The Man Who Saved the Country, Japan and the World

Masao Yoshida Who Defied Company Orders to Save Japan from Fukushima Nuclear Disaster

By Ryusho Kadota (journalist) and Soichiro Tahara (journalist)

Securement of a Line to Deliver Seawater Was Crucial

Tahara: Mr. Kadota, the book you wrote, “Shi no Fuchi wo Mita Otoko” (“The man who saw the abyss of death”, published by PHP Institute) is a very good read. After the incident at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, everyone in Japan thought Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) was evil personified. But after reading your book, I realized that Masao Yoshida (then plant manager) and the people working under him at the Fukushima Daiichi site really risked their lives to get the incident under control. I found that moving because that side of the incident didn’t get reported at all. When did you start gathering material for it?

Kadota: It was immediately after the incident occurred on March 11, 2011. Everything depended on whether I could get an interview with Yoshida, who was plant manager at Fukushima Daiichi at the time of the incident. You could even say that my activities over the next year and a few months were all in order to persuade him. I thought that if I could get the OK for an interview with Yoshida, who was the “boss” so to speak of Fukushima Daiichi, on that basis, it would be easier to get permission in one go from all the people who fought at the site as well.

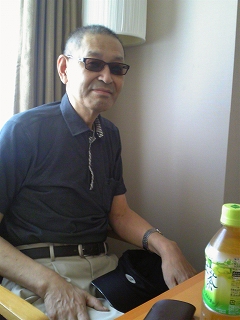

Tahara: You interviewed Yoshida in July last year. That was after he’d been operated on for esophagus cancer and completed his anticancer drug therapy – during the interval before he collapsed with a brain hemorrhage. Does that mean you got the actual approval from him a good while prior to that?

Kadota: No, that wasn’t the case. I got the OK for the interview with Yoshida while he was still undergoing anticancer drug therapy. That was in May 2012.

Tahara: So it was after his cancer had already been discovered – and the interviews with the technicians at the site took place after that, I assume. It wasn’t the case that you only started interviewing after obtaining permission from the TEPCO public relations department, was it?

Kadota: I think TEPCO’s public relations department was also troubled by the fact that a freelancer like me had acted on his own and managed to persuade Yoshida. Yoshida was also a TEPCO executive officer. Once someone in that position had given the OK, they couldn’t really put a stop to the interviews.

Tahara: What surprised me above all else when reading the book was that it uses the actual names of the parties involved. I don’t suppose that would have been possible had the interviews been done via the TEPCO public relations department.

Kadota: I checked directly with each and every one of the people who had assented to be interviewed whether I could use their real name. I did this afterwards, so I don’t think that TEPCO public relations knew that the book would use real names until it came out.

Tahara: I’d like to look back at the events on the day of the incident. When the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, the effects of the earthquake cut the electricity. Under normal circumstances, the system was that in-house power generators would cut in and cool the reactors. However, the diesel generators that this system relied upon were taken off-line by the tsunami, and by 15:41, the plant was in a position of having lost all electricity. As the coolant water for the reactor cores could no longer be cooled, the nuclear fuel started to burn rapidly. If left in this state, there was a risk that the reactor containment vessels would explode. That was the situation. What did the people at the site decide they should do?

Kadota: Both Yoshida, who was in the emergency operations room inside the quake-proof master building, and the plant engineers in the central control room concluded that “The only thing to do is use Pacific seawater” at virtually the same time. In other words, they decided that all they could do to cool the reactors was to pump seawater into them. In order to do that, they had to construct a line (pipe) to get the seawater into the reactors. By reworking the fire extinguishing line that ran water to the inside of the reactor buildings, they were able to get water to the reactor core. It was do-or-die work performed in total darkness using flashlights.

Tahara: Radiation levels in the surrounding area had already gone up, so there must have been a risk to their physical safety. How did they feel about that?

Kadota: It seems they were considerably fearful of it, as you might expect. It was very hot inside the reactor buildings and white particles were floating about amid the pitch darkness. When the plant workers at that time were asked whether those particles were radioactive, they answered, “We didn’t really know.” They worked in those conditions for several hours, trying to read out the numbers on valves.

From 11:00pm that day, going inside the reactor buildings themselves was banned by plant manager Yoshida as radiation levels had gotten high. Subsequently, the securement of a line to deliver seawater – a decision made there and then at the site – would later prove to be massively important. Had they not done that, cooling the reactor cores would have already been impossible.

No Room to Even Think About One’s Family

Tahara: To continue, I’d like to ask you about the vent problem. To prevent the containment vessels from exploding, the pressure inside the reactors had to be released outside. That’s where the vents come in. According to your book, plant manager Yoshida gave the order to ready the vents at the site (unit 1) around midnight, i.e. the start of the next day, March 12. However, Yoshida himself had already ordered that the reactor buildings were off-limits. So the act of getting to the vents also involved staring death in the face. To be frank, I think you could even call it a suicide mission.

Kadota: Certainly, and I think Yoshida was also deeply distressed by the fact that the entry team was being asked to walk the fine line between life and death. The man at the site who bore responsibility for deciding the personnel for that mission was Isao Izawa, who was the main control room’s shift supervisor for units 1 and 2. Apparently, the first thing Izawa said was, “I’m terribly sorry, but I can’t send in any young people.” The younger staff still had a future in which to have children, so Izawa picked older veterans as the main entry team members.

There was a moment of deathly hush before Izawa himself broke the silence. With the situation worsening, Izawa had already dispatched his workers to dangerous places such as the reactor buildings time and time again. He felt terrible about that, and apparently wanted to go on this final mission himself. Doing so would also assuage his guilt, he said. However, two shift supervisors senior to Izawa stopped him, telling him, “You stay here.”

Tahara: One after another, the younger workers then also volunteered for the job, didn’t they?

Kadota: Yes, they did. Izawa was nearly in tears when he told how the younger workers started to call out from the gloom: “I’ll do it.” “I’ll go too.”

Tahara: Around that time, (former) Prime Minister Naoto Kan visited Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. He flew in by helicopter on March 12 and yelled, “Why haven’t you opened the vents?” That must have been annoying for the staff at the site.

Kadota: Very much so, because actually opening the vents would simultaneously release radioactive material. Since it hadn’t been confirmed whether the local residents had managed to evacuate yet, the fact that the go-ahead hadn’t been given to enter the reactor buildings and open the vents was hardly surprising.

With radiation scattered around, Yoshida found himself needing to source some appropriate protective equipment for the prime minister’s party that was to visit the plant. However, as there was no leeway to handle this at the site, Yoshida held a video conference with the headquarters and asked them to prepare some equipment, but was told, “Deal with it on site.” This infuriated Yoshida. “You can’t be serious!” he replied, and the two parties had a huge argument. Yoshida clashed with the headquarters over each and every thing, but had he been the type who was subservient to the headquarters, it is unlikely that the workers at the site would have trusted him as much as they did. Having repeated arguments with the headquarters was also needed to capture hearts and minds on site.

Tahara: I see. So in the end, did the headquarters provide the equipment for the prime minister’s party?

Kadota: No. There was no equipment whatsoever, so the prime minister’s party went into the quake-proof master building where plant manager Yoshida was. Put simply, they did not seem aware that they may also have been exposed to radiation.

Tahara: The presence of Naoto Kan was nothing but a hindrance for the people at the site. However, after reading your book, I started to understand why Kan acted the way he did at the time. The information available was so tangled that no proper reports were getting through to the prime minister. In those circumstances, I can understand why he would feel like wanting to check for himself.

Kadota: Quite so. The greatest mistake made was shutting away experts like Haruki Madarame, chairman of the Atomic Safety Committee, in a small room on the second floor of the crisis management center inside the prime minister’s office. From there, the only means of communicating or gathering information were two fixed-line telephones. In other words, an expert had been placed in an “information isolation zone.”

Tahara: Yoshida gave the go-ahead to open the vents at the site after Kan’s party had left, didn’t he? Around what time was that?

Kadota: It was nine o’clock on the morning of the 12th. How on earth must they have felt when the time came to enter the reactors? When I spoke to some of the members chosen for the entry team to find out, asking, “Did you think about your wife and children?” I got the reply, “There was no scope to think about that.”

Apparently, in the time before going in, the members repeated visualization exercises, confirming details amongst themselves such as “So we go up this ladder, then head to the right, or to the left?” while trying to form images in their minds of the inside of the reactor buildings. The challenge for them was whether they could turn the valve handles or not before dying.

Tahara: They could not afford to die before opening the vents.

Kadota: Because if they had failed, it literally would have been the end for Japan. That’s precisely why, like how the entry team members answered, they didn’t even have room to think about their families.

“We Were Prepared to Die Together”

Tahara: After opening the vents, pouring in seawater was the next problem at the time of the incident. While they were still deliberating at the prime minister’s office whether to inject seawater or not, Yoshida had already started doing it.

Kadota: The reason why the prime minister’s office gave the order to cease injecting seawater was allegedly because Madarame, the committee chairman, said that “replacing the coolant with seawater could potentially cause re-criticality.” However, that isn’t the case, and when I checked that with Madarame himself, he denied it and maintained that he had said, from an early stage, that “the only thing to do is inject seawater.” When he was asked at the time whether there was any possibility of re-criticality (re-critical state) from injecting seawater, Madarame had answered, “The possibility isn’t zero,” and this comment became misunderstood.

Tahara: By re-criticality, you mean that a chain nuclear fission reaction starts again in nuclear fuel that had been shut down (in a pre-critical state).

Kadota: Yes, and Madarame’s answer that the possibility of this “isn’t zero” was a scientist-like response. But Banri Kaieda, former Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano sensed a clear and present danger, and their mistaken perception spread throughout the prime minister’s office. Hearing that, Prime Minister Kan ordered a review into whether re-criticality was possible from injecting seawater.

Tahara: So as Kan only said, “Review it” rather than “Stop it” regarding injecting seawater, he evaded responsibility. However, Kan must have had some other expert staff around him in addition to just Madarame. I’ve met up with Ichiro Takekuro, who holds the executive level title of “fellow” at TEPCO, a number of times since the incident. What role did he play at the time?

Kadota: Actually it was Takekuro who called Yoshida to get him to stop injecting seawater. “Just stop it,” he said. He asked Yoshida very forcefully, it seems, right down to his way of speaking. “Shut up. I’ve got the prime minister’s office on my back!” Takekuro said. “What are you saying?!” Yoshida retorted. It was a fierce exchange. Subsequently, after Takekuro had abruptly hung up the phone, Yoshida was expecting a call from TEPCO the headquarters giving him the official order to stop injecting seawater, so he started to take measures in advance. He gave detailed instructions to the relevant persons in charge: “When the order to stop injecting seawater comes, I will give you an order to stop clear enough to be seen in a video conference with the headquarters. But it is purely a meeting-related matter. At the site, make sure the seawater injection continues.”

Tahara: So he rejected the order from the headquarters?

Kadota: Right. I think Yoshida was the kind of man who never forgot the fundamental principles, whatever the situation. As a power supplier – a nuclear power supplier – the primary objective and fundamental principle is to protect the lives of the people. Yoshida was acting with that in mind.

Tahara: That poses a question. Neither Kan nor Edano could judge whether to continue injecting seawater or stop it, which couldn’t be entirely helped as they weren’t nuclear experts. However, that wasn’t the case for the management elites crammed into TEPCO’s the headquarters. Why did they give foolish orders such as “stop injecting seawater”?

Kadota: The TEPCO executives were people who attached more importance to directives from the prime minister’s office than to what they ought to do as a power supplier. In short, they were people without fundamental principles. Indeed, that type of behavior is probably all-too-common among management elites.

Tahara: But Yoshida himself was an executive officer, wasn’t he. Surely he was also one of the elite. Why was Yoshida the only one who could defy company orders and stick to his fundamental principles? I think that’s the most important point.

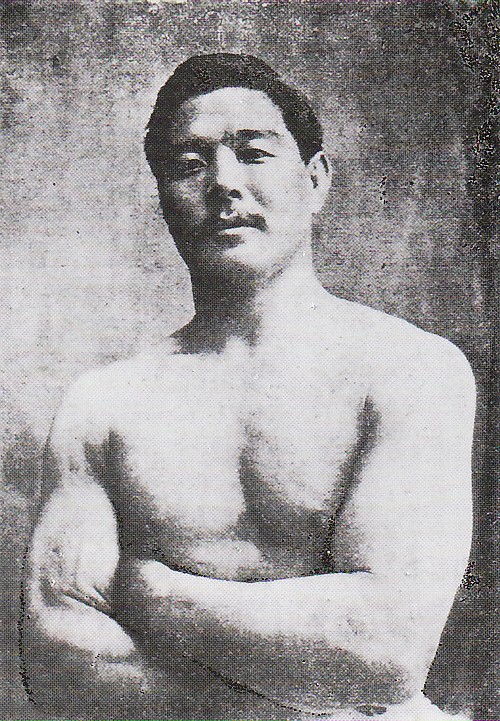

Kadota: For people, it is times of crisis that call into question the way we live. Wanting to know what kind of person Yoshida was, and also to indirectly persuade him to be interviewed, I visited his friends from his junior high and high school days. Yoshida was born in 1955 while I was born in 1958, so you could say we’re from the same generation, but to be frank, I think he was the kind of man who was incomparable in this day and age.

Tahara: What kind of man was he?

Kadota: Like Kensaku Morita, the actor and singer-turned-prefectural governor of Chiba Prefecture, from his junior high and high school days, it seems Yoshida was the type who would earnestly ask his friends, “How are you going to get on in life living like that?” At the same time, he had a very strong interest in matters such as life and death, religion and philosophy. All of his friends unanimously said that he had been a leader from way back. His wife also told me, “My husband had always been a pious man.” Even when dating in their younger days, when they went on a trip, time and time again Yoshida – who liked touring around temples and shrines – would apparently ask the chief priest to show him the Buddhist images that weren’t usually on display to the public. From his younger days, Yoshida read a wide range of religious texts, and his desk-side book was “Shobogenzo” (“Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma”) by 13th century Zen Buddhism teacher Dogen. He even kept a copy of it in the Fukushima plant quake-proof master building.

I asked the workers who fought under Yoshida at the time of the incident how it would have played out if Yoshida hadn’t been plant manager of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant at the time. With that, all of them answered, “Without Yoshida, we would have been lost,” or “With Yoshida as plant manager, we were prepared to die together.”

Tahara: Why did his workers trust him so much?

Kadota: That’s because Yoshida himself always trusted his workers. That attitude of mutual trust could also be seen in their behavior at the time of the incident. Apparently, when the workers returned to the plant for the perilous task of getting the situation under control, Yoshida shook each worker’s hand, one-by-one, and said, “I appreciate you coming back,” and thanked them for their efforts. Plus, as I mentioned earlier, he didn’t give up any ground in the face of unreasonable requests from the headquarters. Putting the mental states of Yoshida and his workers at the time of the incident into words is difficult, but there’s no question that both parties had a firm trusting relationship that allowed them think, “I’d be prepared to die with his person.”

The Stress of the Nation Standing at the “Abyss of Death”

In the afternoon of Saturday, March 12, an explosion occurred in the building housing Reactor 1, caused by the ignition of the hydrogen. The upper part of the building was destroyed. Monday around 11am, March 14, a similar explosion occurred in the Reactor 3 building, blowing off the roof. Finally, early morning on Tuesday the 15, an explosion took place in the Reactor 2 building. Part of the Reactor 4 building was damaged.

After the explosion on March 15, 2011 (Left building houses Reactor 3 and the center one houses Reactor 4.)

Tahara: I’d like to continue talking a little more about the time of the incident. Sometime after 5:30 on the morning of March 15, there was a scene at TEPCO the headquarters when Prime Minister Kan stormed in shouting, “There’s no way you can pull out!” Via video conferencing, those circumstances were seen by the people at Fukushima Daiichi, including Plant Manager Yoshida. What did you think about Kan’s behavior at that time?

Kadota: Firstly, I think there was a problem with the words used by Masataka Shimizu, who was TEPCO president and chief executive officer at the time. He said in a phone call to government ministers Kaieda and Edano, “Unit 2 is in a very grave situation. We’re considering pulling out should conditions get progressively worse.” He ought to have added the words, “However, personnel necessary for maintaining control will be exempt from the withdrawal” at the end of the statement. However, as he didn’t, the statement was reported to Prime Minister Kan as “We’re pulling everyone out.”

Tahara: After that, Prime Minister Kan summoned President Shimizu from TEPCO the headquarters to the prime minister’s office and grilled him directly about the withdrawal, didn’t he. Shimizu answered plainly that “We’re not thinking about pulling out,” so why didn’t Kan take that on board?

Kadota: By that time, Prime Minister Kan had already completely stopped believing what TEPCO was saying. I think he probably decided to march into TEPCO the headquarters when he heard reports of “withdrawal” from ministers Kaieda and Edano.

Tahara: Meanwhile, Yoshida and the plant workers battling at the site had no intention of withdrawing. How did they perceive the agitated figure of Prime Minister Kan?

Kadota: Later, after carefully watching the images that were made public, there was a scene where Yoshida, sitting in the director’s chair in the middle of the conference round table, turned his back on the video conference camera and stood up to tuck in the hem of his shirt. He maybe wanted to bare his bottom to the prime minister and say, “You idiots!” I say “maybe” because when I spoke to Yoshida himself about what he was doing at that time he didn’t remember anything about it. From right after the earthquake occurred, Yoshida had been directing proceedings without sleeping or taking a break. As a result, he lost a considerable part of his memories of that time.

Tahara: Around how many days did Yoshida stay awake?

Kadota: After the earthquake occurred on March 11, Yoshida stayed in the director’s chair in the quake-proof master building and didn’t sleep for the five days. He would have died if he hadn’t slept. What he did was reach an agreement with the headquarters that they wouldn’t contact each other for two hours or so unless there had been a change in the situation. Doing this allowed Yoshida to take brief naps, albeit just for an hour or 30 minutes.

Tahara: He did well to keep his spirits up.

Kadota: It must have been an extremely stressful situation. I called the book “The man who saw the abyss of death,” but it wasn’t just an abyss of death for Yoshida himself: he was standing at the abyss of death of the whole nation, so to speak. Every time a reactor was plunged into crisis, that stress cascaded over his body time and time again. That’s why I think Yoshida suffered from an illness that would be ultimately fatal.

What Would Have Happened Had It Not Been for Yoshida?

Tahara: Sadly, on July 9 this year, Yoshida passed away at the age of 58. On that occasion, newspapers and TV channels ran special features praising his deeds as Fukushima Daiichi plant manager. To round off our discussion, what do you think would have happened to Japan had it not been for Yoshida?

“10 times worse than Chernobyl”

Kadota: He said to me that the worst possible scenario would have been damage on a scale “10 times worse than Chernobyl.” Ten kilometers to the south of Fukushima Daiichi, which has six reactor units, is Fukushima Daini with four units, making 10 units in total. If controlling those 10 reactors hadn’t been possible – if the runaway reactions hadn’t been stopped – I think it would have formed a chain of calamities that really would have caused damage of that scale. Although we can’t simply compare Fukushima and Chernobyl, which involved a different type of reactor, from Yoshida’s words we can get a feel of the projected damage level that the people at the plant were fighting against.

When I spoke with Madarame about what Yoshida had said, he told me that if it hadn’t been possible to control Fukushima Daiichi and Daini, the Tokai Daini Nuclear Plant in Ibaraki Prefecture would have also been affected in addition to Fukushima. The resulting radiation fallout would have made eastern Japan uninhabitable. Japan would have been separated by three areas: uninhabitable eastern Japan, Hokkaido and western Japan. The fact that it didn’t turn out that way is, I think, the result of the struggles of Yoshida and all the people who risked their lives at the site. The late Masao Yoshida: the man who miraculously saved Japan. May you rest in peace.

Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Decommissioning Project Study Facility

One thought on “The Man Who Saved the Country, Japan and the World”