Exploring the Source of Motenashi, Japanese-style Hospitality

CONTENTS

Exploring the Source of Motenashi, Japanese-style Hospitality

Why do Uniqlo’s services captivate people around the world?

Japanese-style services are now drawing envious stares from many countries. Despite the fact that there are cultures of hospitality all over the world, why does only the Japanese one attract people’s attention? How different is Japanese hospitality from that in Europe and America? This article probes its originality by tracing the history up to ancient times.

Omi Merchants’ Precepts for Business

There has been an active movement to drastically re-examine and reform the current commercial services using motenashi in Japanese or hospitality in English as a keyword. Only Japan and Western Europe have the experience of a highly developed feudal society, and the business culture that blossomed during the feudal age set the direction of customer business in their modern societies. It can be said that the above-mentioned movement is also a movement to get back to the starting point and revitalize their original commercial services.

As a preeminent manufacturing power, Japan possesses world-leading power in various industries. Everybody knows this. At the same time, however, we must not forget that Japan was the world’s most advanced nation also in commerce. In fact, Japan had already formed a unified, nationwide market in medieval times. In early modern times, mass consumer markets were created in major cities such as Edo (present-day Tokyo) and Osaka. Because the castle towns across the country had a large nonproductive population, the most important business theme was to promote daily-use consumer products. Edo became a city of one million people in 1721. Around the same time, London had a population of 700,000 while Paris had a population of 500,000. Thus, Edo was the largest city in the world at that time.

For this reason, Japan arranged commercial services targeted at the general public at an early stage, which was different from other countries. And the core of the services was “motenashi.” The merchants in the Omi region in the early modern ages are known to have conducted business of all kinds using a nationwide network. The Precepts for Business written by these Omi merchants have the following precepts regarding the motenashi for customers:

- Business is a service for people and the world. Profits are rewards for the service.

- Not compliments before selling, but services after selling make for long-standing customers.

- You need not worry about your insufficient funds. You should worry about your insufficient credit.

- Do not sell by force nor sell what the customer likes. Sell what benefits the customer.

- A free gift always pleases customers even if it’s a piece of paper. If you have nothing, give them your smile as a free gift.

This unique Japanese spirit of motenashi (or omotenashi) described in these precepts was shared by wide ranging service businesses, from hot spring inns and kimono dealers down to small-town retailers. It is true that there are customs and cultures of hospitality in all societies in the world. But Japan is the only nation that developed and enrooted the culture of hospitality that targeted not only the upper class people but also the ordinary people. Then, all through the modern ages, Japan continued to pursue how to treat and entertain customers, how to soothe their mind and body, and how to respond to requests from the community.

Amid the recent globalization of the economy, however, the efficiency of services has been promoted and the service procedures have been compiled into manuals. As a result, customers have had no choice but to yield themselves to one-sided services and systems that are much different from soothing of the mind. This strange situation as if the cart were put before the horse has become a global phenomenon. Even in Japan, the traditional motenashi spirit has been diluted in no small measure.

The Difference From the Western Hospitality

Traditionally, the commercial hospitality in Europe and America has been offered only as preferential services for the aristocracy or upper class people. Probably because of this, in Europe and America, the recent movement to review hospitality has been limited to international, exclusive hotels and upscale clothing stores. The hospitality of restaurants and retailers targeting ordinary people has remained low without any change. In China, Korea and other Asian countries, in addition, the hospitality of their service industries has remained to be superficial or a mere formality though it has been improved under the influence of Japan and the Western countries.

Nevertheless, there is a noticeable change these days. In the commercial districts in Europe, America, China and Korea, the Japanese-style hospitality “motenashi” is now attracting a lot of attention. An example is the case of Yaohan, a department store that branched out and took root in Shanghai in 1995. Among the several dozens of department stores in Shanghai, Yaohan has maintained its top position in terms of sales and profit rate for several years. It is interesting that, although Yaohan came under Chinese control due to Chinese funding after its bankruptcy, the management policies were kept unchanged. Yaohan is still thorough about providing Japanese-style services and Japanese-style product assortment as well as Japanese-style employee training.

The latest example is the case of Uniqlo, a fashion retailer that caters to the common people. When you visit the Uniqlo store in Paris, its Parisian salesclerks greet you in their bright voices all together. The inside of the store has been cleaned up thoroughly and is kept immaculately clean. The shirts are neatly folded and beautifully stacked with a consideration to their colors. The display racks are arranged so as not to block the customers’ views, by taking into consideration the average heights of customers from various countries. For these meticulous, Japanese-style services, Uniqlo in Paris has been enjoying a great reputation. This applies also to the Uniqlo stores in New York, London and Shanghai. In any country other than Japan, there has never been a store that offers such high-quality services to the common people. You might say this is a whole new ball game.

Until two or three years ago, no one would have imagined this situation. Also in China and Korea, the poor customer services that have been criticized saying “which is a customer, you or me?” are rapidly vanishing. Instead, the fine and attentive Japanese-style motenashi services are introduced in a positive manner.

Why now are the countries around the world trying to adopt the Japanese-style motenashi services? One thing that can be said is that the custom and spirit of cordially welcoming guests from distant places as if they were gods is a tradition of not only Japan but also every other society in the world. In many countries, however, there has seldom or never been a movement to make use of this traditional hospitality in business in the mass consumer market. Perhaps, it is fair to say that the global phenomenon of returning to good old tradition is occurring also in the service industry.

Origin of “Host” and “Guest”

Originally, motenashi or hospitality has its roots in a custom where the people inside a community welcomed those from outside the community as their guests and offered them lodging and meals in order to achieve a close relationship with them. Thus, hospitality was not given to the people in the same community. Inside the community, the members dined together and shared food to enhance the relationship among them.

In each community, the people made offerings for gods at festivals. The offerings were not only for the gods but also to be shared by the gods and the people. Thus, the people had meals together with the gods. This is called “shin jin kyosyoku (food-sharing between gods and people),” or a communion. The offerings as the means of communicating with the gods were considered as auspicious food, and used also as the means of facilitating communications among the people. This food-sharing performed inside the community was then extended to welcome people from outside the community. This was the start of hospitality and services for guests.

About the folkways of food sharing, Kunio Yanagita who is known as the founder of Japanese folklore said as follows:

It seems that people shared auspicious food not only with their family members but also with the people around them whom they rely on in their daily lives in order to establish an invisible chain relationship with them. In essence, it had the same intent as that of our practice in which we invite the people around us on the occasion of a family event such as a wedding or birth of a baby, and share various homemade dishes with those guests. This relationship is called “morai (receiving)” in Japanese. (“Food and the Heart”)

Thus, the people inside a community had meals together and established a close morai relationship in which they received favor from (shared food with) one another. The people then welcomed visitors from outside the community as guests having come from distant, foreign lands, and entertained them with their local auspicious food aiming to achieve a close relationship with them.

Even today, we have the custom of having meals together with friends or by inviting people that we don’t know well with the aim of building closer ties with them. This custom originates in the ancient belief that, by practicing “shin jin kyosyoku” in which the members of a community welcomed the gods and shared food with the gods as well as among themselves, they would be able to become united, be born into a new life, and acquire new energy.

Kunio Yanagita thus described the significance of “shin jin kyosyoku.” The point was to have meals together, and by doing so, the people could share their joy and make friends with other people. That was the original purpose of motenashi.

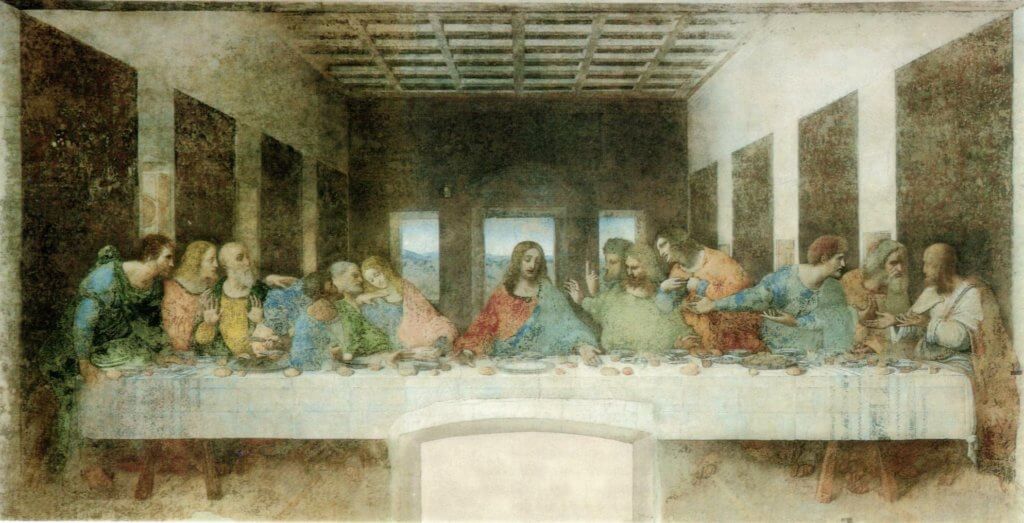

It is said that, at the Last Supper, Jesus Christ took bread and a cup of wine and told his disciples, “This is my body and this is my blood.” In commemoration of this, bread and wine are given to people at Christian communion services.

Dinner parties held in Christian communities have such a background as this. Perhaps this can also be called a type of “shin jin kyosyoku.” The bread and wine are called the Host. Both terms “host” and “guest” in English are related terms of “hospitality” and all of them have their origins in Latin.

Spiritual Home Where the Tea Ceremony Takes Us

In Japan, against the backdrop of the above-mentioned traditional custom of welcoming visitors as precious guests, motenashi was exercised in various forms in every social class. In the societies of the samurai and court nobles, a formal style of motenashi, in which the host invited guests for a banquet, served food and wine, and gave them a gift as a token of appreciation for their visit, was established at an early stage. The people then learned the relevant manners and accumulated proficiency at them to develop the culture of motenashi as a part of their high-society culture.

Meanwhile, in medieval manors and duchies, the local officials and farmers were obliged to entertain the governors who would come from the capital city. This became an opportunity for the lower class people to learn the style and manners of motenashi being exercised by the upper class people. In and after the Muromachi period (1338 to 1573), in addition, the feudal lords and local magnates in towns and villages came to interact with each other socially and culturally. With the advancement of the urban culture, the practice of motenashi by samurais and court nobles gradually spread to ordinary townspeople and village people. In the late Edo period (1603 to 1867), the culture developed by urban rich people, which includes the flower arrangement, tea ceremony, and calligraphic works and paintings, spread to rural, mountain, and seaside villages. Then, in due course of time, a national culture of motenashi was formed beyond the social classes and positions.

Japan is the only country that produced a national culture in a society that had a class system. It was enabled through vigorous exchanges and fusion between the upper class culture and lower class culture. As typified by the flower arrangement and tea ceremony that were developed in and after the Muromachi period, a culture widely shared by the people of all social classes was established. Against this backdrop, the Japanese-style motenashi in commercial services that targeted not only the upper-class people but also the ordinary people was developed.

In particular, the culture of the tea ceremony in which the host and guests enjoy their meeting together played an important role. As we all know, the tea ceremony is deeply related to wide ranging cultural factors from calligraphic works and paintings, craftwork, architecture, gardening, flower arrangement, performing art and cooking to religion, ideology and literature. Nevertheless, the tea ceremony does not intend to create a gorgeous world by drawing on all of these cultural factors. Rather, it thoroughly cuts out excess beauty to create a simple and severe setting and quiet and calm atmosphere.

By doing this, the tea ceremony aims to share the experience of spiritual transcendence from the ordinary world and play in a fictional world beyond reality. The host takes the guests out of their everyday lives and leads them to another world to share the experience of a transcendental time and space. This is the core of motenashi in the tea ceremony.

In the tea ceremony, the ancient custom of “shin jin kyosyoku” performed to welcome gods visiting villages has been brought back in the form of sophisticated beauty. The garden adjacent to the tea house reproduces the scenery of deep mountains and the tea house is created in the image of a humble hut built in the mountain or by the sea. The people of rural, mountain, or seaside villages welcomed exiled Susanoo and people on a pilgrimage and entertained them as much as possible however poor they might have been. Thus the original images of motenashi are well preserved in the world of tea ceremony.

This is why the tea ceremony gives people a spiritual experience of returning to the home in their heart. The people then find themselves imagining this spiritual home as a utopia where they can truly be relieved and feel safe. In addition, the people intuit that this spiritual home is also the source of Japanese aesthetic values such as “wabi,” “sabi,” and “mono no aware.”

Aside from the tea ceremony, there are a lot of features that give the feeling of a spiritual home in many aspects of the Japanese motenashi culture. These features are what the service industries of other countries are gazing enviously at and trying to adopt. I think this movement symbolically indicates that a major trend is now being created on a global scale where the people who are exhausted from divisive competition are strengthening their desire for closeness with others and harmony with nature and seeking in them healing of their mind.