Marcos Bezerra Abbott Galvão: Ambassador of Brazil to Japan (current Brazilian Ambassador to the European Union in Brussels)

“We have been working together for more than 100 years”

By Ryoji Shimada, staff writer

Brazil, with its relatively young population of nearly 200 million and rapidly growing economy has overtaken the UK to become the world’s sixth largest economy after the US, China, Japan, Germany and France. There are even more expectations ahead of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games, to be hosted by Brazil. But, from Japan, the country is practically on the opposite side of the globe. Geographically, few other countries are further from Japan than Brazil. It is natural to think that Brazilians must feel distant from Japan.

“We had better first mention that we feel very close to Japan because of the fact that there are 1.5 million Japanese descendants in Brazil,” said Marcos Bezerra Abbott Galvão, Brazilian Ambassador to Japan in response to a question on the differences between the two countries. His response may have been beside the point, but his eagerness to emphasize the similarities and closeness rather than the differences was clear. “Although there’s a distance of 18,000 km (11,250 miles) between the two countries that requires travel of 22 or 23 hours in the air plus connecting time, we feel very close because Japanese immigrants have a history of more than 100 years and they are an integral part of the fabric of our society and nation.”

Brazil as the Country of Immigrants

The first inhabitants of Brazil were part of various communities of native indigenous people. But after Pedro Álvares Cabral under the flag of Portugal arrived in Brazil in 1500 as the first European, the influx of outsiders has continued for over half a millennium. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, Brazil was a colony of Portugal. During those days the Portuguese brought African slaves to work there. So Brazil had a large influence of African people besides taking in immigrants from European countries other than Portugal, including Spain, the England, Poland, Germany, Switzerland and others. In 1822, the country declared its independence from Portugal and became a constitutional monarchy, the Empire of Brazil. Slavery was abolished in 1888. After that, new waves of migration began from Italy, Lebanon, Syria and Japan. Currently, the country boasts a vibrant, multi-racial society.

On this point Ambassador Galvão commented that, “After all there are no Brazilians and non-Brazilians. It is a nation of immigrants and a multi-cultural and multi-racial country.”

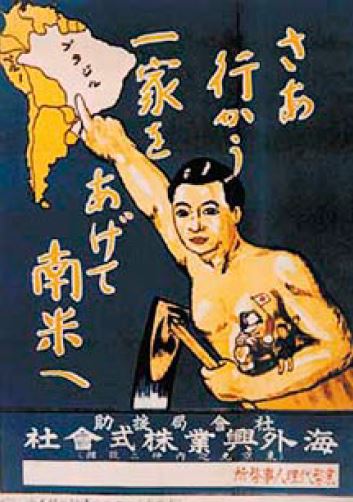

The Arduous History of Japanese Immigrants

Japanese immigration to Brazil is a relatively new phenomenon compared with the country’s other flows of immigrants. In the process of the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century, Land Tax Reform was enacted by the Japanese government in 1873. This major restructuring of the previous land taxation system established the right to private land ownership in Japan for the first time; but unfortunately due to the system’s far-reaching impact on Japan’s social structure, many farmers became impoverished. The idea to go abroad and come back with money must have been seen as an appealing alternative. Brazil, at that time, was suffering from severe labor shortages, especially in the farming industry after the abolition of slavery. Both sides found a communion of interests.

In 1908, the first contingent of Japanese emigrants, numbering around 800, departed from the port of Kobe and after a 50-day ocean voyage arrived at Santos, Brazil. There, they were faced with a harsh reality. Demanding labor conditions with low pay caused some of them flee. Living in an undeveloped and harsh land, caused many to suffer from food poisoning or contract tropical diseases such as malaria. Soon enough, however, some of the more successful immigrants joined forces and gradually built up their livelihood. They published their own Japanese newspaper and set up schools for their children.

During the presidency of Getúlio Dornelles Vargas from the 1930s, a policy of forced assimilation and nationalization was imposed over every immigrant community, including the Japanese. During these years, foreign-language instruction and publications were banned. In addition, after the start of World War II, the severing of diplomatic relations between Brazil and Japan made immigrants’ lives even worse. Draconian measures were imposed against the Japanese, forcibly confiscating their assets and properties. But after the war, in 1951, as diplomatic ties were resumed, so the immigration currents did. Hearing about the austere postwar conditions back home in Japan, many of the Japanese immigrants decided to stay permanently in Brazil.

Those new immigrants initially came as farmers and grow vegetables to supply the rising demand for food from the growing urban populations in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, explained Ambassador Galvão, adding that, “Very early on, they began to work in agriculture and they developed their own land and cultivated vegetables and fruits. By that they managed to help change the diet of Brazilians, with the introduction of fruits and vegetables not known in Brazil. Kaki, for instance.” Kaki, the Japanese persimmon, is now a popular fruit among Brazilians. Fuji ringo, a variety of Japanese apple, is another popular item also introduced from Japan.

![The very high proportion of beta-carotene [vitamin A] makes the kaki fruit a valuable source of nutrition.](https://manabink.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-very-high-proportion-of-beta-carotene-vitamin-A-makes-the-kaki-fruit-a-valuable-source-of-nutrition..jpg)

Although currently around 25% of Brazil’s GDP and 36% of its exports are generated by agriculture and food processing, now the third and fourth generations of Japanese descendents in Brazil play other important roles in the Brazilian economy and various fields of society. Shigeru Fujita (a pseudonym), who after the war emigrated from Nagano Prefecture to Brazil in 1956 while in his 20s, is one of these successful figures. Fujita presently lives in a four-story condominium with an outside swimming pool, in a posh district of Sao Paulo. Speaking with justifiable pride, he said, “When I first came here in the 1950s, I started work practically with my bare hands, first as a farmer and then as a businessman. I opened up a stationary store and became successful.”

Japanese Descendents Highly Regarded

During the interview in his office at the Brazilian Embassy, Ambassador Galvão commented on the perception of these Japanese descendents by the Brazilian people: “Japanese descendants in Brazil are highly regarded. They have managed to adjust and integrate well into society. At the beginning it was not easy. They had to work at heavy labor like agriculture, mostly in the interior. Then they expanded into services and moved into cities. They gave great priority to the education of their children. The more educated, the more their children rose socially. We have leading Japanese descendants in all sectors of our society --- politicians, medical doctors, lawyers, military officers --- everything. So there is great admiration for the Japanese people.”

He then gave the example of Juniti Saito, the current commander of Brazil’s air force. Born in 1942 as the son of first-generation Japanese immigrants, Saito is the first Japanese-Brazilian to reach the highest rank in a branch of the Brazilian Armed Forces.

Traits and Education Behind the Success

Ambassador Galvão attributes the success of the Japanese descendants in Brazil to their traits and attitudes. “The feeling Brazilians nurture toward Japanese is of admiration not only for the seriousness with which they conduct their tasks but also for the way they look after the education of their children. The Japanese parents that immigrated to Brazil must have been concerned about their sons and daughters. They probably wanted their children to have the possibility to live a more comfortable life than they did. I think Brazilians closely observe the discipline, determination and honesty with which Japanese developed their place in our society.”

Fujita is no exception. He devoted lots of effort to his children’s education and both of his two offspring have become doctors. Fujita doesn’t deny the achievements of Japanese descendants, which he believes are due mainly to their characteristic hard work: “Those who remain in Brazil and become successful have tenacity and have always tried to do their best.”

Differences Make a Good Combination

Pedro Macedo from Teresina, Brazil, has lived and studied in Japan since 2004 and was hired by a Japanese company last year. He praises the perfectionism of Japanese and agrees it is part of the reason behind their success. He also believes that the differences between Brazilians and Japanese complement each other: “Brazilians are louder, noisy and extroverted, while Japanese are more discreet, and a little more reserved. The ways of establishing communication or contact are different, but those differences make up for a good combination.” He thinks Japanese are sometimes too discreet or circumspect and so avoid pointing out when something is wrong: “They read the air or ambience too much and turn a blind eye to something unpleasant. But Brazilians are more active. They are willing to rectify something by themselves and even fight alone if they think there is something wrong.”

This complementary relation works in the business world. Yoshihiko Yamamoto, president-director of the insurance broker Toyota Tsusho Corretora de Seguros said in an article titled The Japanese work ethic and Brazilian flair combine for an unbeatable team, published on September 7, 2012 in The Japan Times, that: “When I came to Brazil, the quality level of our employees was just average. I made sure they learned the Japanese style of business and work. This, combined with their Brazilian ingenuity and progressive attitude, has been the biggest contributor to my company’s growth here these past few years.”

Ambassador Galvão also vouches for this good chemistry: “We have been working together for more than 100 years, so you just have to ask both Brazilians who work in partnership with Japanese and vice versa and they will tell you that we work very well together. Japanese companies have had a strong presence in Brazil since the 1950s. They are all successful and I don’t know of any major Japanese companies that left the country. So once they are there, they are happy to be there.”

Chances for Japanese Investment

Overall bilateral economic relations have been growing, as borne out by statistics from the Ministry of Finance. Japan’s exports to Brazil doubled from $3 billion in 2006 to $6.1 billion in 2010. Imports from Brazil also doubled during the same period, amounting to almost $10 billion in 2010.

Entry into the Brazilian market has been also brisk. According to the Brazilian Central Bank, Japanese direct investment in Brazil reached $7.5 billion in 2011, a three-fold increase from the previous year. This puts Japan in the fourth place as an investor, after the Netherlands, the US, and Spain. The increase was attributed mainly to Kirin Holdings’ takeover of the Brazilian Schincariol brewery. But the investments also spanned a wide range of products, from automobiles, iron and steel and mining to paper manufacturing.

However Ambassador Galvão laments the still relatively low presence of Japanese investors in Brazil especially when their number is compared with the overall amounts of investment. He wishes that more companies would decide to open offices there: “The number of companies is still very limited. There are more than 20,000 Japanese companies currently operating in China, but in Brazil, a few hundred only. I think more companies should come including small- and medium-sized companies.” He continued: “One positive aspect for Japanese companies planning to invest in Brazil is that there has been a robust relationship between Japanese and Brazilian societies. Brazil is expanding consistently. We have a very large domestic market comprised of 194 million people. In the last 10 years some 30 to 40 million people have risen from poverty to the middle-income bracket. There are many opportunities and demands for investment.”

Currently the Brazilian infrastructure fails to meet the demands of its ever-growing economy, especially in the field of transportation and energy. These logistical gaps are more visible than ever ahead of the upcoming FIFA World Cup and Olympic Games. In order to address these challenges, Ambassador Galvão counts on Japan’s contribution: “The Brazilian government and society know that we have to strengthen our innovation capability. Japan is a technological world power. We have a relationship of trust between the two countries and their companies. We very much want Japanese companies and institutions to be part of this innovation.”

Learning from Brazilian Optimism

Japan can contribute to Brazil with technology and innovation. It is easy to imagine. But is there anything Japan can learn from Brazil? “Soccer is an area in which perhaps we have transferred too much technology already,” the Ambassador remarked half-jokingly. “Japanese are now very strong, both female and male teams, more and more. Also Brazilian music in general is appreciated here. Japan is the largest market for Brazilian music in the world after Brazil itself.” He then mentioned Brazilian optimism, “Brazilians are very optimistic and confident. Even when we had economic difficulties between the 1980s and early 1990s, we never lost confidence in our destiny and ability to advance. This self-confidence and optimism is something that perhaps, I dare say, could be a good influence for our partner, Japan.

“Sometimes I get a sense here, if I may, that there is one aspect which I think could be improved here, that is optimism. Japanese young people have all the reasons, looking towards the future, to have optimism and self-confidence. There could be a positive contamination from Brazilians who face more challenges than the Japanese. We still have some social challenges to overcome and also investment and development trials.”

Perhaps the Asakusa Samba Carnival in Tokyo illustrates some signs of the Japanese longing for that kind of optimism. The event has been held annually since 1981. Now there are many samba festivals around Japan, but this one is the biggest. The venue attracts crowds of around 500,000. Maybe Japanese suppressed feelings and buoyant samba dancing are two sides of the same coin.

A Strong Bond between the Two Countries

“I went to the Asakusa Samba Carnival which was attended almost entirely by Japanese. I was very impressed with the quality of the samba groups here. Many of them went to see the carnival in Brazil,” the Ambassador remarked on the celebration. “I met many people who have relatives in Brazil. An uncle went to Brazil, a cousin went there, friends went there, etc. There are these human ties that exist between our two countries and that is, I think, a relevant way of creating bonds between the two societies.”

On the first of March, 2012, a social insurance agreement between Brazil and Japan came into force. The agreement facilitates the citizen's access to the social insurance system in both countries. Workers that have contributed to any one of the systems can now combine the contribution periods in order to attain the minimum number of years required to obtain the due benefits and payments. Currently around 210,000 Brazilians are living in Japan, making them the third biggest group of foreigners after the Chinese and the Koreans. Considering that China and South/North Korea are close neighbors, the Brazilians stand out as a unique phenomenon. The pension agreement will certainly further enhance the ties between the two countries, irrespective of the geographical distance.