Globally we found that people who do not participate in social media now feel a need to defend this decision because it is now seen as “unusual” not to do so. That was certainly the casein Japan where the great majority of people have been using semi-smartphones with SNS and blogger soft ware for a decade. A few years ago Japanese became the most common blogging language in the world, according to Digerati one third of all blogs were written in Japanese, slightly higher than English. Why? Because unlike mobile phones elsewhere the majority of Japanese people had phones that allowed them to blog on the run. Hence their blog entries were and are much shorter and much more about brief comments on what they were doing “right now” rather than blogs in the West, which tended to be longer and more about points of view. In the last three years smartphones and the rise of Twitter have seen the rest of the world fall into a format of “personally sharing” that is similar to that initially launched in Japan. And of course it is part of the reason Japanese people have so quickly migrated to Twitter.

Meanwhile the majority people around the world have found new ways to indulge their nosiness: l 4 in 10 people have looked at online photos of people they hardly know.(slightly less in Japan ) A third have googled people they hardly know to find out personal details. (slightly less in Japan ) A quarter have read a friend/partner’s text messages. (slightly more in Japan ) 1 in 10 are reading someone’s diary and that is just the people who admit to it. (slightly less in Japan ).

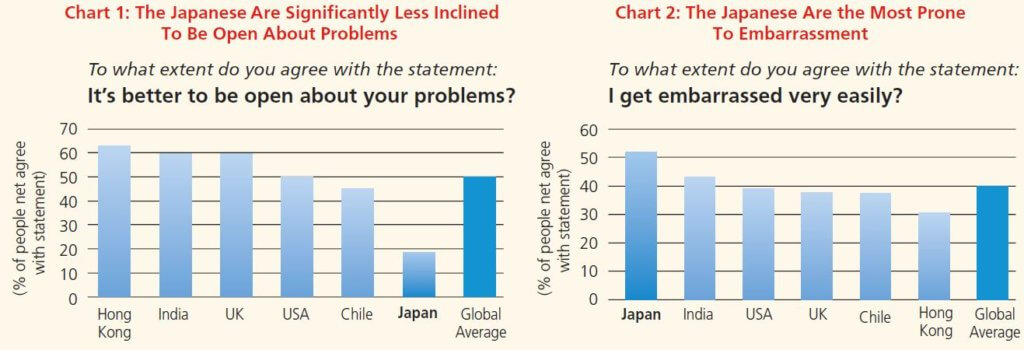

Developing countries more open to sharing

What are some of the significant differences between Japan and the rest of the world? It was very clear from the Truth about Privacy research that while concerns are universal we can see a distinct pattern where “southern” or more developing countries like India and Chile are more open to sharing, and “northern” developed markets like the USA and UK are much less open. And interestingly Japan is the least open. Chart 1 clearly shows that while over 50% of people around the world generally agree that “it’s better to be open about your problems,” less than 20% in Japan agree. Again when we asked to what extent people agree sharing their thoughts and opinions, while the global average answer was near 60%, only 30% of Japanese respondents agreed.

Japanese Don’t Like to Expose Themselves Online

One significant reason for this reticence might be social pressure to “not standout” but clearly connected to that was a belief that people in Japan get embarrassed easily. As Chart 2 points out, over 50% of Japanese respondents agreed on that notion, a full 10 points more than the global average. The truth is that Japanese people just do not seem as motivated to share online as others. Globally around a quarter of people agree that if they share more personal information online, they will get ahead in their career. In countries like India and Chile that figure rose to over 40%. However in Japan only 10% of people believed that to be true.

As we saw above, Japanese people do seem just less nosey. When we asked, “if you had access to all information about anyone and anything,” we found that while globally 30% of people said nothing (as in they would not use that access to seek out private details of other people) nearly 40% of Japanese made that their first choice of action. However when it came to all “my governments secret files” while this was the second most popular answer everywhere at 23%, nearly 30% of Japanese agreed that would be their first use of open access to all data. Of course the fact our survey was completed 4 months after the disasters of 3.11 and the subsequent public unhappiness with the government’s reactions to disaster relief and the nuclear reactor situation no doubt made such interest topical.

Equally interesting was that on many measures of inquisitiveness Japanese people just report a lower interest compared to other countries. Would they like the names of everyone their partner has had relationships with? Would they like to know the salaries of everyone in their company? Would they like access to all the emails and text messages of their favorite celebrity? In each case their interest was two thirds the global level.

“Personal Information” Protection Law in Japan

Perhaps three issues are driving the attitude to privacy in Japan: 1 People have become more wary of “privacy” as an issue as opposed to something that was taken for granted since the introduction of the “Personal Information” Protection Law was put into effect in 2005. Since then companies have been educating workers to maintain persona information to control risks, as a result heightening the awareness, and concern over privacy of information. Previously Japan had always been a community-centered society and information was naturally shared among people, so the concept of “privacy” as in keeping information was not as much of a concern. 2 Everyone wants to decide themselves whether something is beneficial to them or not, and wants to provide information only if it is beneficial to them. Therefore, they show a strong sense of disgust when something they do not want is put into their face by a company/brand. However, if they see a clear benefit, they can bear such actions. For example, people do not mind receiving mobile messages from McDonald’s because they get a discount. 3 Brands with a strong image of stability and social contribution had a stronger image of being able to protect privacy. In other words, if a company/brand is trusted in existing marketing contexts, people have a more positive image about protection toward privacy. Perhaps not surprising that over 70% of people said that banks and financial institutions were the business category they trusted most in terms of privacy.

SNS is least trusted

It is also interesting that globally people believe the institutions they can least trust at the moment are social network sites. There is a clear concern that Facebook, Twitter, etc are not really capable of providing real security and that because of all the data they now collect they need to prove their ability not to threaten members’ long term privacy. That applied as strongly in Japan as elsewhere. The real truth is that many people around the world, but especially in Japan told us that they would prefer to be able to use their favorite social networking site without having to expose their real identity. The propensity for Japanese people to like using sites such as Mix where they do not have to reveal their real names etc. is usually, because they believe they can be more honest in their relative anonymity. That is after all what privacy often means to people. The ability to just keep things to yourself and not be pointed at, sounds like yet another Japanese “myth” that is actually true.