Behind Japan's Sad Young People

CONTENTS

BEHIND JAPAN’S SAD YOUNG PEOPLE

You were born just after the bubble economy which ended in 1992. You started work and then the Lehman Shock happened. You live in the era of the carnivorous woman. Maybe you’re just getting used to that world and then the Great East Japan Earthquake creates a whole new round of depression.

It does not sound like a great life, but for many men in their 20s, that has been and is the story of their lives.

The Work Life of Japanese Young People: The Ideal and the Real

Think of a Kenji, a typical 21 year old. For his whole life, his father has talked of the bubble years in the 80’s, of the fast rising incomes and lifestyles, and of careers that were incredibly secure and stable and while involving much hard work and sacrifice were also very productive in seeing their companies and personal wealth grow. But Kenji has known none of that. On finishing university in 2011, he would have seen fast decreasing opportunities for new grads. An increasing number of his peers either have missed out on permanent jobs or if they found one, they discovered that the corporate world is changing and that the future is less secure.

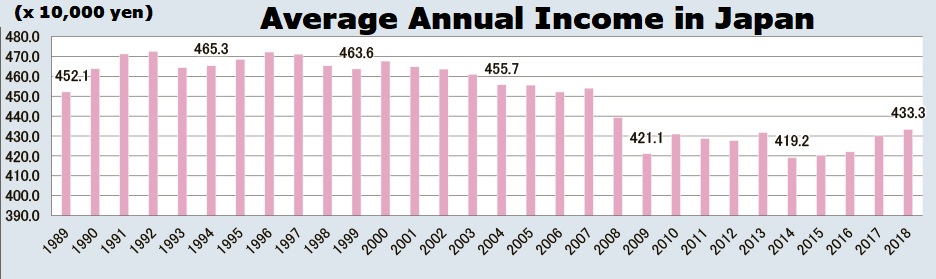

(The above table may appear to be improving recently, but this is because the average age of the working population is rising, and the real wages of young people have remained the same or even declined.)

Even if he did find a permanent job, the post Lehman reality means his work life has changed. After work bonding sessions are much less frequent as everyone cuts down on entertainment expenses. Salaries are not rising and so he is not able to start saving. And importantly overtime payments are also down. We have tracked recent economic downturns and found that whenever there is one, there is a corresponding rise in late night television viewing by young men. Some marketers see this as a great opportunity, the “return of audiences to TV.” But of course it is actually more fuel for loneliness. Not enough overtime work means less money to go out or to buy entertainment with, and more time at home doing what is free like watching television - often alone.

Of course this is also the age group most active in using on-line information and social media. Kenji has grown up in the first generation that fully lived a “virtual life” immersed in role play games on their PCs and their mobile phones. And yes, while they are big users of social media, though not as big as their female peers. However there is a lot of discussion now that social media in some ways keeps us more in touch with a wider group of people but leaves us with less deeper relationships. For Kenji, that has often meant just less time in real life bonding with others.

And let’s not forget that Kenji has been flooded with “too realistic” news about the double punch of the economy and then the post earthquake situation that continuously rocks his belief in his ability to cope. A tough environment with a very doubtful economic future, less money to enjoy life and hearing bad news leads them to shutting themselves off in virtual worlds. So maybe it is not surprising that Kenji is feeling a little sad, and a lot lonely.

Satisfaction with Life Rates Lower

For the last eight years, we have run regular surveys into the way people in Japan of all ages think about their lives and the future of the country. In one exercise, we ask respondents to rate their satisfaction with their current lives on a scale of 1-100. Sadly and consistently the national average never seems much higher than 60, a reflection of both overall dissatisfaction and also a Japanese tendency to downplay their situation. Unfortunately single men in their 20s and early 30s always give their lives a score among the lowest across the population. We also ask that people rate their expected lives in the future and usually find that the average is an 8-10 point rise within five years and a further 5 points within 10 years. Usually young men like Kenji are the most hopeful and likely to expect life improvements. However since the earthquake of 3.11 we have asked the same questions in each of the three rounds of our “FUKKATSU (recovery): Japan Rebuilds” research into how Japanese people are coping with recovery. The results of those three rounds of research clearly indicate that young men are now the most pessimistic segment of the population.

Two weeks after 3.11, we found that young men’s rating of their own lives had sunk to 44 when the national average was 56 making them the most depressed age group. And 10 weeks after 3.11, their self rating was only 37 out of a 100 while the total country average had actually risen to 59.

In addition, the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has increased the suicide rate among young people. It is not hard to imagine that hope for the future is even lower.

What is really surprising is the difference between men like Kenji and women their age. Again women in their 20s-early 30s had lower satisfaction and expectations than the general population, but it was much closer to the average. Ten weeks after the earthquake, their life rating was 52 (compared to a national average of 59 and the dismal 37 rating by Kenji and other young men) and an expected life rating in 10 years time was 77, the highest of any age group, well above the overall average of 70.

The Earthquake Has Changed the Way of Real Life

We have also been tracking the words that people of all ages use to describe their current lives. Not surprisingly since 3.11 the most common word that people of all ages use to describe their lives is a desire for “stability.” They also use “anxiety” a lot. But surprisingly there is continuing use of words we had seen before the earthquake “fulfillment,” “happy” and “freedom.” These are all used in connection with a desire to make the most of life. In fact over the last five years, we have seen increasing use of the word “freedom” in regards to how people from teens to retirees describe their own lives. A key reason being that in small ways they can see their lives as more free than the past. Up until quite recently, we found 20-30 year old men using the same language.

Since the earthquake, young men still talking of stability and indeed many still talk of “hope” and “growth” as key words to describe their lives and what they want from the future. But “anxiety” has become more important and for the first time in eight years of the study we have seen the use of the word “loneliness.” Why? Certainly the earthquake has triggered some of this. In a similar vein our tracking of 20-30 something women has found that for the first time in eight years of tracking “marriage” is among the top four words they use for how they feel about their lives. So young men are feeling lonely and young women are more inclined to be thinking about marriage. Maybe they are both natural reactions to living through a dramatic, life threatening event. And, yes you could argue that getting the increasingly lonely young men together with the women who want to get married might solve everyone’s issue.

However, this “loneliness” seems more than not having a wife.

The real truth lies more in Kenji’s personal history of growing up in tougher times, of not seeing the bright future his parents had told him about and a lifetime of easy distraction in virtual worlds that has left him wondering how he connects more with people and a fulfilling life in the future.