Understanding "Rongo to Soroban" in English by Eiichi Shibusawa

CONTENTS

- Not only as a business person but as the father of capitalism in Japan

- Eiichi Shibusawa's Early Life

- Publishing "Rongo to Soroban" (the Analects of Confucius and Arithmetic)

- 1) Life and Beliefs (処世と信条 Shosei to Shinjo)

- 2) Rising aspirations and Learning (立志と学問 Risshi and Gakumon)

- 3) Common sense and Habit (常識と習慣 Jyoshiki to Shukan)

- 4) Humanity and Wealth (仁義と富貴 Jingi to Fuki)

- 5) Ideals and superstitions (理想と迷信 Riso to Meishin)

- 6) Character and Cultivation (人格と修養 Jinkaku to Shuyo)

- 7) Arithmetic and Rights (算盤と権利 Soroban to Kenri)

- 8) Jitsugyo and Bushido (実業と士道 Jitsugyo to Shido)

- 9) Education and friendship (教育と情誼 Kyoiku to Jyogi)

- 10) Success/Failure and Destiny (成敗と運命 Seihai to Unmei)

Not only as a business person but as the father of capitalism in Japan

If I were to ask you who you know as a Japanese businessman, who would you name? You might name Masayoshi Son of Softbank, Kazuo Inamori of Kyocera, Konosuke Matsushita of Panasonic, or Tadashi Yanai of Uniqlo. But as of 2021, the most notable Japanese businessman is probably Eiichi Shibusawa. Shibusawa Eiichi passed away more than 90 years ago, so he is quite an old figure compared to the above four, but he is the protagonist of a year-long NHK drama series that has been aired in 2021, and many books about him are selling well. His masterpiece, "Rongo to Soroban" (the Analects of Confucius and Arithmetic) has been published by various publishers and has been sold for more than 100 years.

Eiichi Shibusawa founded Japan's first bank (now Mizuho Bank), a non-life insurance company (now Tokio Marine & Nichido), and more than 500 companies in total. (See the list of some of the companies Shibusawa founded.) Naturally, he ran his own companies, but most of the time, he entrusted the management of his companies to people with management skills. As a result, he has been nicknamed the father of Japanese capitalism rather than a businessman.

On the next 10,000 yen bill

In 2024, he will be the face of the 10,000 yen bill. Despite the fact that it is the most expensive piece of money issued in Japan, he placed great importance on the morality of the Analects. He taught the importance of contributing to society by maintaining a balance between morality and economics. I would like to introduce the essence of this book. If you are a foreigner and want to work in Japan, if you are asked, "Who is your favorite Japanese person?" you can reply "Shibusawa Eiichi" and if you are asked, "What is your favorite book?", you can say "Rongo to Soroban." Then you can impress the people who asked you.

Eiichi Shibusawa's Early Life

Eiichi Shibusawa was born in 1840 in the Fukaya region of northern Saitama Prefecture. His family was a relatively wealthy farmer, but it was the end of the Edo period (1603-1867), a turbulent period of Japanese history. At first, he tried to overthrow the edo shogunate, but changed his mind and became one of the top retainers to the shogunate, and showed his talent under the last shogun of Tokugawa Yoshinobu. He was also dispatched to France, where he brought back to Japan the advanced technology and social systems of the time and contributed to the modernization of Japan. As an official of the Ministry of Finance, he was able to contribute to the westernization of the national system due to his strong accounting skills.

Later, he became involved in the establishment of private companies based on the idea that the country could not develop without improving the lives of its people. In addition to the aforementioned companies, he was involved in the establishment of various industries such as Sapporo Beer, Asahi Beer, Oji Paper, Imperial Hotel, railroad companies, etc.

Publishing "Rongo to Soroban" (the Analects of Confucius and Arithmetic)

Although he wrote many books in his later years, "Rongo to Soroban" was published in 1916, when he was in his late 70s. So it is said to contain his life's philosophy and teachings. Shibusawa Eiichi lived through four eras: the Edo period (1603-1867), the Meiji period (1868-1912), the Taisho period (1912-1926), and the Showa period (1926-1989). What did he write about in this book?

This book consists of ten chapters, but the first three chapters are particularly important. We can learn a lot just by reading these three chapters.

1) Life and Beliefs (処世と信条 Shosei to Shinjo)

In this chapter, he says that the Dotoku (Analects of Confucius) and the Arithmetic, that is, morality and economics, are seemingly distant but very close. The reason for this is that wealth should be sustainable, not transient. Money that you happen to make by gambling for example is not real wealth. Real wealth is not sustainable unless it is in line with human reason and morality. This is because business is an economic activity that helps people become wholesome, and it is only possible when there is a connection between people. As long as there is no human connection at the root of wealth, the activity will not be sustainable. And the wealth of a country cannot be achieved without the development of its people. Therefore, morality and economy are very close to each other.

He also explains how to judge a person. Shibusawa advises us to look at a person from three perspectives.

- 視 Seeing… its appearance, form, action, and conduct

- 観 Watching… the spirit that motivates action.

- 察 Observing… What satisfies them? What makes them satisfied in their life?

First, look at the external appearance. Then, we can watch and learn about the mindset of the person that motivates the action. However, that motive may not be the true motive, so we need to dig deeper to find out what makes the person satisfied. These are the three perspectives from which we should judge a person, said Shibusawa.

For example, let's say there is a woman who is dieting. Her motive for dieting is to lose weight, but is she truly satisfied with that? She may be satisfied when she is being pampered by men, or when she is living a healthy life, or when she is able to stand out from her female rivals, or when she is satisfied with what she is doing because everyone else is doing it. In other words, what makes you satisfied is your true motivation. Knowing the true motivation of a person can reveal his or her true humanity.

He also advocates the crab-hole principle. It is said that a crab digs a hole the size of its shell and lives in it. The idea is that it is good to live a life that is appropriate to one's status. In other words, each person's abilities are different, and while you can develop your abilities with effort, what you want to do and what you are not suited for are different for each person. The idea is that you should contribute to society by doing what you are suited for and where you can develop your abilities. Eiichi Shibusawa was asked to be the head of the Bank of Japan, but he refused. This is the reason why he insisted on establishing a private company even after being asked to fill such an important post.

2) Rising aspirations and Learning (立志と学問 Risshi and Gakumon)

What is your mission in life? It seems like a simple question, but it is not easy to answer. In order to find the answer, we need to engage in various activities to assess ourselves. At the age of 33, Eiichi Shibusawa decided to pursue a career in business, and by the time he was 70, he realized that he had made the right decision. Originally from a farming family, he had dreamed of becoming a warrior of higher rank, but he became a government official and it was not until he was over 30 years old that he started his own private companies. It was not until he was over 30 years old that he began to work hard at establishing private companies, using his own abilities to develop Japan's economy. He believed that such great aspirations can be gradually realized by living hard in the present moment.

3) Common sense and Habit (常識と習慣 Jyoshiki to Shukan)

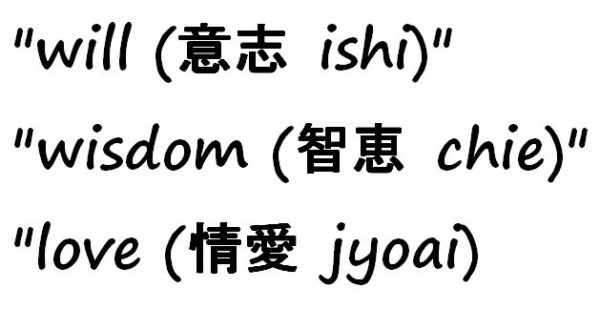

In this chapter, Shibusawa also mentions something very important. In order to be successful, the three elements of "will (意志 ishi)," "wisdom (智恵 chie)," and "love (情愛 jyoai)" are essential. It is necessary to have these three elements as common sense.

If you don't have the will to do something, you will not be able to do anything. In other words, you have to have the will to do something first. You have to have a purpose for what you want to do. Then, you need to exercise wisdom. In order to gain wisdom, you need to study and gain experience. This is how we can achieve our goals, but the third important factor is love. We need to share the fruits of our success. If you don't do this, you will not become a virtuous person. The people who have made a name for themselves in history have always had this "love."

You must not sacrifice anything for the sake of your own selfishness, because someone will surely see through it, and you will inevitably fall into a hole.

4) Humanity and Wealth (仁義と富貴 Jingi to Fuki)

No matter how hard you have worked to build your wealth, it is misguided to think that you have built it all by yourself. One cannot do anything on one's own. It is because of the state that we are able to carry out our economic activities safely. (Be minded that Shibusawa Eiichi went through various wars.) In that sense, the more wealth you have, the more you are supported by the society, and it is the natural duty of the wealthy or the rich to do volunteer work or relief work to repay the benefits to the society.

However, charity also requires caution. It should not be about giving large amounts of money to the poor. It should not be a small gesture or an activity to make oneself look good and respectable. It is important to contribute with the hope that the society will remain stable.

At the same time, for the rich and wealthy it is important not only to save money, but also to use it properly and consume it.

5) Ideals and superstitions (理想と迷信 Riso to Meishin)

Confucius was born in B.C., before Jesus Christ, and his teachings were later used as the basis for the Zhu Xi and Yang Ming schools. However, this is a misinterpretation and there is no need to reinterpret the teachings of Confucius if the essential human being is the same today as it was in the past.

6) Character and Cultivation (人格と修養 Jinkaku to Shuyo)

However, in order to develop one's character, it is necessary to keep the following points in mind. There is little difference between humans and animals. However, the value of a human being lies in whether or not he or she can make a useful contribution to the world. We need to pay attention to this when forming our character. Especially in Japan, there was no religious value system such as Christianity in that period, late 19th century. Therefore, it is necessary to have a code of conduct to become a person who can contribute to the world.

7) Arithmetic and Rights (算盤と権利 Soroban to Kenri)

First of all, saying that making money is a dirty thing is not true! And that's not what Confucius said either. Confucius didn't say that, but he did say that it's better to be poor than to earn money by doing dirty things. But he does say that if you make money the right way, it's okay. This is a very important part of human activity. If you have to win a game, you have to win it. The right thing to do is to win and then use the winnings for the benefit of everyone.

In other words, it is necessary to have both the strength to win the game and the kindness to share it afterwards.

8) Jitsugyo and Bushido (実業と士道 Jitsugyo to Shido)

Bushido is a complex morality that adds the virtues of justice, integrity, chivalry, bravery and courage, and politeness and humility. It is a shame that this noble morality was used only in samurai society, and that it should be used in commercial activities that pursue profit.

9) Education and friendship (教育と情誼 Kyoiku to Jyogi)

In addition to knowledge and learning, one must also have a high moral character and personality in order to win the respect of the disciples. A person who stands above others must acquire not only knowledge and learning, but also character and virtue. Shibusawa also said that filial piety should not be forced on children, and that the key to the development of the country is to utilize women and promote those who are capable.

10) Success/Failure and Destiny (成敗と運命 Seihai to Unmei)

Kusunoki Masanari was a failure in his lifetime, while Ashikaga Takauji was a success, but it is Masanari who is revered today. Sugawara no Michizane was driven away by Fujiwara no Tokihira, who was a successful man at that time, and Sugawara died in disappointment. However, he is still revered as Tenmangu Shrine located in many parts of Japan. In this way, it seems that success in the world is not necessarily success and failure is not necessarily failure. Only the history will judge later on.

There are many examples in the world of people who wanted to succeed but failed. Fate can be developed only when it is accompanied by wisdom. Therefore, no matter how good a person is, if he is lacking in wisdom, he will not be able to make the right decision when the time comes and success will be far away.

What would have happened if Toyotomi Hideyoshi had lived to the age of 80 and Tokugawa Ieyasu had died at the age of 60? The reigns of the Toyotomi family may have been over, but it is unlikely that Hideyoshi, who was not blessed with a brain as wise as Ieyasu, would have been able to create a world of peace and tranquility for nearly 300 years like the Tokugawa.

Shibusawa Eiichi thinks that Ieyasu was able to attract luck because he had wisdom and power.

Therefore, Eiichi thinks, if we do not say that our luck is bad, but think that we lack wisdom and continue to study, we will one day be blessed with good luck again and achieve success.

To those who study and work hard with sincerity, heaven will naturally guide them to develop their destiny.

What did you think? This is a book about the morality Shibusawa Eiichi strongly believes that is still relevant today and should be read not only by those in charge of management but also by employees. It's not just a business book, but also a book for life as well.

Related articles:

"Who is Shibusawa Eiichi?"

“A role mode employee at a Japanese company (learned from Shibusawa Eiichi)”

2 thoughts on “Understanding "Rongo to Soroban" in English by Eiichi Shibusawa”