The Magic of Leaves: Business of Selling Leaves in Japan

CONTENTS

The producer who gave purpose in life and independence to senior citizens, and vibrancy to a depopulated area

Even after turning 100 years of age, if people can find “the joy of having a role,” new flowers will continue to bloom throughout their lives. Once senior citizens understand that there are things that even they can do, the depopulated areas in which many of them live will be revitalized. Residents will also have confidence and pride in their town, and start wanting to spread word of their town further afield. Doing this will energize their town even further – an upward spiral effect.

Just such a town lays nestled in the hills of Tokushima prefecture. The man who produced this revitalized region and gave purpose in life to its senior citizens is Tomoji Yokoishi, the father of the leaf business. The musical “A New Life” has enjoyed a long run of 26 years in the Kamikatsu town theater, and the show continues to run…

Passion moves people and creates new enterprises

Cultivation of mikan, one of Kamikatsu's main agricultural products, suffered a heavy blow in 1981 when the area was hit by a cold spell. Believing that carrying on as they were would ruin both the farming industry and the farmers’ way of life, Yokoishi desperately tried to persuade the farmers to switch to cultivating light vegetables. However, as Yokoishi wasn’t originally from the town, the farmers just wouldn’t lend their ears to this “outsider.” Depopulation and societal aging had become serious social problems in Kamikatsu, with young people leaving to continue their education or to find employment, which was in short supply in the town. All the farmers were doing was whiling away time, Yokoishi recalls.

But wanting to provide the farmers with an income as soon as possible, Yokoishi engaged franticly in light vegetable cultivation, and sales gradually started to increase. However, this didn’t work as an impetus to support the farmers’ way of life and wasn’t enough to restore their confidence and pride.

One day, in 1986, Yokoishi found inspiration while eating in an Osaka sushi restaurant: leaves that would save the farmers and become a business with annual sales of 260m yen. He saw a young lady remark of the Japanese maple leaf used in the restaurant as a tsumamono (decorative food accompaniment), “So pretty and cute. Let’s make a flower pressing!” with which she wrapped the leaf in a handkerchief and took it home. Yokoishi’s instincts told him, “This could be a winner!” These leaves could give people the inspiration and passion to want to do something – something that would change the town’s economy and the direction of the aging farming community. A leaf business would also provide a link to the utilization of local resources, as Yokoishi had always believed that occupations could only be long-lasting if they competed using local things.

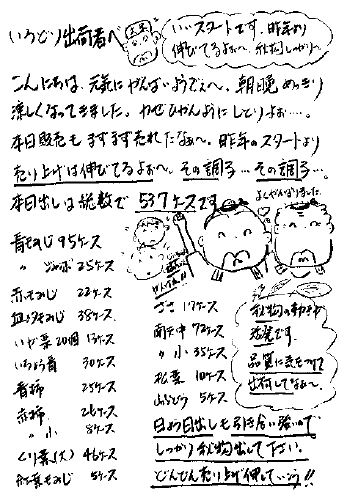

Certain that leaves would work as a business, Yokoishi quickly gathered the elderly farmers together and told them, “From now on, we’re going to run a business selling leaves, so I’d like you to start harvesting them.” However, all the farmers responded, “Leaves won’t work as a business; you can’t sell something that can be found anywhere!” Despite this, a few older ladies thought, “Well, we don’t know if we don’t try. Let’s just try it. We can’t carry on as we are!” and agreed with Yokoishi, and so the leaf-based business Irodori Inc. started in 1986.

However, even though there was demand for tsumamono, sales didn’t come that easily. This was because Yokoishi was trying to run the business without understanding the market. Just because maple leaves are used as a food accompaniment, doesn’t mean one can just pick some leaves growing nearby, put them in a tray and sell them. With that, Yokoishi went to high-class Japanese restaurants where leaves were actually used and tried asking the restaurants about their leaf suppliers, methods, and other questions. However, the restaurants wouldn’t give out information akin to trade secrets so easily, and Yokoishi ended up being turned away. That’s when he came up with an idea: why not go to the restaurants as a customer?

Subsequently, Yokoishi began a pilgrimage to high-class Japanese restaurants. Due to his passion and faith that a leaf business was viable, almost all of Yokoishi’s earnings ended up disappearing at the restaurants. It was well worth it; the restaurant owners and chefs started telling Yokoishi about the kind of leaves they preferred and how they used them. With that, Yokoishi made some adaptations to his operations, such as standardizing the leaves, paying attention to quality control, delivering leaves at the right time, and improving their appearance. As a result, orders started coming in.

According to an elderly female farmer, “Wondering what you’re going to do each day is tough. I enjoy every day because I have something to do.” Another states, “I want to deliver great produce to the customers straight away! I’m busy, so I don’t have time to get sick.” The farmers are said to be lively every day and work with smiles on their faces.

The moment when flowers bloomed among the leaves

Leaves are not the kind of product someone will buy if a daily quota is delivered, nor can they be sold just by lowering the price – and they don’t keep. Another characteristic of leaves is that if they lack even a little bit of color, the food ends up looking unappetizing and the leaves are worthless. That’s why Yokoishi came up with the idea of introducing PCs to all the farmers to ensure that the necessary products reached the people who needed them in a timely fashion. Although this idea met with strong pessimism, Yokoishi was confident, thinking, “If you give a PC to someone with no use for one, it’s no more than a box. But if you get them to understand why it’s necessary, what benefits it has, and teach them an easy-to-understand way of using it, they’ll find there’s nothing quite so convenient.” Yokoishi was certain that the farmers would understand this.

In addition, Yokoishi also thought that if the PCs provided information that made the farmers think “I want to see that!” they would definitely want to use them. These days, tasks such as orders and delivery confirmations are conducted using tablet devices. As a result, Irodori Inc., which started out with just four farmers in a town where one of every two people was a senior citizen, currently enlists 200 farmers to deliver 320 varieties of leaves and blossoms.

The secret of Irodori’s success: discovering a “place” and providing a “role”

Yokoishi believes everyone has a role and can be useful to society. That’s why there’s a stage somewhere on which each of us can play a leading part. This way of thinking is the secret of the leaf business’ success, which also leads to regional revitalization, Yokoishi says. Or to put it in other words, “purpose in life” and “independence”. It’s not the case that senior citizens should act “elderly” and take it easy watching TV. However old people get, if there’s a role for them to play and a place to play it, they can live life with vibrancy.

What’s more, Yokoishi operates the business on a personal level with the individual farmers. He can recognize all of their faces and also understands matters such as their living environment, which farmers get on well with each other, and which farmers – in a good way – might consider themselves as rivals. That also allowed him to create good competition between them. His method was to ensure the farmers could see how much each of them had sold and their ranking by checking it daily on their PC. But he didn’t merely want them to compete against each other; he also wanted to nurture their sense of challenge. In addition, Yokoishi understood that he might burden the farmers with more than they were comfortable with if he asked them to do things unilaterally. Thinking about how to have the farmers continue working for longer, Yokoishi adopted a management strategy whereby he proactively gives work to those who want to do it. Doing this also allowed him to definitively work out their production volumes. Of course, Yokoishi doesn’t forget to make follow-up calls on the farmers. He also communicates with them frequently by fax – one-line messages such as “That’s great! Well done.” This helps give them the confidence that even they can do a good job. Being appreciated by others makes people happy. As a result, a trusting relationship has developed between Yokoishi and the farmers. At times when Yokoishi can’t avoid having to ask for higher volumes, the farmers now say to him, “Well, since it’s you…” and agree willingly.

What is "tsumamono"?

What is the Japanese culinary item tsumamono? Tsumamono are leaves or blossoms that accompany dishes to accentuate the food and produce a sense of seasonality. Tsumamono are not just for looking at and enjoying the food and season; their antibacterial action also gives them a practical role in raw dishes such as sashimi. Leaves such as bamboo grass and maple, and blossoms such as mahonia and plum are often used. In addition, tsumamono are also used during festivals and other events.

One leaf that changed a farming community’s mindset

If something interesting gives them confidence and purpose in life, people behave actively. While still cherishing the sense of the seasons, some of the farmers have now also started getting involved with the marketing of their top-selling leaves. Yokoishi says that doing something different also seems to be reactivating their minds. In addition, in order to harvest better quality leaves, it seems some of the farmers have started devising twists when planting trees, such as selecting areas less likely to be affected by natural hazards, or by growing them in glass houses. One such farmer really surprised Yokoishi. When an official from the agriculture ministry came to observe the business, an elderly female farmer said to him, “I heard [former French] President Chirac is going to visit Japan. If you have a banquet for him, please use Irodori.” The farmers had started to think about their work in terms of news and events in wider society.

Why Irodori’s status as market leader is unchallenged

Yokoishi doesn’t treat things in his leaf business as trade secrets. He says, “As Japan is a land of abundant nature, the same types of leaves could be raised anywhere in the country, so leaf businesses could operate anywhere. Perhaps that’s why so many people from across the country have come to observe us. They try to run the same type of leaf business, but strangely, it doesn’t go well for them. Although our industry sales volumes aren’t high, Irodori Inc. has always held an 80% market share. We’re Japan’s number one in terms of tsumamono production volume.” Yokoishi says the most important reason for Irodori’s success is awareness of the business’ purpose. In short, “It’s not about trying to make money,” he says. The origin of the leaf business was Yokoishi’s passion to do something for the town that would make it a place people could live, and to help the troubled farmers. From this, a trusting relationship developed between Yokoishi and the farming community. That’s why, as Yokoishi says, “I’m confident that Irodori definitely won’t lose to the others. We don’t think that it’s okay just to make more and more money.” Actually, while some farmers are energetic, enjoy the work, and want to do more and more, others want to do a more moderate amount in view of time and physical restraints, reasoning that even doing just a little is of benefit to the town. As a result, while some farms are said to earn a million yen per month, others earn a few tens-of-thousand.

Trainees from all over Japan and observers from all over the world

With the objective of raising successors to the business, a cabinet office regional social employment creation enterprise, “Community-based internship training,” was established in the town of Kamikatsu. In the last 18 months or so, around 240 people have attended the training. One of the trainees, a person in their 40s who had made a decision to farm leaves for business, was asked by the farmer who had guided them during training, “Did you come to Kamikatsu to try and make loads of money?” to which the trainee replied, “No, if I could make enough to live while avoiding death, that would be fine.” The farmer smiled and said, “If that’s the case, it’ll work out. You’ll be fine.”

The number of observers who come to the town also increases year-on-year. 1,410 observers came in 2002. This figure had grown to 3,957 by 2006. And they don’t just come from across Japan – observers have come from the Philippines, Myanmar, Panama, Mexico, and recently, from Bhutan, too. The count currently stands at 36 countries across the world.

No. 1 in Japan?! The birth of a town of lively senior citizens

Kamikatsu is said to be Japan’s number one town in terms of having lively senior citizens – so much so that the municipal old age people’s home was scrapped in 2007 due to lack of residents and was replaced with a non-governmental facility that recruits its residents from across a wide area. Yokoishi says that it is the manager’s job to prepare a stage that meets each of the three elements for human vibrancy – role, appraisal, and confidence – and to believe that anyone can play a part. Yokoishi stresses that if you can build a stage where senior citizens can perform, any region at all can attain everyday independence and vibrancy, which will revitalize the region and, as a result, enrich it economically as well.

Kamikatsu's leaf business is a good example of regional revitalization and a solution to the problem of societal aging. The senior citizens of Kamikatsu have purpose in life and awareness of their roles, they earn an income, and they pay taxes. As they are healthy, their medical and nursing expenses have decreased. Looking at Kamikatsu, one can see ideas for solutions in towns which have aging and depopulation problems. One can also find clues for a solution to bonding together people and societies.

A non-fiction film has been made about the business of selling this leaf for business. You can watch it on YouTube.

What kind of town is Kamikatsu?

Around one hour by car from the center of Tokushima city, Tokushima prefecture, lays the town of Kamikatsu, surrounded by 1,500m-high mountains. The town’s administrative area covers 110 square kilometers, close to 90% of which is mountainous forest. The town is the smallest in Shikoku, with a population of 2,000 people living in 854 households. Depopulation and societal aging has progressed in the town, with the ratio of senior citizens standing at 50%. However, the citizens are healthy, with medical expenses per person rated the lowest among all cities, towns and villages in the prefecture.

The main agricultural products are lumber and unshu mikan, but all the farmers’ plots suffered severe damage in 1981 when the area was hit by a cold spell. Cultivation of light vegetables provided a means of escaping this tough situation, and the leaf business that makes use of the town’s resources began in 1987. Through a process of trial and error, the business grew to be the largest in town and also gave the senior citizens a purpose in life.

In order to create a sustainable local society, the town was the first in Japan to declare that it was “zero waste” and would produce no trash by 2020. Currently, garbage disposers are in place at almost every household in the town, with trash sorted into 24 different types for recycling. As a result, around 80% of trash is recycled and the amount of trash produced is overwhelmingly lower than the nationwide average. In addition, the town has switched from thinking of itself in terms of an economic society (gross domestic product), as it previously had, to the idea of a happy society (gross domestic happiness), with the aim of building the most beautiful town in Japan. To that end, a team of observers from the kingdom of Bhutan, said to be the world’s happiest country, also paid a visit to Kamikatsu.