About Japanese Youth Profile: Lost Confidence

CONTENTS

- Pervading Sense of Being Blocked

- Aging Population with a Low Birth Rate

- Evils of Relaxed Education

- “Galapagos Culture” of Young People

- Mobile-phone Culture (Galapagos-phone Culture) vs. Computer Culture or Smartphone Culture

- Putting Their Effort into Building a Village Society

- They Know the Reality of Where They Stand

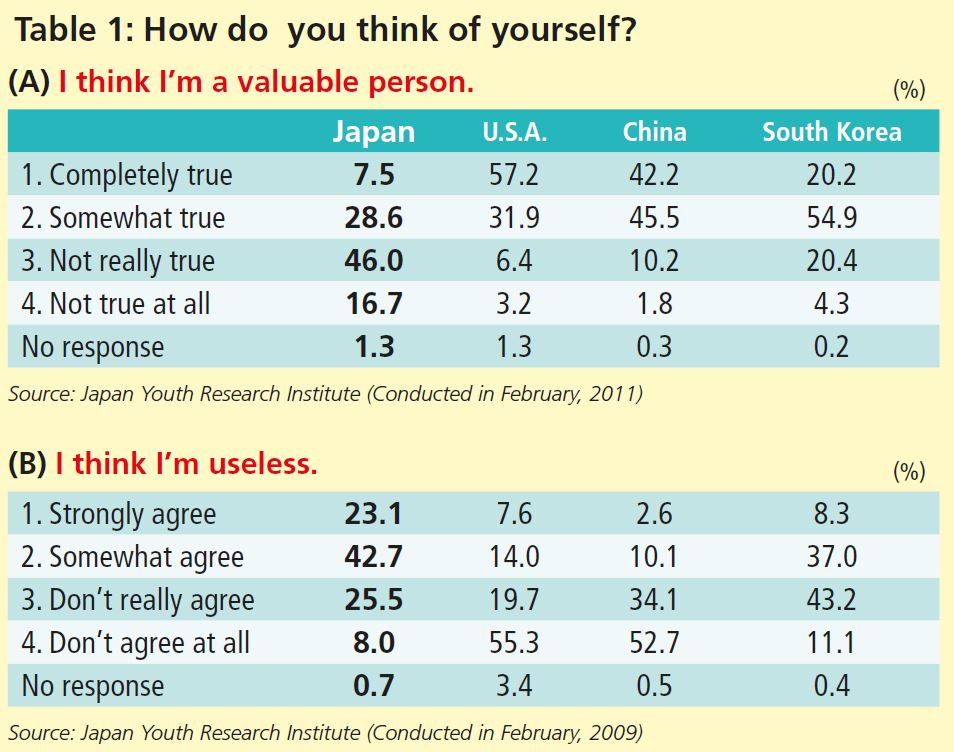

I think I’m a valuable person: Japan 7.5%, U.S.A. 57.2%, China 42.2%, South Korea 20.2%

I evaluate myself positively: Japan 6.2%, U.S.A. 41.2%, China 38.0%, South Korea 18.9%

I am satisfied with myself: Japan 3.9%, U.S.A. 41.6%, China 21.9%, South Korea 14.9%

I think I’m excellent: Japan 4.3%, U.S.A. 58.3%, China 25.7%, South Korea 10.3%

These are the results of a survey, carried out in February of this year, of the attitude of high school students in Japan, the U.S.A., China and South Korea. Of the four countries, Japanese students overwhelmingly had the lowest scores. Why are Japanese students so lacking in confidence?

Of course, the results of a survey like this easily reveal national characteristics. In general, in countries like the U.S. and China, where self-assertion is a strong part of the national identity, it was easy to get a large number of responses to an extreme option such as “completely true,” while on the other hand, in a country like Japan with a more ambiguous national identity, it was easy to get a large number of responses to a moderate option such as “somewhat true.”

That being said, although the questions were different, if we look at the results (below) of the same kind of survey two years ago in February 2009, the exceedingly low confidence of Japanese high school students stands out sharply. Considering this, we cannot blame only our national character.

Japan’s extended economic slump of the 1990s and 2000s is known as the “lost 20 years.” Having lived through this negative era, along with the rapidly changing period of the rise of the Internet, what is the mentality of today’s young people? And why has such a lack of confidence surfaced?

Pervading Sense of Being Blocked

The first possible reason is the sense of being blocked, caused by the economic slump mentioned above, that has surrounded Japan for too long.

In the 1980s, as Japanese cars gained fans due to their fuel-efficiency, American automakers were hit hard. Violent displays in the U.S., such as the Rising Sun flag being burned or Japanese passenger cars being smashed with hammers, were widely taken up by the Japanese media.

This was the so-called “Japan-bashing” of the 1980s. But for Japanese of that era, for whom memories of defeat in war still remained, there is no doubt that a major power like the U.S. becoming aware of Japan to such a degree was also connected in a way to pride and self-confidence of Japanese people.

After that came the bubble economy (commonly accepted to be roughly the four years and three months [51 months] from December 1986 to February 1992) and its collapse. Then we plunged into the “lost 20 years.” The deflationary economy continued, and then there was the 2008 financial crisis. “Japan-bashing” was replaced by “Japan-passing” and then “Japan nothing.”

Come to think of it, today’s high school students (born between 1993 and 1995) only have experience of these post-bubble “Japan-passing” and “Japan nothing” eras. In 2010 there were 31,690 suicides in Japan, which means that, very sadly, the number exceeded 30,000 people for the 13th year in a row. Today’s high school students’ lives have coincided with this period of increasing suicides in Japan. This can also be said to be emblematic of this era.

On the one hand, since the 1990s, the U.S.’s former “Pax Americana” influence as a superpower has been fading. But because there is no doubt that they still boasted the number one presence in the world and have produced many young global start-ups such as Google and Facebook, there still exists an environment in which young people can easily dream, “Maybe that could be me.”

China is in the midst of a period of very high growth. With a 2010 GDP 10.3% higher than the previous year, China took over the position of “world’s second-largest economy” that Japan had been defending desperately since 1968. China also had the Beijing Olympics and the Shanghai World’s Fair, and although the problem of inequality is incomparably worse than Japan’s, in Japan the situation is reversed, with the elderly having the money while young people are suffering economically. It is a trend in many emerging economies where there is significant development - young people have higher education, and more money than their elders, so it is easy for them to be optimistic. Also, as in the U.S., China’s young talent is steadily venturing out into the world, represented by entrepreneurs - especially those in IT, as well as best-selling authors such as Han Han, world-class pianists such as Lang Lang, and athletes such as the National Basketball Association’s Yao Ming.

Similarly, although in 1997 South Korea was on the brink of a domestic economic crisis due to the Asian financial crisis, they accepted the support and economic policies of the International Monetary Fund and overcame the danger. Afterwards, electronics manufacturers such as Samsung and LG, as well as Hyundai and other auto makers, prospered, and it is well-known that, in recent years Korean dramas and K-pop, as well as powerful entertainment such as Nanta and the martial-arts comedy show Jump have swept across the world and especially Asia.

In 2009, K-pop’s overseas sales of 32.5 billion won ($30 million), and have shown such rapid growth that 2010 sales were estimated to be double that amount. Korean artists are making inroads into foreign markets, focusing on Asia including Japan, and the production company SM Entertainment famously held concerts with some of them in Europe.

In other words, since the 1990s, Japan is the only country of these four that has been continuously unable to move forward, and the young people have been affected by these conditions in Japan.

Aging Population with a Low Birth Rate

The second possible reason is caused by the fact that young people form a lower proportion of the population. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the number of new adults (20-year olds) in 2011 was 1.24 million (630,000 men and 610,000 women), accounting for just 0.97% of the total population of 127.36 million; this is the first time since the Ministry's estimates began in 1968 that it has fallen below 1%. (The highest number of both population and percentage – 2.46 million and 2.40% respectively - was in 1970, when the first so-called baby-boomers, born in 1949, came of age). And the percentage of Japan’s total population over the age of 65 (the population aging rate) rose to 23.1%, setting a new record. The percentage of those under the age of 15 has fallen to 13.2%, confirming that the aging of the population is getting even worse. As a result, with over half the population over the age of 50, Japan has become something rare in the world, an elderly power.

Of course, South Korea is also an aging society, and China’s birthrate is declining due to the one-child policy. Nevertheless, a strong feature of Japan’s culture is that it is difficult for young people to launch startup businesses out into the world. In the bestseller Working for a Thousand Years: Japan, the great land of legacy businesses, it is written that Japan has over 100,000 companies that were founded more than 100 years ago, that there are almost no other cases of this situation in other Asian countries, and that Japan’s unique background is the reason. I think that there are good reasons for the survival of these companies, and that they have their attractions. However, in comparison with other Asian countries at least, certainly Japan’s national character is such that already-existing forces are strong and it is difficult for new ones to emerge.

Looking at the elections for governor of Tokyo in April of this year, basically the low turnout among young voters is a big problem with regard to their lack of participation in politics, but the candidate with the highest support of young people was different from the one actually elected. That is to say, as the youth population declines, so does its voice, and the number of young people who think, “Whatever we do, our opinions mean nothing” and who don’t go to vote increases. Doesn't losing their self-confidence flow naturally from the reality of being a minority with declining influence?

Evils of Relaxed Education

The third possible reason is the effects of relaxed education. In Japan, relaxed education means reconsidering the knowledge-oriented education that emphasizes memorization, and instead having a policy that aims for relaxed education oriented towards experience.

There is a strong correlation with the first reason, but to be precise I will point out that while they have been receiving this relaxed education, outside in the real world there has been that pervading sense of being unable to progress, so they could not enjoy this lack of pressure. There are fewer pages in the textbooks and both course contents and the number of lessons have been reduced. Furthermore, although since the 2002 school year, Saturday has been a school holiday and the whole school week is a five-day system, the best use was not made of the time left over for experience-oriented education. Naturally, academic results are on the decline.

The new company employees of 2010 have been generally referred to as the “first generation of relaxed education” and the decision to change this policy was made in 2008, but because it cannot be changed immediately, in high schools it will continue like this until 2013. They have grown up on the receiving end of bashing from every side as adults and the media say, “The relaxed generation is no good.” Even though relaxed education itself is a system created arbitrarily by adults, “We can’t study as well as previous generations,” “Previous generations often tell us we learned that pi is 3, not 3.14,” and “We grew up with our parents telling us that, because of this, the relaxed generation is useless” are actual responses from interviews with current high school students. Naturally, self-confidence doesn’t bloom when they are evaluated by society in this way.

Also, the new company employees of 2010 are affected by the financial crisis of 2008 and so on. They really are the “employment ice-age generation.” According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the employment rate for 2011 university graduates (as of April 1) is 91.1%, and since the survey started in 1996, this equals the previous lowest record set in the “employment ice age” of 2000.

Of course, it’s possible that when today’s high school students are job-hunting, there will be another boom in the business cycle. However, the trend towards unstable employment in the young age group is likely to continue for some time. Is the recent increase in the number of new hires saying they want to work until retirement age a sign of their lack of confidence?

“Galapagos Culture” of Young People

The fourth possible reason is the “mobile-phone culture” of young people. In fact, more than the whole society’s sense of being unable to progress, this feature is peculiar to Japan and I think it has an enormous effect.

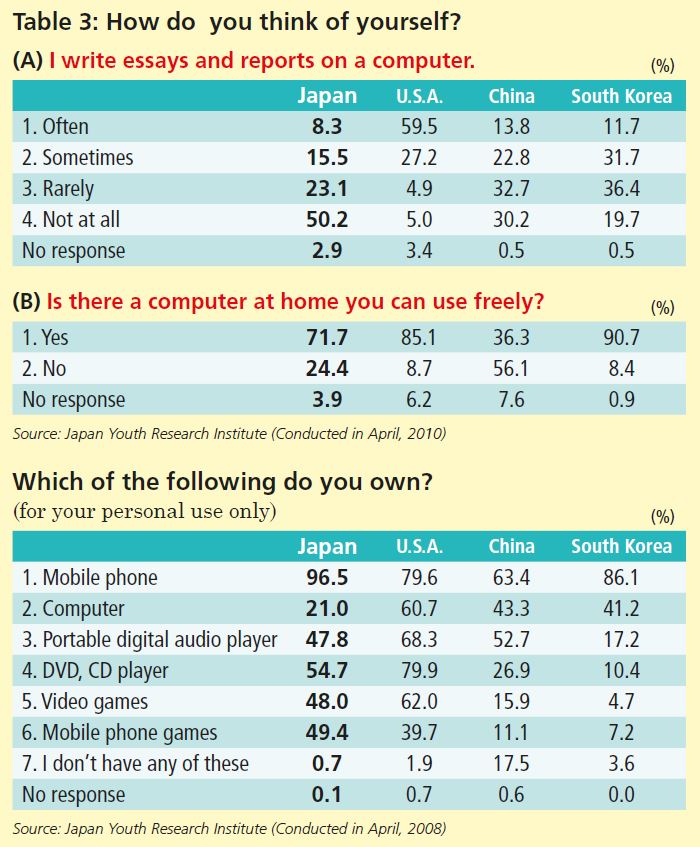

Once again, looking at the survey by the Japan Youth Research Institute published in April 2010, we learned that the percentage of high school students who use a computer when searching the Internet, studying or writing reports is by far the highest in the U.S., while the rate is extremely low in Japan.

That is to say, in contrast to the “computer culture” of the world’s young people, only Japanese youth have instead a “mobile-phone culture.”

At one time, Japan was the land of advanced mobile phones. With the ability to use a phone to take a photo and attach it to email (sha-mail), and dedicated websites to view on phones, symbolized by Docomo’s “i-mode,” Japan’s mobile phones led the world in the creation and spread of new features. The result is that, for as long as they can remember, Japanese high school students who own mobile phones think, “I can do anything on my phone.” With this situation, the “mobile-phone culture” (or rather, one could call it “mobile-phone dependence”) of Japan’s youth has developed, and it has kept them away from computers.

While Japanese young people have been sinking into “mobile-phone dependence,” the world’s youth (with more limited mobile-phone technology) have been using their phones for making calls, sending text messages, etc., and mainly using computers for everything else.

In fact, one result of the same survey showed that the percentage of high school students who have their own mobile phone is highest in Japan, but the percentage with their own computer is the lowest.

Although Japan’s young people share a computer at home with their family, many of them use it mostly for downloading music and watching their favorite singers’ videos on YouTube. Quite a lot of them cannot touch-type on the keyboard (even though there are people who can touch-type or type with both hands on a mobile phone!).

Many features are installed on Japanese mobile phones, such as music players, internet access, cameras, email, and games. And because these phones were too far ahead of the world, even without smartphones the young people were satisfied with these “Galapagos phones” produced in Japan.

Mobile-phone Culture (Galapagos-phone Culture) vs. Computer Culture or Smartphone Culture

As it turns out, “mobile-phone culture” (“Galapagos-phone culture”) is bad. And “computer culture” is good. The reason is that on a Galapagos phone, only dedicated mobile websites can be viewed, but on a smartphone, general sites can be viewed in the same way as on a computer. As mobile sites have been designed for viewing on small screens, the amount of information is small. And when compared with computer sites, the number of mobile sites is much lower. This means that, when you search for a keyword, many ordinary computer websites come up in the results, but there are also mobile sites which are filtered out and don’t appear at all.

In this way, with their experience of Galapagos phones that produce insufficient search results or even no result, young Japanese hardly bother to search for information at all.

When they talk about what they do on their phones, they mention email, social-networking sites, blogging and updating their profile (recently, this is on Twitter), so it seems that they are just constantly playing around with social media. That is, with the spread of the Galapagos phone, the mobile-phone-dependent youth of Japan have stopped looking up things they don’t know and are only engaging in idle gossip.

To get general information about current events, too, they open Mixi (Japan’s biggest SNS with about 20 million users) on their Galapagos phone and at most read some tabloid-fodder type Mixi News, or just the blogs of many friends. It’s no exaggeration to say that they have discarded general information and switched to only reading word-of-mouth news.

Putting Their Effort into Building a Village Society

This means that, with their Galapagos phones, they have given up on the useless activity of searching for information, and are putting most of their time and effort into their relationships with friends and acquaintances.

For example, if someone writes, “Lately, I feel depressed…” on their blog, even a lot of casual acquaintances must write comments such as, “Are you OK? You can talk to me.” In itself, this behavior is very kind. But it means that, if they have to spend all their time on this kind of thing among their large network of friends and acquaintances, they can’t make time for anything else.

For example, if someone posts, “So-and-so is annoying” on Twitter, they have to worry whether it’s about them. If it’s about someone else, even if they disagree, they must write something sympathizing with the poster. If they don’t come into line like this, next time it will probably be them who are called “annoying.”

I call these relationships within word-of-mouth networks of over-connected young people the “new village society.” Japanese youth have used their mobile phones to create many villages among themselves, full of gossiping and back-biting, where the stakes that stick up get hammered down.

They Know the Reality of Where They Stand

This means that this unusual “Galapagos-phone culture” is hastening the development of this “village society” culture among Japanese young people. As a result, because they are afraid of becoming the “stake that sticks out” and they take care to “read each other’s air,” they cannot assert themselves proudly and confidently. Isn’t this the culprit that has taken away the confidence of Japan’s youth?

Also, with “mobile-phone culture,” receiving the non-stop input of their friends’ word-of-mouth information, they have become very aware of their own relative position. To give a simple example, boys who haven’t had a girlfriend, learning through word of mouth that their friend has a girlfriend, become strongly aware that they themselves are not so popular. This is despite the fact that the majority of the boys do not have girlfriends. In the past, young people did not know so much about their friends’ private information, such as having a girlfriend, or test results and scores. They could be like the frog in the well, and it was easy to have unfounded confidence.

Of course, while it can also be said that today’s youth are precocious and mature, lacking unfounded confidence is not necessarily a bad thing. But, along with the unfounded confidence of youth, previous generations probably also had the ability to take action.

When interviewing today’s young people, the words “anyway” and “so/such a” often come from their mouths. “Anyway, I’m so unpopular.” “Anyway, what I think is not such a big deal.” “Anyway, the relaxed generation is so useless.” And so on. In other words, their loss of confidence has come from knowing the reality of where they stand.

And that’s where my study of the reasons Japan’s youth have lost their confidence was supposed to end. But in fact recently, I have felt that the potential of significant change coming to them has appeared.

This was the Great East Japan Earthquake which happened on March 11, 2011 and this ongoing corona virus pandemic. Having experienced such big events during their youth, it is possible that, like the wartime generation, they will begin to develop determination and toughness. Many young people have been holding fund-raising campaigns in the streets, and a lot of them have also gone to volunteer in the stricken areas. The increase in couples getting married since the disaster has been reported quite often in the media, and this is probably also an example of young people’s determination.

Young people, accepting that the world is unstable to begin with, rather than feeling threatened by that instability, may contradict the argument that they have become stability-oriented. For example, young entrepreneurs may appear. The number of young people who, think it’s a shame not to enjoy life without fearing the over-connected relationships of mobile-phone culture, who become “AKY” (an acronym for the expression meaning “dare to be unable to read the air” – Aete Kuki wo Yomenai wo enjiru) and stop “reading the air,” who concentrate on doing what they love, will probably increase.

Whatever happens, personally I have high expectations of seeing Japanese young people, who had lost their confidence due to many intricately intertwined factors, making some big changes in the wake of the earthquake.