The Best-selling Book in Japan: Saka no Ue no Kumo (Clouds above the Hill)

CONTENTS

Giving a New Angle on Japan: “Blockbuster Historical Novel Depicting Japan’s Rise Now Available in English”

By Ryoji Shimada

Celebrated Among Business Managers

“Many business managers or company presidents list Saka no Ue no Kumo (Clouds above the Hill) as their favorite book,” says Yoshikatsu Morikawa, office manager at Saka no Ue no Kumo Museum.

Sure enough, if you do an online search for this book by Ryotaro Shiba, one of Japan’s most renowned novelists, you can easily find many praise-filled references to it by businesspersons. “The book is about military history and [Japan’s] miraculous victory over [Russia] in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The situation is graphically depicted. The decision-making power of Togo Heihachiro and Kodama Gentaro is superb. It is very intuitive. The book is a great masterpiece,” notes an IT company’s president on his blog. A business consultant expresses similar thoughts on her website: “I have had many occasions to talk with company executives and presidents, and many of them told me that Saka no Ue no Kumo is their bible. There must be hints on leadership, decision-making, drive, etc. in the story.” Minoru Mori is the president of Mori Building Company, a major property management firm which built China’s tallest building, the Shanghai World Financial Centre. Yasuyuki Yoshinaga is the president of transportation conglomerate Fuji Heavy Industries, best-known as the manufacturer of Subaru automobiles. Both have publicly stated that the book is their favorite.

Captivated by Characters’ Lives

But the book also appeals to ordinary readers. After all, it has sold around 20 million copies since it was first published in 1972. “It is a story about youths surviving a tumultuous period and confronting difficulties with hope and ambition. I was fascinated by these characters’ ways of life,” says a retired man in his 60s. Yoshihiro Kawashima, a 33-year-old curator at the museum, explains the book’s appeal: “It is very interesting to read about not only the main characters but many others, including ordinary people, striving to attain their high hopes. They all have quite a broad view of the country, too, which is rarely seen among Japanese people these days. I also found it interesting that the lives of university students were very similar to ours.”

Saka no Ue no Kumo Museum is located in Matsuyama City, Ehime Prefecture, where many of the characters actually lived and where many episodes in the book take place. There are museums which are named after authors. However, there is probably no other museum whose name comes from the title of a book. This fact itself demonstrates how popular the book is in Japan. But the number of visitors is another indicator of its popularity. “It is said that a museum of this size can usually expect 50,000 visitors annually. But we aimed at 100,000,” said Morikawa. However, the data shows a far larger figure. In 2009 and 2010, over 200,000 people visited each year. In 2011, the figure went down a little due to the Great East Japan Earthquake, but was still over 160,000. Visitors are relatively mature, in their 50s or 60s, but many younger people can be seen there too. The gender difference is not significant: 55% male to 45% female.

The museum exhibits items related to the characters and stories depicted in the book. To provide a deeper understanding, artifacts and videos illuminate the Meiji era (1868-1912), which is the backdrop of the novel. The museum introduces the book and its appeal as follows: “The novelist Ryotaro Shiba spent most of his 40s writing in order to complete this work. The novel depicts Japan in the Meiji era, when it was heading towards becoming a modern state, by introducing various characters, including the Akiyama brothers Yoshifuru and Saneyuki, and their friend Masaoka Shiki, all natives of Matsuyama. It was the era when [Japanese] people became aware for the first time that, by working hard to obtain qualifications, they could be a doctor, a bureaucrat, or a military leader. Shiki became a journalist and made innovations in modern haiku, tanka, and prose. On the other hand, Yoshifuru joined the cavalry of the Imperial Japanese Army during its early days, while Saneyuki established modern strategies in the Imperial Japanese Navy. They lived through a time of great change when the Russo-Japanese War started.

Shiba said about his novel, ‘The overall theme is, What is it to be Japanese? I wanted to think about it under the conditions in which the characters of this story were placed.’ The novel is full of thought-provoking insights for us living in the modern era.” A 29-year-old woman visiting the museum says, “It was a very dramatic period in history. There were human dramas, and the drama of that historical moment in Asia. The Russo-Japanese War was a war that I don’t know much about. Some people call it World War Zero, because it was the precursor of those other later engagements, and the world was involved in this war - not only China, Japan and Russia, but also France and Great Britain. The Spanish-American War had an influence on Saneyuki. He went to America to observe that war, and he used lessons from that experience to create his winning plan. It is a real international story. It is a brilliant way for Shiba to present it.”

The Book and Its Background

Saka no Ue no Kumo is considered a Japanese historical novel about the Russo-Japanese War. It first appeared as a newspaper serial between 1968 and 1972, and was later published in book form, first in six volumes and later in eight. The main characters are the above-mentioned Akiyama brothers and Shiki, who were all born around the time of the Meiji Restoration. The Restoration led to enormous changes in Japan’s political and social structure, and was responsible for the emergence of Japan as a modernized nation in the early 20th century. In the book, the Akiyama brothers symbolize the new freedoms, the energies released, and the nationalism of post-1868 Meiji Japan. Instead of being condemned to life in the remote castle town of Matsuyama, the two young men are determined to build a Japanese military capable of holding its own internationally. Another character, Masaoka Shiki, is an unconventional poet and a close boyhood friend of the brothers. His singular aim from college days onwards is to be a leading light for the revitalization of haiku. This earns him a solid reputation for having rediscovered and promoted a previously disdained art form. The first half of the novel covers these three characters’ lives, while the latter half starts after Shiki’s death at the age of 35. The story depicts the Russo-Japanese War and the historical background of that period.

The title is derived from those people of the Meiji era who were striving to modernize their country. They had no doubts, only a shared optimism. In the postscript, Shiba writes, “Those optimists, motivated by living in such a period of great change, looked straight ahead as they made their way through life. If they saw a cloud in the blue sky above the hill along the way, they would walk up the hill holding it in their gaze.”

Forty years after it was first published in 1972, an English translation was finally unveiled last December. The introduction, written by Peter Duus of Stanford University, begins: “E.L. Doctorow once observed, ‘Historians tell you what happened; novelists tell you how it felt.’ In this epic novel, Shiba Ryotaro tries to do both,” and describes those days when, “[determined] to avoid the humiliations suffered by their neighbor China at the hands of the Westerners, [Japan]’s new leaders launched an effort to strengthen the nation by learning how the Europeans and the Americans became ‘rich countries with strong armies’ (fukoku kyohei), and within the space of a generation the Japanese accomplished what had taken the Westerners two or three centuries. Their success made possible Japan’s astonishing victory over Russia in 1905. Through the lives of the Akiyama brothers, the novel offers an overview, in fascinating detail, of this remarkable historical transformation.” He also tells how Shiba views the people of those days: “The Meiji era was a ‘bright’ era that produced men of high character. Many were sons of former samurai, uprooted and impoverished by the Restoration, who struggled to make their way in the world despite political and social upheaval.”

Third Attempt at an English Translation

The English translation of the book went through many twists and turns. In fact, this was the third attempt. The first attempt was by an Australian with the initial N. Mr. N lived in the Shikoku region, where Matsuyama is also located. He was so taken by the story that he wanted to translate it. The author Shiba welcomed his effort. But then he asked a major publisher to check the translation, and they found that it needed a lot of editing. There may have been other reasons as well, but in any case, the first attempt fell through.

That was in the late 1970s. The second attempt came more than 20 years later. The Japan Foundation, a government-affiliated public institution, took up the project and formally asked William Naff, professor emeritus of the University of Massachusetts, to translate the work in 2000. But he passed away before it could be completed, and again the project failed.

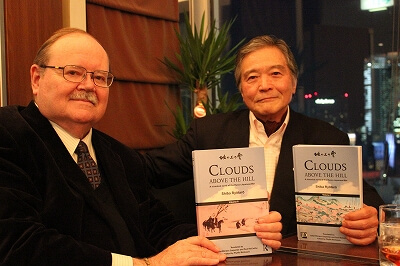

“It is the so-called, ‘Third time lucky.’” Sumio Saito described the third attempt, which he oversaw. He founded a publishing company, Japan Documents, in 2001. Its mission is to introduce little-known but valuable and cherished Japanese publications overseas. His first publication was The Iwakura Embassy. It is a true account of a group of leading politicians on an observation mission through the US and Europe from 1871 to 1873, after Japan’s centuries of isolation. It consists of five volumes and won a major prize in Japan.

“Saka no Ue no Kumo is my next endeavor. It is a masterpiece equal to War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy. It portrays vividly Japanese society in the latter half of the Meiji era and the difficulties people faced then. I have wanted to translate it for a long time.” Saito formally obtained the translation rights in March 2009. In fact, he had already hired a team of renowned translators - Paul McCarthy, Juliet Winters Carpenter and Andrew Cobbing - as well as Phyllis Birnbaum, a distinguished editor, and the team had started working on the project in 2008. Finally the translation was completed, and the first two volumes were published in December 2012. The latter two volumes will be issued later this year by Routledge, a British publisher.

Giving a New Angle on Japan

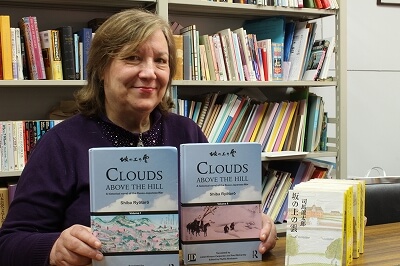

“I really enjoyed translating this book,” says Juliet Winters Carpenter, one of the three translators and a professor at Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts. “I became very fond of Shiba as I was working on it. This is not only a celebration of war or of Japan’s victory. Shiba takes a very long view all the way through. He goes a long way back into the past. He is also looking ahead to the Vietnam War and brings up, of course, the Pacific War. He puts everything into context. But Shiba thought that, after their victory, the Japanese military got onto the wrong track. What he thought was that they became too proud and self-destructive. The army and the navy in the Pacific War almost destroyed Japan.

“That’s why he goes back again and again to the Meiji era, to figure out what happened. How did Japan get on the wrong path? Meiji people were so noble. Nobody told the Akiyama brothers that they had to do things. But they wanted to. They were driven by desire, and made themselves into the best people they could be. At the same time, they built up their country. The mood of the time was very special. That’s what Shiba celebrated in this book. Even though it is about the war, overall the book is very positive. It was a time of hope for the country. It is not about the glorification of war.”

Ryotaro Shiba once wrote, “I can’t help admiring the political and military leaders at the time of the Russo-Japanese War. I could hardly believe that they were Japanese.” Saito has high expectations. “I hope it will make a change in the view of non-Japanese towards Japan and Japanese people.”