SDGs in Japan: Japan’s wise investment in people

CONTENTS

ARI: Training Local Leaders from Emerging Nations to Create a Peaceful and Sustainable World

By Ryoji Shimada, staff writer

“In my community, people earn a living through agriculture, fishing and livestock breeding. Some of their biggest obstacles to sustainability include limited knowledge and insufficient time to focus on future plans. I want to receive agricultural training so I can serve as a resource for farmers in my community.” Act Ka Hti, a community health worker from Pathein Myaung Mya Association in Myanmar, expresses her hope during the study at the Asian Rural Institute (ARI).

Juliao Nunes Jose, leader of a farmers’ from the Rafaela East Timor Fund in East Timor, also voices his hopes. “East Timor is an agricultural nation, and unless we can become self-sufficient in agriculture we cannot survive. The main things I want to learn at ARI are sustainable techniques for enriching the soil, proper cultivation of crops, and how to raise livestock naturally.”

ARI, nestled on a rural hillside, is situated three hours north of Tokyo by train at Nasushiobara, Tochigi Prefecture. As a training school, it’s unlike any others in Japan. “What makes ARI unique? It’s a community based, multi-cultural, multi-racial training center for grassroots-level people,” says 86-year-old Toshihiro Takami, ARI’s founder. Or, to quote from the words of its brochure, “It is a practical school for attaining a fair and peaceful society with an understanding of differences between nations, religions, races, customs, values, etc.”

Every year, some 30 rural community leaders from so-called Emerging World across Asia, Africa and the Pacific gather at ARI for a nine-month live-in program to acquire the skills for community self-help and development. The persons mentioned above were some of the participants during 2012.

Since its inception in 1973, ARI has returned more than 1,200 graduates to their home communities.

Organic Farming for Self-help

What, specifically, do students learn at ARI? As you can infer from the above participants’ expectations, the institution provides roughly two main pillars: “organic farming” and “community building.” Most of the participants come from rural districts in developing countries and their communities’ economic roots are based largely on agriculture, which is essential for their survival and development. But their livelihoods are riddled with difficulties. For one thing, pesticides, herbicides and chemical fertilizers --- those tools of the so-called Green Revolution --- have trapped some farmers in market forces over which they have little control.

John Nyondo, a graduate of ARI from Zambia, says, “Big companies have a lot of influence on the government and whatever their experts at research and agriculture institutions tell them to do, they will develop a curriculum along those lines, using a lot of chemical fertilizers. Since our country became independent, our farmers have been using chemicals. But now crop yield has been going down dramatically and the prices for chemical fertilizers are going up.”

Repeated use of such chemicals is widely believed to harden the soil and render the land unproductive.

“Chemical fertilizer is so expensive, so because of that the farmers are not able to buy it,” another graduate, Liberia’s Patrick Asumana, complains. “Sometimes you have four or five farmers pool their funds to buy just one bag, and how much of that can you use?”

To overcome these problems, organic or natural farming is very much a key and that’s what most of the trainees want to learn at ARI. It is also an important aspect for environmental sustainability and continual development.

What makes organic farming so important? First of all, the keys to successful organic farming involve building up the soil with organic fertilizers like bokashi[1] compost which is made by a traditional Japanese method. Minced vegetable matter mixed with sugar is made into fermented plant juice. Used together with decomposed animal waste, the product is highly concentrated natural organic fertilizer, eliminating the need for chemicals. Many methods for farming free from chemical pesticides exist. From wood or bamboo charcoal making, wood vinegar is retrieved, which finds use as a pesticide. They also learn how to use ducks and certain special fish to remove weeds and insects from rice paddies. In this way, they don’t need to reply on chemicals for growth and maintenance.

[1] Bokashi is a method that uses a mix of microorganisms to cover food waste to decrease smell. It derives from the practice of Japanese farmers centuries ago of covering food waste with rich, local soil that contained the microorganisms that would ferment the waste. After a few weeks, they would bury the waste which, several weeks later, would become soil itself.

Amino acid from fish as fertilizer; rice-duck farming; indigenous microorganisms; soil block for seedlings; and so on. The list of organic farming techniques they learn goes on and on. Organic farming may appear to be low-tech, but integrating the cycle of needs with the capacity of plants, animals and humans is a complex and sophisticated undertaking.

“I think this is highly scientific, you know compost making, organic farming, and enriching the soil while producing food at the same time. This kind of agriculture calls for a highly sophisticated understanding of the entire world,” says Takafumi.

It is also worth noting that students try to avoid use of machines. The bulk of ARI farm work, such as planting rice seedlings, is done by hand. Since the situations of each community where participants come from may vary, machinery availability also differs. Becoming able to farm without machinery, they can adapt to any situation.

Surprisingly, during the nine-month training session at ARI, the students harvest most of their own food.

“We talk about self-sufficiency. Because it’s one of the things in which we hope to train people. So they don’t need to look to somebody else to solve their problems,” Tomoko Arakawa, General Manager at ARI, explains. “And that’s one of the reasons why we raise around 90% of our own food to prove that its people can do that kind of thing.” However not all farm work is performed without machinery. Providing food sufficiency for a community of 70 plus persons requires a lot of land under cultivation. Four tons a year rice alone, for instance, that does require machinery.

Catering to Their Own Needs

Not all studies take place on the farmland. The students also study indoors at classroom lectures, which include such subjects as the concept of sustainable agriculture, feed management, natural farming in tropical areas, permaculture, agroforestry and alternative marketing systems, among others.

In addition, trainees are able to experiment with production techniques that work best in their own home environment. “I wanted to do a small research with these broiler fowl. I wanted to try with food available in Sri Lanka,” says Walter Silva. “Here I try with four pens. I give them four kinds of feed. I try other pens with soya beans that are available in Sri Lanka and some rice bran. Most of the people buy commercial feed, but I can make feed myself cheaply this way.”

Maximo Alverez’s project was to discover how biogas from animal waste may provide fuels for villagers in the Philippines. “There’s an inlet here, where we put the materials --- pig manure, chicken manure and cow dung. You just put them here and wait for them to decompose and produce gas.” He explains with a smile. “It’s so simple, and people can build it themselves.”

Other participants discover how to turn used cooking oil into clean burning bio diesel vehicle fuel. Still others have experimented with traditional well-drilling techniques to provide water for their home villages. Or learned to generate electricity using a windmill constructed from old bicycle parts. Arakawa says, “They can’t experiment with everybody’s produce since a failure would result in a bad harvest or nothing. But with these individual experiments, they can use their creativity. That’s one of the important things that they can gain here. They are encouraged to open up their minds to the whole world and what might be possible.”

Cemented by Extracurricular Activities

ARI students also embark on many observation trips and study tours to bolster their training. To deepen understanding of various agricultural and environmental issues, they make short observation trips to nearby cities and prefectures. Their visits included a study of the Nasu Aqueduct, which was developed 130 years ago by local people and farmers for agricultural use, and the Ashio Copper Mine, a notorious historical site of environmental destruction in the late 19th and early 20th century. The mine was opposed by Shozo Tanaka, a much-respected politician and pioneer in Japan’s environmental movement, who fought for the livelihoods of the suffering people and the environment.

During the summer term, participants have a chance to study a rural Japanese community by visiting various places and organizations, such as organic farms and farming associations, consumer co-ops, Japan Agriculture (JA), research institutions, and others.

Another type of tour focuses on urban issues and social welfare. Through these visits, participants learn how Japan deals with various social issues. Participants are also able to visit such places as Hamamatsu Seirei Social Welfare Community, which cares for the elderly and physically and mentally disabled and the Hiroshima Peace Park to study peace issues.

These extracurricular activities supplement the nine-month training course and the students’ perspectives are broadened.

Building Community

Building a good community is important in every society and especially so for rural areas’ survival. Imagine, for example, the work of rice planting, or corn and rice harvesting, without the use of machines. Such big jobs need the involvement of the entire community. So building a good community is essential and is another pillar of training at ARI.

The ARI community is composed of participants in the training program, training assistants, graduate interns, volunteers and staff members and their families, as well as part-time workers, lecturers and others. The members of this diverse community live together on or very near the campus and each one is involved in the whole work of the school and farm. From the growing and harvesting of food to its cooking and eating or cleaning toilets in the morning, there are many daily tasks. Through living together they have constant learning opportunities.

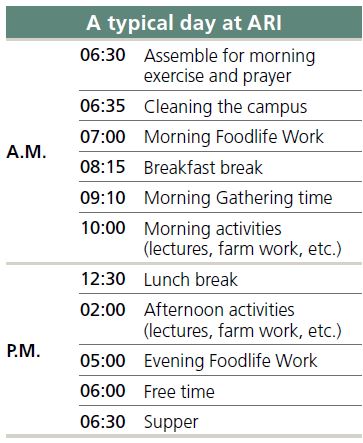

For instance, around 30 participants are divided into four groups. Each group is given management responsibility in cultivated fields and in livestock (fish, pigs, poultry), with the support of staff and volunteers. Each participant in the group takes turns to become a leader so they can learn qualities of good leadership. The day at ARI begins early. Staff, volunteers, participants and working visitors perform 6:30 am morning exercises followed by cleanup chores and farm work before partaking breakfast. ARI calls this Foodlife Wor and the process is repeated each afternoon.

But bringing together people with fundamentally different cultural, ethnic and religious backgrounds is no easy task. Thomas Itsuo Fujishima, a public relations staff member at ARI, says, “There are certainly struggles, misunderstandings, and miscommunications, especially at the beginning.” English serves as ARI’s lingua franca, but for almost everybody it’s their second, if not third, or fourth, language. Especially when discussing or disagreeing on important issues, good communications are necessary to avoid friction. Many participants say that the most difficult aspect of the course is how to communicate with others, because every speaker speaks English with his or her own accent and mutual understanding can be difficult.

But differences are not necessarily bad. In other words, they can make diversity enjoyable and broaden people’s horizons. Chom Boonrahong, a graduate from Thailand says, “At ARI the people came from many countries, many different cultures, some Muslim, some Buddhist, some Christian. It means everyone has a different background and different concept; but we have to make that an opportunity to learn from each other. That is the concept and the practice from ARI to make me aware more when I run our organization. I have to work with our team to be like one family, to work together, and learn together.”

Fujishima is in agreement. “It is our motto that we live together no matter what,” he says. “We have to find some way, some compromise to unify our spirits. Through living together, we have to face our differences and grow together. And at the end of the nine months, we always see there is a miracle that indeed we care and respect each other.” He gave the example of two Sri Lankan participants, one who was Sinhalese and the other a Tamil. Initially they were at odds with each other due to historical tensions between Sri Lanka’s two different ethnic groups. But in the end the two came to terms and developed mutual respect.

“In the end we see differences on a personal level --- not according to nationality, race or religion. At first, you see black people or encounter unfamiliar religions and think they are different. But after a while you see some common ground as human beings and find that those differences are superficial, like the clothes one wears. Through common tasks in living together or shared goals of producing our own food or completing this training, they build close friendship over those differences. That’s natural,” observes Fujishima.

There are also monthly community events as well as fellowship opportunities with local schools. One specific example is a two-day Harvest Thanksgiving Celebration during the rice harvest (on the second Saturday and Sunday of October), which last year drew over 1,500 visitors from neighboring towns. The participants organize a special culture show and make dishes from various nations using their organic produce, and showcase handicrafts, songs and dance from the students’ countries in stage performances and a fundraising bazaar. These events are prepared with the students in mind, and are an integral part of their ARI training program.

ARI believes that everyone finds some sense of belonging there and that people’s diversity and differences, when respected, can create a dynamic life together.

Supported by Volunteers

What keeps ARI going? Certainly it has the vision and commitment of its hard-working and dedicated staff. But also it owes thanks to the contributions of volunteers, who serve as one of the various constituents at ARI. Many of them are local laypeople who believe in ARI’s mission. Some are young Japanese students wanting to experience the life and vitality of an international community in their midst. But others come from farther afield, lending their talents to the multitude of tasks that need to be done.

Douglas Knight, who came together with his wife from the U.S., says, “I was interested in global issues like environment or social justice and wanted to do some volunteer work.” He was also interested in farming, so he was recommended to ARI through his local church. Asked how he found ARI, he says, “It is incredible. I have read and studied in college a few ideas connected with organic farming and mainly studied a lot of how industrial agriculture is not good for the environment and all of the changes it causes to the environment and how it affects the natural cycle in an eco-system. Then I came here, looking at this farming model, thinking about the ecology and environment then connected it with what I know about industrial agriculture, and everything became very clear, very quickly.

“I was immediately very impressed with what was going on here and knew this was something I wanted to pursue for the rest of my life. By coming here, we are able to see this entire system, this entire food system, food eco-system. We are able to participate in it and become part of it and see all these possibilities taking place and things actually happening. It is quite a different experience than just studying or reading or talking with other students about it.”

Sakura Ohmuro from Hiroshima, Japan, working as assistant on the farmland, says “I wanted to put myself in an intercultural environment and learn something from it.” She goes on to talk about what she has learned, “I find that personality is important. For example, let’s say there are two participants from the same country, same religion, same race, but I can get along well with only one of the two. Or sometimes I can be a good friend with someone whose language I don’t understand. On the other hand, with some people I can’t make friends even though I understand what they say.”

Jeannine Hollaus, also from the U.S., says with a smile, “My school, Wellesley College, has a list of internships from which you can choose and apply. And ARI was one of the most unconventional of them all. Because, you know, the work is quite tough, but the community makes it all worth the effort. You do it as a community, you share your great experiences, you share the work, you share the food, you share life.”

Each year ARI plays host to more than 100 working visitors. Some come on their own and others are part of organized work groups. All are paying their own way to participate in this unique and vital ecumenical mission. Indeed, it’s financial support by a whole family of global colleagues that enables ARI each year to welcome a new group of participants.

“Over 80% depend upon our scholarship funding which we raise from supporters, and only 20% or less from the sending organizations,” says Takami. “We always have to scrape for funds.” The cost for each participant to receive training in a nine-month program, is about 1,600,000 yen ($17,777) plus an average of 250,000 yen ($2,777) for round-trip transportation to and from Japan. Most of the operation costs come from donations.

Impact Greater Than the Mere Numbers

As of 2013, the number of total graduates from ARI is just over 1,200. But if the abovementioned volunteers are included, the number would more than double. ARI also regularly accepts Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers for their advance training. They are later dispatched by JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) to developing countries. Besides that, it can be assumed that graduates are already community leaders in their home countries who can guide and influence a great many others.

Billian Nyukighan Njodzeka, a 2002 graduate from Cameroon, is a good example. She is quoted as saying in the report on the ARI webpage, “Since my return from ARI, I have been able to use the skills and knowledge I gained there to build up my organization, Strategic Humanitarian Services (SHUMAS) and improve the production capacity of peasant farmers. We have set up a micro credit and micro enterprise scheme benefiting more than 6,000 peasant women in Cameroon. We also started a pilot organic farming scheme which is called the SHUMAS Integrated Organic Farming and Demonstration Center. Our target is to provide short and long term courses on organic and alternative farming to 2,000 farmers each year.” Her organization also completed eight gravity fed water systems from spring catchments that provide water to over 50,000 people.

Many other graduates, after going back to their homeland, set up their own organizations to teach others organic farming techniques and help in their communities’ development. Each year, ARI receives more applications than the 30 who can be accommodated. Yet even with this small number, the impact they will exert on the future is immeasurable. ARI founder Takami has a firm belief: “We are investing in people who will dedicate their whole life to sustaining life in the future. I think it’s a wise investment, and a lasting investment, in people who will work as leaders.”

Mission & History of Asian Rural Institute

The mission of the Asian Rural Institute is to build an environmentally healthy, just and peaceful world, in which each person can live to his or her fullest potential. To carry out this mission, rural leaders are nurtured and trained for a life of sharing. Leaders, both women and men, who live and work in grassroots rural communities primarily in Asia, Africa and the Pacific, form a community of learning each year together with staff and other residents. Through community-based learning they study the best ways for rural people to share and enhance resources and abilities for the common good. They present a challenge to themselves and to the whole world in their approach to food and life.

ARI seeks local leaders who have demonstrated through their actions their commitment to serve their people and act as conduits for positive change within their own communities. The applicants come from diverse fields: agricultural trainers, community and village leaders, church leaders, NGO personnel, teachers, orphanage staff, and so on. The qualifications of applicants are not demanding as long as they are willing to share in ARI’s vision.

--A Brief History--

ARI was established in its present location in 1973 based on the Southeast Asia Christian Rural Leaders Training Course at Theological Seminary for Rural Mission in Machida, Tokyo. It started as an international organization training leaders who engage in rural development in developing countries, to satisfy the demand for training by Christian churches and groups that had already taken part in rural development in Southeast Asian countries. The foundation was supported by Japanese, European and American Christian churches and other groups. Since 1996, ARI has also accepted Japanese participants who intend to serve rural communities in the future – either in Japan or in other countries.

-300x200.jpg)