Origin of Japan’s Business Philosophy: Righteous Merchants of Ohmi

CONTENTS

The Omi merchants were merchants from Omi Province (present-day Shiga Prefecture) who were active from the Middle Ages to the modern era. They are one of the three major merchants in Japan along with the Osaka merchants and the Ise merchants. Even today, entrepreneurs from Shiga Prefecture are often referred to as Omi merchants. Normally, the term "Omi merchant" is used to refer to merchants who expanded their business outside of Omi.

Below is some of the major corporations whose founder was from Ohmi province.

- Seibu Railway, Seibu Group, Saison Card (Founded by Kojiro Tsutsumi)

- Takashimaya department store (Founded by Shinshichi Iida)

- ITOCHU Corporation and Marubeni Corporation (founded by Chubei Itoh)

- Sumitomo Zaibatsu (The first general director, Saihei Hirose)

- Sojitz (both Nissho Iwai and Nichimen, the parent companies, are descended from Ohmi merchants)

- Tomen (founded by Kazuzo Kodama from Hikone, merged into Toyota Tsusho in 2006 and ceased to exist)

- Yanmar (founded by Magokichi Yamaoka from Ika-gun)

- Nisshinbo

- Toyobo

- Toray Industries, Inc.

- Wacoal (Founded by Koichi Tsukamoto)

- Nishikawa (Founded by Niemon Nishikawa, a native of Yawata)

- Toyota Motor Corporation (The first president was Risaburo Toyoda from Hikone of Ohmi province)

- Nippon Life Insurance (founded by Sukesaburo Hirose, a Hikone native)

- Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited (a goodwill company from Ohmi-ya Kisuke, a pharmaceutical intermediary that originated in Hino)

- Nichirei (Teikoku Suisan, its predecessor, was founded by Teijiro Nishikawa and others from Yasu County)

Over 700 years ago, the merchants of a small town in west Japan developed unique and sensible models for ethical business practices that live on even today!

Selfish Behavior Is to Be Avoided (precept)

“Once people become wealthy, they become arrogant. Once they become arrogant, they become impolite. Once they become impolite, they become hated. Once they are hated, their misfortunes follow one after the next. Once they suffer misfortunes, they incur losses. Once they lose, they fall into poverty. Once they fall into poverty, they commit crimes. Once they commit crimes, their lives are ruined.”

In these words, from a set of family precepts among merchants from the domain of Ohmi, which is now part of Japan’s Shiga Prefecture, warned that “people ruin themselves if wealth were to lead to arrogance.”

Now look at the situation today, with frequent corporate scandals; widespread evidence of lack of business ethics due to greed; and Japan’s economic downturn. Is Japan on a steady decline? If so, why? Perhaps it may be resulting from people’s having forgotten the “basics and significance of business” and “involvement with people and the community and social responsibility.” In short, they are guided not by “doing business for the benefit of society,” but see their essential purpose of business as “making money.”

Making money is not wrong, rather necessary for our society. The essential way is to do it right, so as not to cause the system to break down, which is what occurred with the “Lehman Shock” in the United States and the financial crisis in Greece.

For many issues, from the earth’s environmental problems to the pros and cons of nuclear power, the clues to solutions can be found in the philosophy and way of life of the “Ohmi merchants,” who, it has been said created one of the foundation of modern commerce in Japan.

Fortunately, business philosophies and living style of Ohmi merchants still live on, much as it did at the time of their founding hundreds of years ago. Some of their more famous descendants include the Takashimaya Department Store, Wacoal (maker of female undergarments and clothes), Yanmar (manufacturer of farm equipment), Nisshinbo (spinning and textile products and others), Nippon Life Insurance Company, Nishikawa Sangyo (bedding supply company), Marubeni Corporation (general trading company), Itochu Corporation (general trading company) and so on.

Products and manufacturing technology of Japan have achieved a favorable reputation in the world, with the result that Japan succeeded in catching up with and overtake manufacturing companies in Western countries. There are several reasons for their success. They had a strong dedication to keep advancing step by step. As known the Japanese word shokunin, craftsman in Japan, it is this unflagging spirit of diligence and dedication toward progress that has set an example for others. The Ohmi merchants’ business philosophy and life may have served as the guiding spirit for such pioneering company founders as Panasonic’s Konosuke Matsushita, Sony’s Akio Morita and Honda Motor’s Soichiro Honda. While the origins of the Ohmi system are not precisely known, it remains the ideal that Ohmi merchants follow even to this day. The philosophy is hinted from the words, “Merchants are to deliver fortune to the people.” The essence of business is hidden within those words.

Roots of Ohmi Merchants

What originally occurred in the town on the east coast of Lake Biwa, and why the Ohmi merchants started doing business there, is not entirely clear. However, they stayed at the town and continued to do business, even though they were active in other parts of Japan and achieved wider success during the Edo period (1603-1868). Moreover, the merchants made significant financial and cultural contributions to public works and projects in the town, as well as donating generously to temples and shrines.

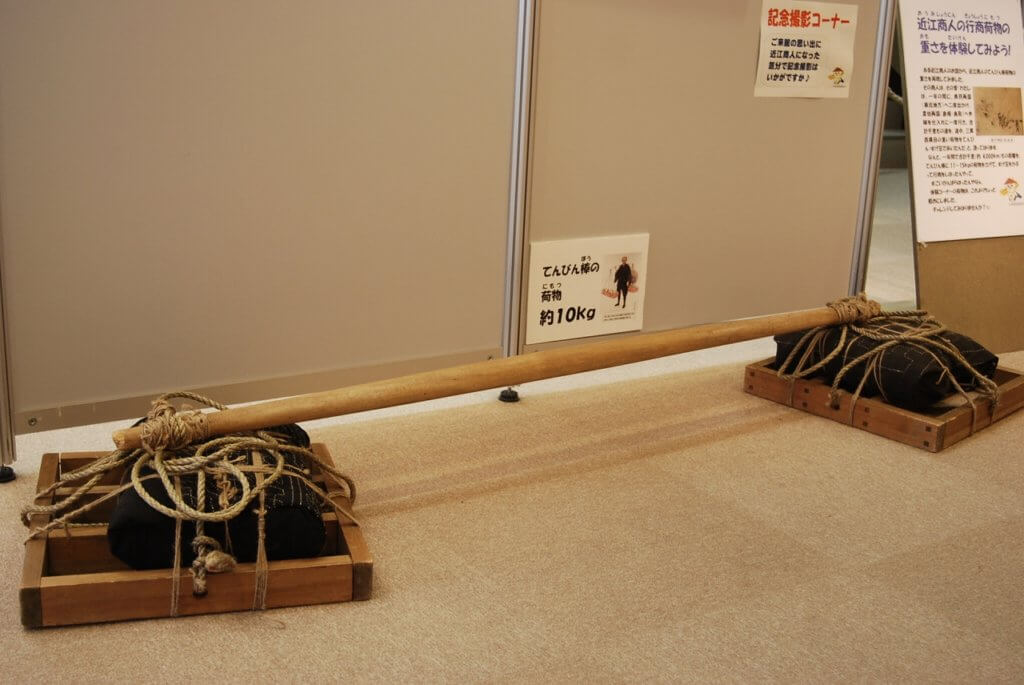

Ohmi merchants went on sales trips all over Japan often far from home. They dealt mainly in textile products that were produced around their home town, such as dry goods, cotton and hemp fabric, which they transported suspended on shoulder poles. Their behavior and the way of thinking as merchants remained consistent with their principles, bringing them success and affluence, which enabled them to establish branch offices in the main cities of Osaka, Kyoto and Edo, later Tokyo.

One of their most important principles was to think in terms of long-term business, with an emphasis on how the business would continue perpetually. They always kept in mind the concept of “Sow loss and reap gain.” But the most famous expression created by the Ohmi merchants, which brought one into touch with the roots of their management philosophy, was “Good seller, good buyer, good society” epitomizing the so-called “Sampo-yoshi,” that provided benefits to a company, its customers and to society at large, that is, among all three parties concerned. ITOCHU Corporation, for example, mentions this term on its web site. “Our history has been built together with the philosophy of sampo-yoshi. We intend to practice CSR . . . rooted in this principle going forward as well.”

Think business in a long term

Ohmi merchants dealt in goods far from their homes, to people who they met for the first time and with whom they were not well acquainted, to develop customers and expand their business. So they not only had to sell their goods, but also sell the intangible product of “trust,” which they believed was is the most important attribute. They must have trusted themselves and what they sold in order to lay a foundation for building firm relationship.

This sampo-yoshi philosophy is eloquently expressed in a letter written by Jihei-Sogan Nakamura, known as the “linen king,” to his 15-year-old son: “Keep in your mind: You should have confidence in the products you bring to customers, satisfy them and desire that the deal can be useful for people. Do business for people without considering gain or loss, which would meet with a good result and be up to how much you think of customers. Think of the benefits of customers first with esteem without desiring your own gain. Also it is very important to devote yourself to the gods.”

Ohmi merchants obtained trust based on sound management principles, and built a strong and good relationship between themselves and local customers throughout Japan. Such thoughts were also accepted overseas and the merchants expanded their business to customers in Vietnam and Thailand.

Precepts of the Merchant Family

Principles of Ohmi merchant played an important role as the commercial code and code of conduct as well as for business ethics. The merchants wrote down as many precepts as possible, so that future generations could also make use of the wisdom accumulated through their experience. The merchant family precepts have been preserved since the 18th century, and they also make references to samurai, members of the ruling warrior class, for the purpose of expansion and continuance of family business.

Many of the family precepts consist of observance of public affairs such as the practice of frugal living and working conditions of employment that included rewards and punishment.

Precepts were usually written down as a record of their valuable experience by successful owners for the employees and future generations. Precepts also advise that respect for Japan’s main religions, Shintoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, become the root of moral society.

Samples of Family Precepts

●Sampo-yoshi

Satisfaction among the three parties concerned. The concept of “benefit to company, customer and society.”

●Calculation and Aptitude of Business

What merchants need are not tricks or shrewdness, but proper adjustment of the supply and demand. Do not buy and sell, or hoard goods on speculation, and avoid unfair competition. Do not use political influences to forge deals.

●CSR and Social Contribution

Make contributions to society, such as by donations to shrines and temples, or school and bridge construction. To show thanks to society, use the money obtained through trading to help social services.

●Trade at Low-margin, High-turnover

Seek long-term trade arrangements rather than short-term that affords one-time large profits. Increase profits through always examining the best way to do business from various angles. Work hard every day from early morning to late evening. As they left home before sunrise and returned home late, they were able to see stars twice in a day. This custom is the reason why many of Ohmi’s merchants use stars in their stores’ logo marks.

●Be Thankful to One’s Ancestors

The prosperity of today was achieved because one’s predecessors worked hard. One should therefore work harder to protect the family business and maintain prosperity.

●Be Honest, Hardworking

Being aware that you are a member of the society, work hard and have consideration for others without causing trouble or dishonor.

●Be Cooperative

Cooperativeness is required when doing business in society. Hikoshiro Fujii (1876-1956) drew up a list of 15 things not to do --- which he called “People Who Interfere with Business”: Those who do not listen to others and cannot bear to hear advice of older people; those who do not have mind of appreciation to others if received favors and kindness; those who put off things to be done today till tomorrow; those who do not distinguish right and wrong or the importance of things, and so on.

●Be Agile

Do it right now in a timely manner.

●Have Foresight

Do not be misled by the short-term views by society. Act in anticipation of future. That is the basic knowledge about business.

The Life of an Ohmi Merchant

A newly hired apprentice starts work from around age 12 as decchi, an apprentice, who does chores for the family of a merchant under the system of personnel training and development. Next he steps up to tedai, a sales clerk mainly in charge of the sales section; and then to banto, a buyer mainly responsible to the purchase section. The next stage is shihainin, the supervisor of an entire department, and to gogen-shihainin, a manager responsible for the entire house. This was the typical promotion system of olden times, and it remains close to the one in current use at companies. Employees had the opportunity to become executives if they displayed a talent for doing business.

Leave System

After five years of work, apprentices were allowed to return to their family home for the first time. Home leave was great fun for the apprentice, because most of them worked far away from their parents. The leave could be taken again in the next two years. However, this time also gave merchants the opportunity to evaluate the apprentice and decide if they were to continue to be employed or be dismissed.

Salary

Daily supplies and garments, such as kimono (clothes) and obi (sash) were provided to apprentices, who also received a small monetary allowance. However, salary was determined by length of service, and only paid out for the first time after 13 years to 20 years of employment. The workers could draw salaries, and the balance carried a certain interest, similar to the salary withholding system used by companies.

Commercial Law

Ohmi merchants operated according to a policy of small profits and quick returns. Their customers were also merchants, usually wholesalers, and the Ohmi merchants tried to look after their customers’ interest, so as to create a win-win situation.

Once during a business trip, Zenemon Takada (1793-1868), a wealthy merchant, was making calculations at an inn when he realized he had received extra accounts receivable from his customer. He decided to credit the surplus within the same day, thinking they might be in trouble, and walked to the owner’s house late at night in the dark. The owner always told the people he met, so impressed was he by the merchant’s honesty and attitude.

Many stories remain about successes that came about through sterling honesty and loyalty. “Be a trusting person” was one of the requirements as a merchant and for Ohmi merchants especially.

Accounting

Ohmi merchants established a double-entry bookkeeping system to understand the financial health of the group company.

Delivering the Product Nationwide (Logistics)

Ohmi merchants developed new trade areas one after another. They established branches for the transportation of products and also used them as bases for storage. Basically the management policy was decided by the main shop, and other managers were assigned to each shop.

Ohmi merchants carried the products from their home town to sell in other regions of the country, such as in Kanto and Tohoku. With their revenues they purchased other products, mainly agricultural raw materials, which they transported back to other areas such as Kyoto and Osaka for resale. They did business in a manner quite similar to the modern-day sogo shosha, general trading companies.

Diet Austerity

The merchants were mostly self-sufficient in rice and vegetables. However, on special days such as for celebrations and festivals, they would hire a cook and order ingredients from the Nishiki market in Kyoto.

Studying and Learning

“Reading, writing and the abacus” were the three most important subjects of study for merchants. Before entering into an apprenticeship from around age 12, children learned the basics of reading, writing and abacus at small private schools called terakoya. After they joined a shop, the apprentices worked during the daytime and studied at night.

Everyday apprentice chores included cleaning the house, and they learned their tasks by observing and emulating their seniors. The process of becoming a full-fledged merchant was a gradual one. Knowledge was acquired through experience, but they were also expected to develop a flexible mind and be smart, so as to make a positive contribution to society. In addition, when time permitted, they read books, practiced calligraphy and tea ceremony, studied Japanese waka poetry and so on to round out their education, which they saw as a stepping stone to becoming an excellent merchant. Merchants in the region were motivated to focus on education and devoted time and money to it.

The Role of the Wife

The wife of an Ohmi merchant would have been required to be an educated person for the husband, who was away from home for a long time, in order to look after the home during his absence. A wife had the responsibility of disciplining and educating apprentices. She learned a numerous things, studying such various disciplines as calligraphy, tea ceremony and flower arrangement.