The Techniques of Becoming a 100-year-old Company in Japan

CONTENTS

There are many long-lived companies in Japan. The number of them is the highest in the world! The number of companies that have been in business for more than 100 years was surveyed by country. Japan has the highest number of 100-year old companies in the world, with 33,076 companies. This accounted for 41.3% of the total number of companies worldwide that have been in business for more than 100 years, or 80,666. The United States was second with 19,497 companies (24.4%), followed by Sweden's 13,997 companies (17.5%) in third place. What is the secret to this?

By Ryoji Shimada

What is the significance of the number 20,788? It’s the number of companies in Japan boasting a history going back 100 years or longer. According to Tokyo Shoko Research, out of a total of 2,251,071 companies doing business in Japan as of September 2009, nearly 1% have been in existence for more than a century.

One might be moved to wonder “Why so many?” The reason might be attributed to Japan’s geographic situation as an island country, which must have served to prevent foreign military incursions and discourage other outside influences. But perhaps we should leave such discussions to historians or anthropologists. Here in this article, we probe into “How were they able to stay in business for so long?”

It is often said that “hito, mono, kane’ (people, things and money) are the most important factors in running any business. But through the fifth 100-year-old Company Research Convention held this past July in Kanagawa Prefecture, other and more significant factors emerged. Aside from “people,” “fueki ryuko (immutability and fluidity),” “brand” and “iji (pride or earnestness) also loomed as common denominators.

Key Word (1): Immutability and Fluidity

“Let’s establish our immutability!” was shouted in unison by a group of speakers in the concluding presentation. Four presentations were given at the fifth 100-year-old Company Research Convention. Each 15-minute presentation was performed by six or seven speakers who were or are the students of Soushin Juku, a business seminar in Kanagawa Prefecture. Most of the students, mostly in their 30s or 40s, are company executives or in line to become future presidents of small- and medium-sized companies. The school’s one year curriculum, in addition to basic business management skills like accounting or marketing, includes a special group task to look into a long-established company for more than 100 years by interviewing its president or staff members. Through such assignments, the students can find firsthand the technique for maintaining long and continuous business.

Making Customers Happy

The above presentation, conducted by the 75th graduating class, focused on Kashiwaya, a traditional Japanese confectionary maker founded in 1852 in Fukushima Prefecture. Last year’s sales revenues by this company, with 135 employees, was about 4.2 billion yen ($52.5 million). The study group, through its research and interview with the current fifth-generation president, worked out “immutability and fluidity” as a key reason for the company’s longevity. “The current president was warned by his predecessor ‘I will never hand over the president signature seal if you do the same things that I did.’” The group’s presenter introduced this comment from the interview and explained this idea came from the precept, “Daidai Shodai” meaning every successive generation must perform as if it were the first generation. In other words, a new president must blaze a new frontier because when the times change, people and their sense of values change with them. Developing a new product is one thing and cultivating a new sales channels --- like online sales --- is another, but even the company’s flagship product, Usukawa Manju (a kind of red bean paste dumpling), evolves from time to time, such as by slight modifications in taste in response to people’s changing preferences. This is only one of more than 200 precepts followed by the company. “Kyo ga Sogyo (today is the foundation date)” is another important precept with a similar meaning to the above, along with “Fueki Ryuko (immutability and fluidity)” which still resonates in the company.

“Kashiwaya’s unchanging business philosophy is to make tasty products and making customers feel happy,” said the presenter and this, in fact, represents the company’s immutability. Now production is performed by fully automated machines, called the Kashiwaya Dream System (KDS). But the purpose of automation was not cost reduction but rather to make the manju tastier. The president in a newspaper interview was quoted as saying, “People told me a machine-made manju couldn’t beat a hand-made manju. I was so frustrated with that. So I tried to make a machine that could produce tastier manju.” Making tasty products is something the company adheres to even following changeovers in presidents, and its determination to make customers happy is carved in stone.

For over 40 years, an Asachakai, or breakfast tea meeting, has been held at Kashiwaya’s corporate headquarters in Koriyama City, Fukushima, on the first day of every month between 6 and 8 am. Participation is free and participants can enjoy freshly-made confectionary with a cup of tea. Only one rule applies: The participants must offer joyful greetings by first saying “Ohayo! (Good morning)” and afterwards “Ittekimasu! (I am leaving).” The Asachakai has become a precious venue where the various people who attend can feel a sense of community. It is especially appreciated by those living in single households.

After the March 11, 2011 earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster, Asachakai meetings were suspended for the remainder of last year. But with the growing expectations held by many people, Kashiwaya resumed the Asachakai this past February. “The company got lots of media attention. It is a fruit of defiant attitude toward its immutable company philosophy, of making customers happy,” stressed the presenter who concluded, “Let’s establish our immutability!”

Sticking to Its Main Business

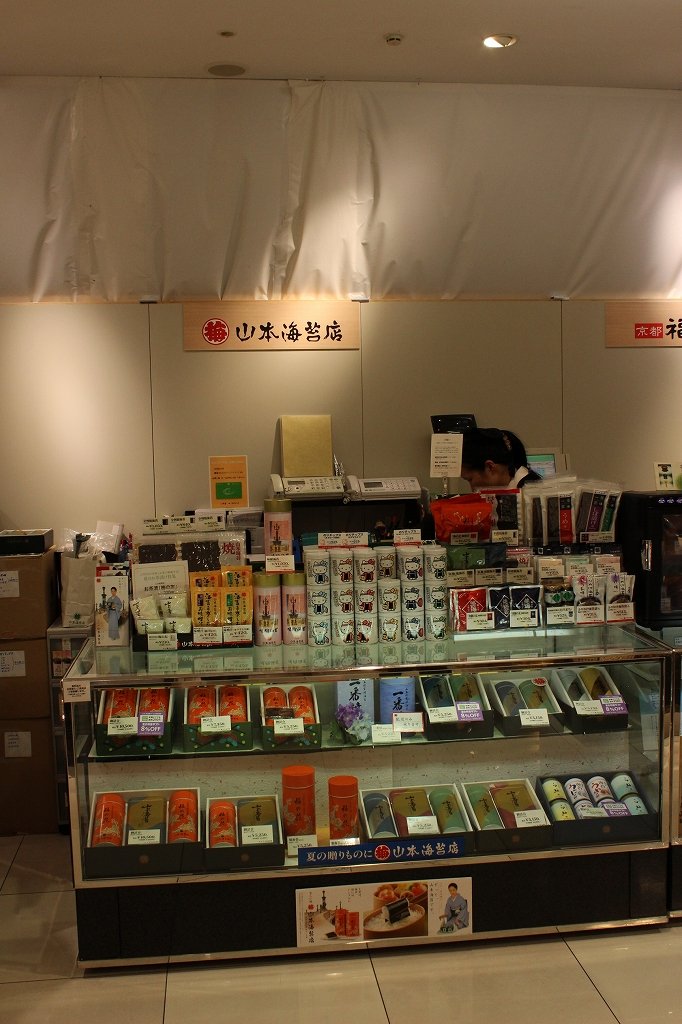

Tokujiro Yamamoto, the sixth-generation president of Yamamoto Noriten Company, seems to think along similar lines. “I am one of the links in a chain,” he says. “My role is to connect to the next link. And I think of what we should not change and what should be changed.” This 163-year-old nori (dried seaweed) maker was the focus of a group in the 76th graduating class. The group’s presentation revealed the company’s immutability: sticking to its main business, nori making, and making customers happy with their good nori, and for its fluidity: not resting on its laurels of brand image but creating new products on its own.

About 80% of the company’s annual sales of seven billion yen ($87.5 million) come from nori-related products. “The nori market is dwindling. But if we can’t earn profits by our main business, we’ll never make profits in other business lines either.” This company president’s firm belief is something not likely to change even when under future management.

What about the fluidity of the company? The second president developed a system of grading nori quality and segmented the products into eight categories, such as for general home consumption, for example, or for gift use. Previously types of nori had not been differentiated.

The president had often said, “Sell things most needed at the lowest prices.” Without a doubt, this customer-oriented attitude must have contributed the company’s long-term success. In 1872, the company developed a new product, “ajitsuke nori,” Japan’s first-ever flavored nori which was even purveyed to the imperial household.

This innovative attitude is seen in other eras as well. In 1965, Japan’s first-ever drive-through shopping window was installed in Tokyo. The idea came from the trip to the US by a company executive who thought, “Motorization will soon come to Japan too. Let’s make nori available even to people behind the wheel.” The drive-through window was finally suspended in 1991, but represents a good example of the company’s “fluidity.” The group’s presentation paraphrased their immutability and fluidity by saying, “Yamamoto Noriten, generation by generation, has been striving for better nori making and trying to sell products in ways that make customers feel grateful. Also the company allows its business style to evolve with the changing times.”

Key Word (2): Hito (people) and Brand

Hito or people are undoubtedly important factor in running a business. I believe no one denies that. The business is run by the staff and the company’s trust is built up by its people. Difficulties are overcome by people’s strong determination, and so on. People play a crucial role in business. And in fact the third presentation, done by a group in the 74th graduating class, revealed this fact in a unique example.

Taken Over Isn’t Necessarily Over

The group’s focus company was Bunkyodo, a nation-wide retailer founded in 1898 mainly selling books. The company employs some 400 staff members with annual sales of 37.5 billion yen ($469 million) as of 2011. This century-old company had been growing yearly until 2004, when annual sales reached nearly 60 billion yen ($750 million) at over 225 stores. Since then sales declined and a number of stores were closed, and finally the company was bought up by Dai Nippon Printing, a major printing company in Japan which now holds 51% of the company shares. The point is even after the company became a subsidiary, it has retained the same president and the same company logo.

“One executive from Dai Nippon Printing was appointed to our board, but we are able to do our business without their interference,” a presenter related the comment by Bunkyodo’s previous president Kinya Shimazaki, who is now the senior advisor. The group’s presentation raised Shimazaki’s agreeable personality as a key to the smooth buyout.

“Even replying to an immediate invitation, he attended a wine party in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture from his home in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture and came back on the same day for another appointment,” the presenter raised, as one typical example of Shimazaki’s sociable character. The group posed a question to the audience whether this company, even after the buyout by the printing company, can be classified as a century-old company. The group’s answer was “yes,” and raised other examples such as Kongogumi. This Osaka-based company, known for building temples and shrines, was founded in 578 AD, more than 1,400 years ago, making it perhaps the oldest company in the world. In 2005 Kongogumi became a subsidiary of Takamatsu Corporation, a major construction company. But even after the buyout, the company’s brand and their group of artisans remained on board.

They also raised an overseas example, Ladurée. This renowned French luxury brand of cakes and pastries was founded in 1862, but taken over by Groupe Holder in 1993. Following the takeover, the company began an expansion drive, setting up pastry shops and tea rooms on the Champs-Élysées in 1997. The presentation was concluded with the summary, “People, together with a functional organization and its beloved products (or services) and a trusted brand are important for continuous business, and if those factors are allowed to remain intact, even if the corporate governance has changed, the company can be categorized as a century-old company.”

Whether a takeover spells the end of a company’s history or not, the audience agreed that people are of the utmost importance. The group discussion session came after the four presentations and there were many opinions voicing such importance.

“There is a trust among our customers toward our president. Thanks to his good and cheerful personality, customers buy our boxed lunches regularly. He seems to put customers before profits,” said Hiromi Saito, an executive of a boxed lunch producer. Toshio Yanai, an executive at Nihonkikaku, computer-related servicing company, said, “Every day we face computers, so we intentionally go out of our way to make personal contacts. In addition to social parties, we cultivate rice fields or perform volunteer work on weekends to deepen ties between our employees. It took me 25 years to understand the importance of human bondage.” The company’s president also introduces his notion on its website, writing “Humans are the most important assets and treasure of our company.” The other people in the audience also commented, “Showing gratitude to our staff even more than to our customers will create a good atmosphere inside a company. It should be a prerequisite for continual business.”

Key Word (3): Iji (Pride or Earnestness)

In the group discussion, one different but candid opinion emerged. “I think I find the idea of ‘immutability and fluidity’ is somewhat high-sounding. There is a saying, ‘Ishi ni Kajiritsuku (to carry through one’s intention at any cost).’ You must have this kind of spirit or determination for business.” This iji or proud attitude was emphasized in the last presentation by the group in the 73rd graduating class. This group focused on another Japanese traditional confectionary maker, Seigetsudo Honten, based in Ginza, Tokyo. Founded in 1906, the company seems to have its own immutability and fluidity. On its website, you can find their two mottos which sound like their immutability and fluidity: “Making customers feel happy with our seasonal confections,” and “Ichidai Ikka (one generation for each confectionary),” which means non-reliance on one’s predecessor, through creation of one’s own confectionary. But the group dug up iji as an important key word in the course of its research.

The group presentation started with the word, “Ginza.” Ginza is known as an upscale area of Tokyo with numerous department stores, boutiques, restaurants and many famous domestic retailers. Ginza is the No. 1 commercial district and boasts the highest property values in Japan. But this district is rather open to outsiders. “If you want to come, we welcome you.” With this kind of attitude, Ginza accepts newcomers. Because the business environment is highly competitive, keeping business alive here gives a sense of iji or pride to a company. With those successful companies, the Ginza brand name is elevated.

This sense of iji is needed to overcome another word raised by the group, which is shiren (ordeal). “During the company’s 105 years of business under four presidents, they have overcome numerous ordeals,” noted the presenter, who raised several examples: the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923; Japan’s defeat in World War II; a major decline in the customary practice of exchanging gifts; the emergence of western-style confectionaries or other types of sweets, and so on.

This attitude of iji should originate from a company’s motto. If the company’s iji or pride is flawed, such as an attitude of trying to make profits at any cost, or in extreme cases even by breaking the law, its business can’t be sustained. In this confectionary maker’s case, the abovementioned “making customers feel happy with our seasonal confections” is the motto and the source of its iji.

Having Good Mottos and Immutability

The Japanese word rinen translates as “motto.” It’s a word that’s often mentioned as an important element for running a business. The rinen is first and foremost of the company’s raison d’être, which should be immutable.

After the group discussion, some groups presented summaries of their discussions. One member of the audience said, “We discussed this topic and concluded that we should base all conduct on principle.” Then, as a member of Rotary Club, he introduced the club’s philosophy. “Is it the truth? Is it fair to all concerned? Will it build goodwill and better friendships? Will it be beneficial to all concerned?” Rotary Club members, in respect to thinking, saying or doing, should consider those four questions. He also introduced Japan’s Ohmi merchants’ management philosophy, “Sanpoyoshi,” which was introduced in the two previous issues of Japan Close-Up. The word refers to a win-win business relationship that realizes “good seller, good buyer and good society.”

In this way, the mottos should be effective ones because they will permeate throughout the company and are therefore strongly connected with the conduct of each and every employee. To summarize this fifth 100-year-old Company Research Convention, “immutability” as the company’s raison d’être is an immutable kernel. “Fluidity” is the prerequisite to adjust to changing times, perhaps by adoption of some innovative idea or new challenge. And of course “people” are important, simply because they are the players needed to run a business. But people need “iji” to stick to the above “immutability and fluidity” for business continuation.

“‘Business is continuation’ is first and foremost of what our school teaches students,” said Takayuki Saito, president of Soushin Group. This business school operates a one-year seminar called “Soushin Juku” which instructs business executives, including company presidents and vice-presidents, how to run their company well and keep their business going. The school also teaches various business skills like accounting, business manners, sales or administrative training, and others. But Soushin Juku is the school’s prime activity and since 1994, more than 500 people have graduated from its programs. Most of them are current presidents or future presidents of small- and medium-sized companies in their 30s or 40s, but their type of business varies from IT companies with more than 600 staff members to a family-run businesses like a barber shop or noodle restaurant. The juku operates four terms per year, with each class composed of six or seven students.

“We once had more than 10 students, but it turned out that was too many. The bonding and relationship between students didn’t deepen,” Saito recalls.

To deepen the relation among the students is very important as they learn from each other and propose solutions to one another’s business problems. “They are forced to disclose every nook and cranny of their company, including the profit and loss statement or balance sheet. Without a relationship based on trust, a student can’t be fully open to the others,” Saito points out.

Of course the students also learn the basics of running a business in a manner similar to what is taught at an MBA program, including accounting, marketing, vision, strategy, risk management and so on. But the second half of the one-year curriculum starts with learning-from-each-other sessions by disclosing each other’s current problem and working out solutions one by one.

“Sometimes the cause of the problem is not related directly to the company per se,” Saito said. “A company owner might have some issue with his wife or wish to let his son take over the business, and so on --- matters for which a business consultant can’t always provide advice. This sort of problem can’t be exposed and resolved without full trust between the students.”

Once every month the students meet and study for a full day, and are given a task each time to finish by the next meeting. The biggest task is to research a century old company and investigate its knack for business continuity. This is a group task and the result is shared only within the group. It is a waste. They began to share the precious knowledge for the longevity of a business with students in different terms. So the 100-year-old Company Research Convention was created and by this, students or graduates can learn others’ results through research and deepening their understanding of knowledge. “There are not many essential factors seen at those century-old companies,” said Saito, who explained several points.

“First of all, they treasure their company’s immutable philosophy and stick to it. Secondly, fluidity is important to adjust to a current trend. That is, namely, immutability and fluidity. And ultimately, a president’s personality counts for a lot. His or her behavior and sense of humanity are always important.”

According to an article in the Yomiuri Shimbun of July 8, over the last decade in Japan approximately 650,000 small- and medium-sized companies have gone under, resulting in the loss of some 3 million jobs. Saito believes that “Revitalizing those small- and medium sized companies will lead to the creation of regional employment and prevent a hollowing out of industry in Japan.”

One thought on “The Techniques of Becoming a 100-year-old Company in Japan”