Shared House Rentals Take Off in Japan

CONTENTS

By John Mori

House sharing has become Japan’s newest popular trend, especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

The capital city has seen a particularly rapid rise in shared-rental opportunities targeted at younger people. These homes offer each tenant an individual bedroom along with a shared kitchen and living room. Among the reasons cited for their growing popularity are: “affordability,” because of the absence of either refundable or non-refundable deposits (the norm for rentals in Japan); “convenience,” because shared rentals are usually complete with basic furniture and appliances, including a TV and refrigerator; and a “sense of community” among the tenants.

Residents of these homes say that having roommates with whom they can talk during meals gives them a more fulfilling lifestyle and eliminates the sense of insecurity that often arises when living alone. Some rental properties pursue very specific renters: for example, “women who moved from rural areas” (to help each other overcome the stresses of adjusting to an urban lifestyle); “single mothers and elderly individuals who want to help one another”; or even “professionals in the IT industry.” Generally, shared homes describe themselves as places in which renters can “interact with” and “support” each other.

While the vast majority of shared rental units are intended for single people, one of the newest additions to Tama City (in the western suburbs of Tokyo) is a condominium in which 20 families share living areas and kitchens. The goal of the building is to restore the historic Japanese sense of community within a modern lifestyle by living together cross-generationally. In today’s “indifferent society,” where neighbors do not know each other and even relatives no longer communicate (see our feature story titled “Japan’s Changing Funerals” in the February 2011 issue), the popularity of shared rentals is a clear indication that many people want to revive at least some aspects of “the good old days.”

Just a five-minute walk from Kyodo Station in Tokyo, five women and two men – all Japanese nationals – live together in a house in one of Setagaya City’s quiet residential districts. The residents are all around 30 years old and have varied professions. Akiko Nakata, for example, is a 31-year-old clothing designer from Ibaraki Prefecture who enjoys the living arrangement in the shared house. “My bedroom comes with a solarium,” she notes, “and the furnishings throughout the house are pleasant as well.” Ms. Nakata had previously lived with a boyfriend and with her brothers and other friends, but had never before lived with people whom she didn’t already know. At first she was naturally concerned about her new housemates, but she is now satisfied with a home in which she gets to “meet people I wouldn’t have met otherwise, such as professionals in different fields.” Rents in the house range from 54,000 yen ($675) to 76,000 yen ($950) per month, depending on the size of the bedroom. There is also a common charge of about 10,000 yen ($125) per month per tenant to cover utilities, including Internet access. Just opened this past April, the shared home has provided a pleasant experience so far, although Ms. Nakata mentions such minor annoyances as “other residents not putting back used cups and pans, leaving without locking the door, or not replacing the toilet roll.” Nevertheless, she says, asking her fellow tenants to be more considerate does not seem to hurt her relationship with them.

Masataka Ishikura, a 25-year-old systems engineer from Ehime Prefecture, lives in a house near Meidai-mae Station, another residential area in Setagaya City. He previously lived on his own, but the tenants of his apartment building got along well and frequently had parties together. He therefore decided to look for a shared rental when it was time to move. “I like to be surrounded by people,” says Mr. Ishikura, who now lives with five other residents who share a living room, kitchen and bathroom. Mr. Ishikura is more than satisfied, not only because he reduced his monthly rent from 72,000 yen ($900) without utilities to 70,000 yen (875) including utilities, but also because he now has a larger living space in which to relax.

Mr. Ishikura says he is a neat person, which is evident in his organized bedroom.

Akiko Ando of Korento Ltd., which manages about 20 shared rentals for women in and around Tokyo, explains that “offering less expensive options in terms of the initial deposits and rents” is part of the appeal to potential tenants. “But the real differentiation is how much value you can add, such as larger common areas and pleasant interactions with roommates.” Korento’s shared rentals do not require the typical deposits – normally a refundable two-month rent plus a non-refundable two-month rent (“gratuity for the landlord”), but do charge an initial fee equivalent to one month’s rent. When the tenant moves out, the fee is usually refunded, minus a cleaning fee. Tenants also save by not having to purchase such basics as furniture, a TV, washer, drier and refrigerator, which do not come with traditional rentals.

“Most people here seem to have chosen this living style because they wanted to have more fun, or they wanted to have friends to go out with on weekends,” says Mr. Ishikura, who has lived in his shared rental for almost two years. Ms. Nakata thinks it as “a part of life’s experience.” Akane Kubota, who manages Ms. Nakata’s shared house near Kyodo Station, notes that “many people think this is one of the things they want to try at least once.”

Although the economic and social aspects of house sharing are important attractions, residents also point to another more recent factor: the 3.11 earthquake. Since the earthquake and tsunami that devastated Northeastern Japan on March 11, 2011, many women came to feel unsafe and insecure living alone, says Ms. Nakata. Wakako Ito, a housemate of Ms. Nakata’s, agrees, adding “I feel safer having someone in the living room. We actually talk about this reassuring feeling after the quake.” Ms. Ando of Korento attests that the level of interest in shared rentals has risen since March 11 because some people were left without roommates in Tokyo after friends moved back to their hometowns, while others wanted to move closer to their workplaces.

Shared homes under Ms. Ando’s management also appeal to somewhat overprotective parents who have just sent their children into the world. “Those parents might say they are concerned about their daughter living alone in such a dangerous world, or they might want their daughter to gain basic living skills through communal living,” she says. “Some parents are embarrassed that their daughter doesn’t even know how to wash dishes.” Indeed, some of her tenants refer to leaving the shared rental as “graduating.” While the reasons for leaving vary from study opportunities abroad, moving into a single apartment or getting married, Ms. Ando thinks the term “graduation” suggests that shared living is proving to be a genuine learning experience for many young renters.

Kazufumi Endo, a 40-something professional who used to work for Microsoft Japan, chose to live in a guest house during 2006 not for financial reasons, but because he could meet a wider range of people. The guest house, located in the middle of a business district just a 10-minute walk from Kanda Station, is still home to more than 20 Japanese and foreign residents. Mr. Endo’s room was about the size of four and a half tatami mats (about six and a half square meters). While he admits that he couldn’t help stepping on the futon that was permanently spread on the floor as soon as he opened the door, Mr. Endo couldn’t resist a location from which he could walk to his office in minutes. More than 20 rooms in the guest house come in various sizes and rents. The shared living room and kitchen is about 30 tatami mats, or about 43 square meters. Mr. Endo used to enjoy parties and other events that took place several times a month in the shared space. “I met many interesting people there,” he recalls. “The tenants also invited their friends, which turned out to be a fun networking opportunity.” Although Mr. Endo used to pay only 50,000 yen ($625) per month, including utilities, it became apparent to him that the guest house was not a place where he could live permanently. He now rents an apartment near Tokyo Station for about 100,000 yen ($1,250) per month.

Tomoko Makino, a 20-something who works for a design firm, describes her experience at a shared rental as a necessary choice due to her financial situation. “I lived in a shared rental for about a year and half [beginning in 2007], but I would never do it again,” she says now. Her place accommodated about 15 tenants, mostly Japanese nationals from their early 20s to their 50s. “There was a party every night and I couldn’t sleep because of the noise,” she remembers. “There was also a tenant whose room was so dirty that it smelled when I passed by. Some people regularly used belongings of other tenants without asking. Someone even ate a dinner I had cooked and stored for myself.” The only upside was the rent, which was just 35,000 yen ($437) per month, including utilities. At that level, a place like Ms. Makino’s would certainly appeal to young people with limited financial means.

The Reality of Sharing: How the System Works

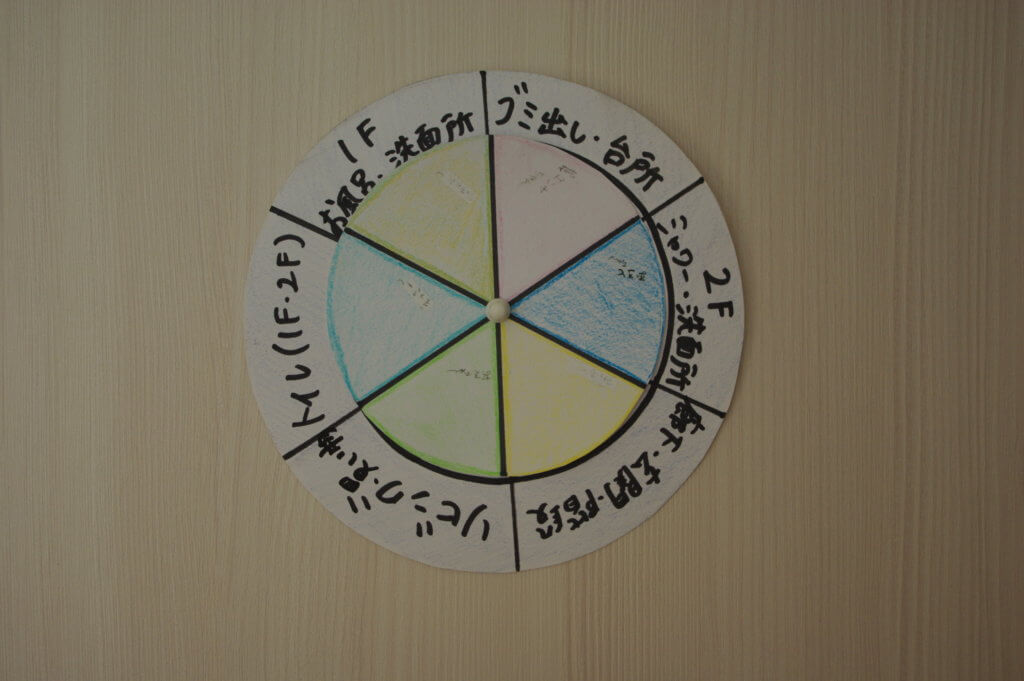

Living alone is carefree, with no one nagging you about a messy room. Sharing a living space with someone else, however, is an entirely different experience. You must be considerate of your housemates by cleaning and putting away dishes or making sure windows and doors are locked. Responsibilities have to be governed by basic rules, such as how the space in the refrigerator or pantry cabinets should be shared, who should clean the common rooms or who should replace kitchen detergent or toilet paper rolls.

“In-house administration is up to the tenants,” says Ms. Kubota, who manages the shared house in Kyodo. “I haven’t had any major issues because all of my tenants are good.” Supplies for cleaning the common spaces are purchased with the monthly stipend provided by Ms. Kubota, but cleaning schedules and assignments are set by the residents themselves. Mr. Ishikura’s shared house is also run autonomously, although the only common cleaning duty is the bathroom, which is a weekly chore taken in rotation.

Each basket has a color sticker to identify each renter.

Each item in the fridge has its renter's initial name.

If you put your color of the sticker, you are willing to set things in order.

Some of the larger homes with more residents tend to hire a cleaning company for common areas. The guest house in Kanda where Mr. Endo lived, for example, had a cleaning company visit on a weekly basis. Mr. Ishikura supposes that shared homes with 20 to 30 residents inevitably become dirty in a much shorter period, while homes with fewer than 10 people are manageable autonomously. Ms. Kubota agrees that it is better not to involve a management company in order to encourage communication among the residents.

Korento takes the same stance. “It is our deliberate decision to let the tenants run the place to foster their communication skills,” says Ms. Ando. The management company may suggest examples of effective strategies, but it does not present them as “rules.” This approach has resulted in some efficient and effective new ideas, according to Ms. Ando.

They rotate a house chore among each other.

A message notebook for other renters

On the other hand, some high-end shared rental properties in prime locations in Tokyo boast complete services, including cleaning of individual bedrooms. These hotel-like rentals are not inexpensive, ranging from 100,000 ($1,250) to 160,000 yen ($2,000) per month for a location in the heart of trendy Omote Sando, for example.

Appeal to Foreigners

Shared houses are popular with foreigners as well as among Japanese. Adam Hacker, who moved to Japan last December, has lived in “foreigners only” shared housing near Shibuya, downtown Tokyo, ever since. Location is the biggest draw for Mr. Hacker, who is in his 20s. “I go to work by bicycle,” he says. “And I can walk home after a late-night outing without relying on the train.” He also liked the fact that a conventional deposit – normally equal to four months’ rent in total, half of which is non-refundable – was not required. “I wouldn’t have been able to come to Japan if I needed 300,000 yen ($3,750) just to start living here,” he notes. His living environment is an individual bedroom about the size of six tatami mats (about nine square meters) and a shared living room and kitchen. The common areas are cleaned by the management company once a week. He pays 90,000 yen ($1,125) per month, which includes the management and utility charges. “My friends tell me that I can find a cheaper place, but I don’t think this is so expensive,” he says. Mr. Hacker plans to stay for some time, although ideally he would prefer a place he can share with Japanese people, too.

While foreigners usually choose a shared rental property administered by a management company, more experienced individuals sometimes prefer to lease a house on their own and share it with friends. Pavel Prosselkov, a Russian in his 20s who works for Riken, a research institute overseen by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, rents a house with a yard in Wako City, Saitama Prefecture, adjacent to Tokyo. The total cost is 120,000 yen ($1,500) per month, but, says Mr. Prosselkov, it is only 40,000 yen ($500) per person when you have three residents sharing. “I love traditional Japanese houses,” he says. “I always wanted to live in one with a yard.” He is currently looking for housemates among his circle of friends, adding that it is especially enjoyable to live with people from different countries – including Japan.

Home owners used to be reluctant to rent their properties to foreigners, and visitors to Japan often had a hard time finding suitable accommodation. The situation is changing, however. Mark Dominey, an American missionary who has visited Japan many times in the past, testifies to his experience. “When I first visited Japan 15 years ago, I called on a number of brokers but couldn’t find a single home owner who was willing to rent to me,” he remembers. “It has become much easier these days.” He and his family now rent a three-bedroom apartment in the suburbs of Tokyo.

Shared rentals originally developed in Japan as a choice for foreigners who had a hard time finding their own rental, according to Daisuke Kitagawa, owner of Hituji Incubation Square, Inc., which since 2005 has maintained a real estate website specializing in shared homes. “Shared housing began popping up in the early 1980s as a niche for foreigners who wanted to live in Tokyo but were shunned by owners,” says Mr. Kitagawa.

Early shared homes were relatively expensive, but they easily found tenants. Prsmac Husanov, a former researcher at Riken who comes from Poland, used to pay 100,000 yen ($1,250) a month for a room in an old three-bedroom house that was a 15-minute walk from the centrally located Takada No Baba Station in Tokyo. When he first looked at the 40-year-old house, he noticed his room was only about the size of six tatami mats and its floor was so slanted that it cried out for repair. Nevertheless, he took it. The Takada No Baba area is known as a college town with plenty of apartments offered at reasonable prices, and in actuality there are postings in the windows of real estate offices advertising more spacious apartments in younger buildings closer to the station at 100,000 yen or less, with dedicated bath and lavatory rooms.

Another growth factor for shared homes was the increasing conversion of company housing into apartment buildings. Until the 1990s it was common practice in Japan for mid- to large-sized companies to offer economical living options as part of employee benefits, especially for entry-level workers. However, such company dorms or apartments lost popularity among younger generations, who regarded living close with colleagues as a nuisance. The pressure for cost-cutting also pushed employers to sell their dorms. Many of these housing facilities were reborn as apartment buildings so-called “One Room Mansion” or shared rentals for foreigners. The trend was accelerated after 1991, when the Japanese bubble economy collapsed. For example, converted in 1993, an apartment building in Saitama City that houses 45 one-room units is one such former company dorm.

Diversification After Gaining Popularity Among Japanese

Under new ownership, many buildings began catering to foreigners, and later started accepting Japanese residents as well. Initially serving foreigners living in Japan, shared rentals started seeing more Japanese residents who were interested in the lifestyle, networking opportunities or financial benefits beginning around the year 2000. Mr. Kitagawa of Hituji Incubation Square is a former programmer, and he once lived in a shared rental “because it looked like fun.” He estimates that 30% of people who chose to live in a shared rental were primarily interested in the seemingly fun lifestyle; another 30% were looking for networking opportunities with foreigners; yet another 30% came for financial reasons; and 10% considered it an opportunity to brush up their language skills, especially in English.

Now, as they move closer to the mainstream, shared rentals are becoming more sophisticated and sport a variety of styles. Just a quick look at some of the postings on Hituji Incubation Square’s website reveals numerous listings with such diverse descriptions as “girls’ special,” “spacious,” “cutting-edge” and “artsy.” Most of the site’s more than 10,000 listings are chic and stylish because the owners of these rental properties make sizable investments in them. “Shared rentals and elderly homes,” says Mr. Kitagawa, “are the only two bright spots in the depressed housing market.”

A prime attraction of shared rentals for house owners is the high occupancy rates they produce. While a three-bedroom house may command 120,000 yen ($1,500), it is harder to find a tenant – a single person or a family – who could afford such a rate. It is easier to find three tenants who are each willing to pay 60,000 yen, which results in a total income of 180,000 yen ($2,250). Just two tenants and one vacant room would still bring in 120,000 yen. Even with added maintenance costs, the initial investment to convert a property to a shared rental can be attractive. Ms. Kubota, who manages the house near Kyodo Station, realized that turning her parents’ two-family house into a shared rental would make sense. “The number of family members varies from time to time. But the size of a house never changes,” she says. “You couldn’t avoid inefficiency especially with a two-family home.” After considering many options, she decided to convert the house into a shared rental. Thanks to the differentiating factor of artistic interior decoration, she filled up her place in no time. As Mr. Kitagawa of Hituji Incubation Square notes, “If you have a good property, you have no problem finding tenants.”

Shared rentals are divided into two types: those that are renovated for the purpose and managed by a company, such as many properties listed on Hituji’s website; and those that are essentially a regular house that is shared by friends or acquaintances, as in the case of Mr. Prosselkov. Although there is no official count, Mr. Kitagawa assumes that fewer than 1,000 houses of the latter type exist in all of Japan. “House sharing is not all fun and trendy,” he says. “Issues are inevitable.”

Problems that include recycling, cleaning and noise are abundant, and they can easily cause housemates to fall out. With a management company to intervene, however, most issues can be arbitrated and resolved before developing into major disputes. Many management companies also interview potential tenants to see if they are good candidates for communal living. “Cooperativeness is the minimum requirement,” says Mr. Kitagawa. “But they also try to determine if the candidate can get along with the existing tenants.” Ms. Kubota agrees with that approach, adding that she “carefully selected good people for my place.” Rather than conducting official interviews, Ms. Ando of Korento uses the property showing as an opportunity to see if the potential tenant is a good fit. “I can tell [if candidates have a suitable character for shared living] from their manners and behavior during the showing,” she says. These selection processes have been effective in preventing troubles.

Hituji Incubation Square only deals with shared rentals managed by companies. Currently they count some 11,000 listings. “You may read and hear stories through various media about people sharing ordinary houses,” says Mr. Kitagawa, noting that the upcoming film “Share House,” set for release in November, is expected to be about people sharing a regular house without professional management. “But in reality, the vast majority of shared rentals are administered by a management company.”

Either way, the core benefits of shared living are essentially the same. “It is one remedy and a good trend for a modern society in which people are indifferent to others and where the sense of community is diminishing,” says Shinji Miyadai, a professor of sociology at Tokyo Metropolitan University. According to Mr. Kitagawa, “contact” is the first and foremost attraction of shared living. The longing for contact can be a response to urbanization, which has produced more people living alone and more people feeling lonely. Ms. Ando thinks that the pendulum is swinging back to an emphasis on community after the bubble economy that drove individualism.

For now, most shared rentals in Japan are concentrated in the Tokyo metropolitan area, but it might be just a matter of time before the trend spreads to other regions. More Japanese than foreigners now live in a shared-living environment, although “an increasing number of shared rentals are high grade, which can appeal to foreigners who want to meet and make friends with local people,” says Mr. Kitagawa. “I want foreigners to live and mingle with Japanese people,” he adds. “I believe this international exchange will help to solidify the foundation of Japanese society for the future.”

John Mori is a Japan-based freelance journalist and photographer with an interest in social trends.

Read a related article: Accommodating Muslims in Tokyo, Japan

2 thoughts on “Shared House Rentals Take Off in Japan”