What Is Shakuhachi?: The Blue-eyed Shakuhachi Player Who Continues to Create New Musical Instruments

CONTENTS

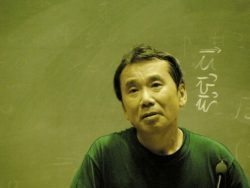

Shakuhachi player and maker John Kaizan Neptune

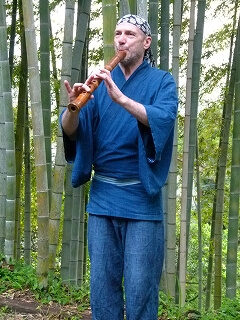

In a house surrounded by bamboo forest in Kamogawa City, which is located in the southeast corner of the Boso Peninsula, Chiba Prefecture, lives a foreigner who unduly suits an outfit of samue robes paired with a tenugui towel. John Kaizan Neptune, who came to Japan 40 years ago, is both a player and maker of shakuhachi ((traditional Japanese end-blown flute typically made from bamboo).

Samue is cotton or linen robes worn by Japanese Buddhist monks when performing labor duties such as temple maintenance. Samue are also worn by shakuhachi players due to the instrument’s historical association with Zen Buddhism.

Tenugui is Japanese cotton towel dyed with a pattern that can be used as a washcloth, dishcloth, headband, souvenir, decoration, and for many other purposes.

Neptune was born in California, a dyed-in-the-wool American. In his younger days, he was so obsessed with surfing that when he continued his education into college, he chose Hawaii University because of the great waves there. So how did such a young American surfing enthusiast become interested in the shakuhachi, and come to lead a life that was inseparable from this ancient musical instrument?

The Oriental Timbre That Touched His Soul

Neptune was born in 1951 into a musical household in Oakland, California. Influenced by his jazz-loving father, Neptune first started out playing jazz trumpet before moving on to playing drums in a rock band. Above all, he loved music; it was fun and cool, and so it was his intention to always keep doing it. The other passion of this vigorous young man, full of curiosity and energy, was sport. At various stages, he gave his all on the baseball diamond and basketball court, but it was surfing that he really fell for – so much so that he gave up his other sporting pursuits. What he liked about surfing was the fact that it allowed the surfer to be free and use his own abilities rather than being a competition with a winner and loser.

Neptune lived in San Diego on America’s west coast, the Pacific Ocean spreading out before his eyes. He would stop by the sea every day after school. His feelings for surfing were growing ever stronger, and so he chose to apply to Hawaii University for the reason that he wanted to go to the Mecca of surfing, Hawaii. His wish came true, and he crossed the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii, spending his days cavorting amongst the world’s finest waves. Meanwhile, his interest in music was also rekindled by an encounter with folk music.

Thinking that he would like to learn something interesting during his college years, Neptune chose to study folk music. While he also played drums in a rock band, Neptune initially wanted to learn the tabla, an Indian percussion instrument. However, even though he was able to study it academically, there were no instructors at the college who could play it.

自宅内の工房には、制作・調律中の尺八や工具が所狭しと並ぶ-1.jpg)

That was when Neptune came across the shakuhachi. Until then, he had been unaware of the existence of such a musical instrument. Back when he lived in mainland America, he had never even seen bamboo; the closest he had come to bamboo was seeing bamboo grass in botanical gardens.

Wind instruments produce sound from the vibrations caused by air flowing through the tube section. However, since bamboo is originally hollow in the middle, there’s no need to bore a hole through it like wood; simply remove any knots and the bamboo can be transformed into a musical instrument just as it is. The shakuhachi is merely such a piece of bamboo with five holes bored in it – a very simple wind instrument.

The first time Neptune heard the sound of the shakuhachi, he was immediately captivated by it. He was entranced by the expressiveness of its rich timbre and abundant variety of tones; while you might think it would produce crystal clear high notes like a flute, it also ranges to saxophone-like husky bass notes.

Neptune was able to learn the basics from Ryo Okano, a Zen Buddhist monk who lived near the university and could play the shakuhachi. It is said that people who pick up the shakuhachi for the first time struggle to produce a note from it. However, Neptune was able to produce a note surprisingly easily. After that, he would repeatedly practice techniques such as how to cover the holes, strength of aspiration, and how to change the scale or expression of a note by adjusting the angle at which his lips touched the mouthpiece. Neptune also gradually grew accustomed to traditional Japanese written music, which has a unique vertical notation.

The Shakuhachi That Expresses “Nothingness” in Sound

For Neptune, the shakuhachi embodies the world of the Orient itself. The Western world is, so to speak, the world of “something.” If there is a space, something can fill it. Conversely, the Eastern world is the world of “nothing.” Spaces and blanks are not entirely filled, but are used just as they are. Neptune sees the tokonoma, the raised alcove in traditional Japanese rooms, as the epitome of this: “For Westerners, the tokonoma is a very curious space. A Westerner would think that not using the tokonoma for something was a waste of space, and would store things or stand a bookcase in it. However, for Japanese, the tokonoma is not a space for filling with things. The space exists just as it is, as ‘nothingness.’ It isn’t a waste of space even without something in it. This isn’t an idea that exists in the West.”

The same thing could be said for painting. In Western art, the entire canvass inside the frame is covered by paint. If any areas were left in their original blank state, people would think the work was unfinished or that the artist had forgotten to paint part of it. On the other hand, blank spaces are fundamental parts of Eastern art such as sumie ink paintings. Here too, “nothingness” is brought to life.

Neptune says, “In the music world, it is the shakuhachi that expresses nothingness.” Certainly, the concept of “ma” (interval) is important to Japanese music. Particularly in the case of the shakuhachi, the moment of soundlessness between tones also forms part of the music as a whole. Moreover, the sound the shakuhachi produces is not just a pure clear tone – “nothingness” is also incorporated within the sound itself. Some sounds, for example, are rather rasping and hoarse.

Shakuhachi used to be carried by priests of the Fukeshu School, a branch of Zen Buddhism that flourished in the Edo Period, and were played as part of the priests’ ascetic training and pilgrimages across the nation. That historical and cultural background was also of interest to Neptune.

“There is a phrase ‘ichi on joh butsu’ (one sound becomes Buddha),” Neptune explains, “It means that one can reach enlightenment by putting everything into a single sound. I don’t think you’d find that kind of philosophy anywhere else even if you searched all over the world.”

To set off on a trip training clutching a shakuhachi and build up one’s ascetic training: Neptune, who was also devoted to Eastern philosophy, became increasingly fascinated with the Oriental values and world of nothingness that were revealed to him via the shakuhachi.

By and by, Neptune grew dissatisfied with his classes in Hawaii. He then wanted to study the shakuhachi for real in Japan. He decided to take a year out from college and apprenticed himself to Genzan Miyoshi, the man who taught Ryo Okano, from whom Neptune had learned the basics of shakuhachi playing in Hawaii. Once again, Neptune set out over the Pacific Ocean, this time from Hawaii to Japan. It was the first time he had ever set foot there.

The Instructor and the Professional Musician

Genzan Miyoshi is a master teacher of the Tozan School of shakuhachi, which bases its activities in and around Kyoto, but at that time, he was still only a young instructor who hadn’t yet turned 30. Later, he would travel to America and Europe to stage the first worldwide shakuhachi concert tour, and also oversee the music for the Japanese synchronized swimming team that won silver in the Sydney Olympics in 2000. Miyoshi willingly accepted Neptune as his apprentice simply because the young American was a budding shakuhachi player, in spite of the fact that Neptune knew almost nothing about Japanese language or culture

While in Hawaii, Neptune had become reasonably capable in the space of a year at getting the shakuhachi to produce notes. He was very keen to show what he had accomplished to his new teacher. Spurred on by that desire, Neptune prepared to face his first practice session. However, before he entered the room, he was stopped by another apprentice who said to him, “Hold on. Before you enter the room, you must firstly sit in the seiza position (sit on one’s heels), quietly open the sliding screen and greet him with ‘Yoroshiku onegai shimasu (formal greeting)’.”

Neptune discovered a fresh surprise upon hearing this. “So the practice starts even before I enter the room,” he thought.

But it wasn’t just practice that was surprising; the Japanese way of life itself gave Neptune one culture shock after another. Everything he experienced was unlike the life he had known previously, from sleeping on a futon laid out on a tatami straw mat floor, to going to a bathhouse and soaking in a hot tub along with other people.

Even in the hot and humid Kyoto summer, Neptune stayed at a cheap boarding house with no air conditioning. Mosquitoes would fly in if he opened the window. Yet if he kept it closed, the heat would be unbearable. There were times when, wiping off the dripping sweat, he would ask himself “What on earth are you doing?!” Although it was certainly not easy living in a different culture, Neptune perceived those experiences positively as something that would teach him endurance.

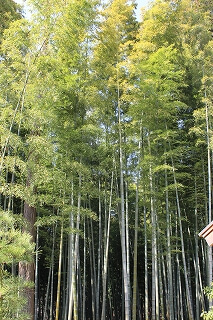

Neptune also first came to know the beauty of bamboo forests from living in Kyoto. Through bamboo forests, he could sense the real depth of the Japanese culture of harmonizing and attuning nature. And the notes from the shakuhachi he heard played in such uniquely Japanese surrounds felt as though they had a whole new layer of breadth and depth. It strengthened his conviction that choosing this path was no mistake.

After his one year break from college was over, Neptune temporarily returned to Hawaii University to get his qualification. However, after graduating, he was back in Japan. He built up his training further in Kyoto and even managed to attain a license to teach Tozan-style shakuhachi. At the same time, he was given the pseudonym “Kaizan” and the American shakuhachi player John Kaizan Neptune was born.

Subsequently, there would be an increasing number of occasions when Neptune was called in as a studio musician, which all started when a certain television program asked him to perform some standard jazz numbers on the shakuhachi. While based on the music of the traditional Tozan School, Neptune constructed a unique musical universe from a new out-of-the-box idea of fusing the shakuhachi with various other musical forms. His work began to draw attention both inside and outside Japan.

The drummer from the band of Herbie Hancock, the famous jazz pianist, heard Neptune perform and told him, “Your music is so full of ‘spirit’. I’d also like to make music like that.” This episode perhaps shows both Neptune’s strong musicality and the depth possessed by his instrument, the shakuhachi.

Feelings Toward Bamboo Poured into Making Shakuhachi

Neptune isn’t just a shakuhachi player; he is also a craftsman who makes his own shakuhachi. For a musician, the quality of his instrument is his lifeblood. As he continued performing, Neptune would grow dissatisfied with the pre-made shakuhachi he was using and was always ordering various things from the craftsman who made his instruments. Thinking it may be quicker just to make his own, he started to try making shakuhachi.

In Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture, where Neptune moved to over 20 years ago, there are many areas with groves of giant timber bamboo – the material used for shakuhachi – so Neptune does not lack for raw materials. However, as the shakuhachi uses the root part of the bamboo, only one instrument can be made from each bamboo culm. As the bamboo roots are concealed underground, you can’t tell whether a certain culm is suitable for making a shakuhachi or not unless you try to dig out the root. What’s more, although shakuhachi generally have seven nodes, factors such as the number of nodes, the spacing between them, girth, and shape are all different for each bamboo culm, so digging out the ideal bamboo is no easy matter. Even if you spent all day searching around the forest, you’d do well to find 10 culms that were suitable for making shakuhachi, and of those 10, only around two would actually become good quality instruments.

Once the bamboo has been dug out, it is left to dry for around two years. Behind his house and in his production workshop, Neptune has hundreds of bamboo culms piled in heaps, waiting for the day when someone will play a note on them as a shakuhachi.

Making a shakuhachi isn’t something that anyone can do. Factors such as the way the embouchure – the mouthpiece that the player blows in to – is whittled, the shape of the tube section, and the way the holes are cut sizably affects the sound produced. You need to be able to play the shakuhachi in order to tune it correctly, so only shakuhachi players are able to make them.

On top of being an excellent shakuhachi player, Neptune is an avid researcher. He developed his own diagram to describe the correlation between tube shape and sound changes, which he utilizes to make his shakuhachi.

Listening to the differences in sound before and after tuning reveals that pre-tuned shakuhachi only produce hoarse and husky tones – even when played by a professional such as Neptune – whereas the shakuhachi tuned by Neptune produce a full and mighty sound.

The quality of that sound gained repute, and now Neptune receives orders for shakuhachi non-stop from all over the nation. He’s also seen an upturn in requests for repairs and adjustments, and a number of shakuhachi are now queued up in Neptune’s workshop, awaiting his care and attention.

Forty years have passed since Neptune came to Japan. He has now spent more time in Japan than America, and bamboo is an ever-present part of his life. He interacts with it as a musical instrument and savors the beauty of bamboo forests. But that’s not all. In early spring, the bamboo shoots that Neptune picks from around his house also make their way on to his dinner plate.

“Good to look at, good to listen to, and tasty to eat: that’s bamboo,” he explains. The good-humored Neptune also jokes that the shakuhachi that are the tools of his trade are also “Just right as backscratchers when you have an itchy back!” More than anyone else, John Kaizan Neptune loves Japan, loves bamboo, and is earnestly continuing his activities to communicate the attractions of this wondrous plant.

Recently, a documentary film "Kaizan Take no Oto" was made about his life with the shakuhachi. If you are interested in it, please watch it.